Kevin M.F. Platt is professor of Russian and East European Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and writes on Russian culture and history.

We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you're studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that's how things will sort out. We’re history's actors … and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.

—Karl Rove, quoted in Ron Suskind, “Faith, Certainty and the Presidency of George W. Bush,” The New York Times Magazine, October 17, 2004.

Susan Sontag: … I think in New York your aesthetic sense is, in a curious, very modern way, more developed than anywhere else. If you are experiencing things morally one is in a state of continual indignation, and horror but [they laugh] if one has a very modern kind of —

Philip Johnson: Do you suppose that will change the sense of morals, the fact that we can’t use morals as a means of judging this city because we couldn’t stand it? And that we’re changing our whole moral system to suit the fact we’re living in a ridiculous way?

SS: Well I think we are learning the limitations of the moral experience of things. I think it’s possible to be aesthetic…

PJ: … I mean your moral approach is the [Lewis] Mumford one that you’re speaking about.

SS: Yes.

PJ: Patrick Geddes, the greatest good, and we must be good and do these things. That criterion leads you into what we have today, so we’ve retreated, or maybe advanced, our generation — if I can lift you up.

SS: Oh it’s nice of you [they laugh].

PJ: To merely, to enjoy things as they are — we see entirely different beauty from what Mumford could possibly see.

SS: Well, I think, I see for myself that I just now see things in a kind of split-level way… both morally and…

PJ: What good does it do you to believe in good things?

SS: Because I…

PJ: It’s feudal and futile. I think it much better to be nihilistic and forget it all. I mean, I know I’m attacked by my moral friends, er, but really don’t they shake themselves up over nothing?

—From an interview for the BBC of Philip Johnson by Susan Sontag in 1966. Cited in Charles Jencks, Modern Movements in Architecture (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Anchor Press, 1973), 208-10.

A year and a half into Trump’s ascendancy and seventeen and a half years into Putin’s, it has become a commonplace in public and academic discussions to link their names to the term “postmodernism”—so much so that to provide anything like a full list of citations of such linkages is impossible. Discussions of Trump and Putin as “Postmodern politicians” come in many different forms and degrees of sophistication. My own modest contribution is intended only to dispel a bit of confusion that afflicts many in these discussions: “postmodern” politicians are not the “result” of “postmodernist theories” or of a “postmodern movement.” Such an idea fundamentally misconstrues both postmodernism and our current political and cultural situation.

Peter Pomerantsev has been a prominent member of these discussions since publishing Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: The Surreal Heart of the New Russia (2015), which described Putin’s Russia as a “postmodern dictatorship that uses the language and institutions of democratic capitalism for authoritarian ends.” Pomerantsev went on to detail the operations of Russia’s state-dominated mediaverse and the work of people like Putin’s long-time advisor Vladislav Surkov, who “has directed Russian society like one great reality show.” In a 2016 article in Granta, he turned his analysis toward American reality TV stars, claiming that, just like Putin, Trump’s “equaling out of truth and falsehood is both informed by and takes advantage of an all-permeating late post-modernism and relativism, which has trickled down over the past thirty years from academia to the media and then everywhere else.” As he explained, “Post-modernism first positioned itself as emancipatory” but has now brought about “an anarchic liberation from coherence.”

Shortly after Trump’s inauguration, David Ernst wrote in the Federalist that Trump’s triumph was caused by “the postmodernism that has long ascended to the heights of our culture: the nihilism in the common presumption that all truth is relative, morality is subjective, and therefore all of our individually preferred ‘narratives’ that give our lives meaning are equally true and worthy of validation.” "Postmodernism," he explained, is "the source” of various contemporary evils, from the emphasis of our culture on authenticity to political correctness. The discussion continues to resurface in articles such as Thomas B. Edsall’s New York Times opinion column on the anniversary of Trump’s inauguration, where the author investigated whether the President was "a Stealth Postmodernist" or "Just a Liar.”

In broader perspective, excoriation of postmodernism as the “source” of Trump and Putin is only the most prominent current expression of a longstanding tendency to blame postmodernism for all sorts of social ills—a mode of criticism that carried forward the anti-academic discourse of the 1990s culture wars and that still generates countless opinion columns in conservative news outlets. Ironically, controversial conservative thinkers in the Trump camp such as Jordan Peterson have recently retooled this conservative strain of critique in their battle against “postmodern Marxism.”

In a more academic vein, Mark Lipovetsky, the leading expert on Russian postmodernist literature, recently published a defense of postmodernist art and thought in the age of Putin and Trump in the New Literary Observer. In response to the common refrain that postmodernism is to blame for Russian neo-imperial patriotism, triumphal Trumpism, and post-truth politics in general, Lipovetsky demonstrates that even if the latter borrow from the former, they do so in a cynical and dull-witted way that has little to do with postmodern art or criticism. (This essay is derived from my response to Lipovetsky’s article, also published by the New Literary Observer.)

I am sympathetic to Lipovetsky’s position: Trump, Putin, Surkov (who also writes arch, “po-mo” novels and plays), and Karl Rove can hardly be compared in sophistication or in ethical sensitivity to classic postmodern authors like Don Delillo or Victor Pelevin.

But that, to my mind, is beside the point. Both assaults on postmodernism as the root of all evils, like Pomerantsev’s or Ernst’s, and defenses of it, like Lipovetsky’s, share a root misconception. Both put the philosophical cart before the sociohistorical horse by conceiving of postmodernism as the brand name of a philosophical and moral stance, championed by a “movement” of cultural figures and critical theorists, from Francois Lyotard and Fredric Jameson to Delillo, David Foster Wallace and Pelevin. In the terms of this debate, either these postmodernists—with their art, philosophy and control of the cultural heights and the universities—caused Putin and Trump, or they didn’t.

Ernst begins his essay with the proposition that “politics is downstream of culture,” a notion borrowed from Andrew Breitbart, who most likely coined it in the early 2000s. Organized in this way, such discussions grant improbable social authority to art, literature and critical theory. At base, this is a conspiratorial or Faustian model of history and society, in which a cabal of misguided, unhinged artists and philosophers, intentionally or unwittingly, released the evil spirit of postmodernism into the world, where it now wreaks havoc.

In reality, postmodern politics is not a symptom of postmodernism, conceived as a cultural style or philosophical position. Rather, it is a symptom of the era of postmodernity. And so are postmodern art, literature and theory. Maybe, then, we should conclude that the postmodern era caused Putin and Trump? Actually: no. Postmodernity and its political and aesthetic symptoms are all of a piece. Talk of a movement or to debate as to “what caused what” makes little sense, for no single cause invented or promulgated postmodernity.

As is the case with other comparable period terms (renaissance, romanticism, modernity…), postmodernity is a matrix of human action and reflection that arose in unison and that passes through loosely demarcated historical and local transformations. Postmodernity is, as Lyotard described it, a “condition” that we have fallen into, not a political or aesthetic program. In Jameson’s account, postmodernity is a stage of social and cultural development related to the triumph of consumer capitalism, advertising and spectacle, the increasing priority of the representation over things represented, the loss of ideological coordinates and the abandonment of any concept of the “forward march of history,” the ever-increasing fragmentation of the media world, and the ever-increasing integration of the economic one in a single market. Postmodern art, literature and theory are critical and creative responses to this social, economic and media condition that “expresses the inner truth of [the] social order of late capitalism.” Political practices such as those associated with the management of media and political rhetoric under Putin and Trump are also responses to this social condition—responses that cynically capitalize on the specificities of postmodernity in order to accumulate and retain power and wealth.

Spin doctors like Rove and Surkov (“political technologists,” to use the Russian term of art) may draw on the critical insights of postmodern literature and theory to accomplish their ends, but their political practices are not caused by postmodernist art and theory. And although Surkov’s reliance on such thinkers might enable a certain rise in subtlety in his manipulation of political life, it is more important to realize that postmodernist art, literature and theory cuts both ways. For it is theorists like Lyotard and Jameson and authors like Delillo and Pelevin who give us the best tools for critique of postmodern authoritarian regimes. Without postmodernist critical theory and literature, we would still have Trump (who unlike Surkov has no idea who Jameson is), but we would be even more fully at his mercy.

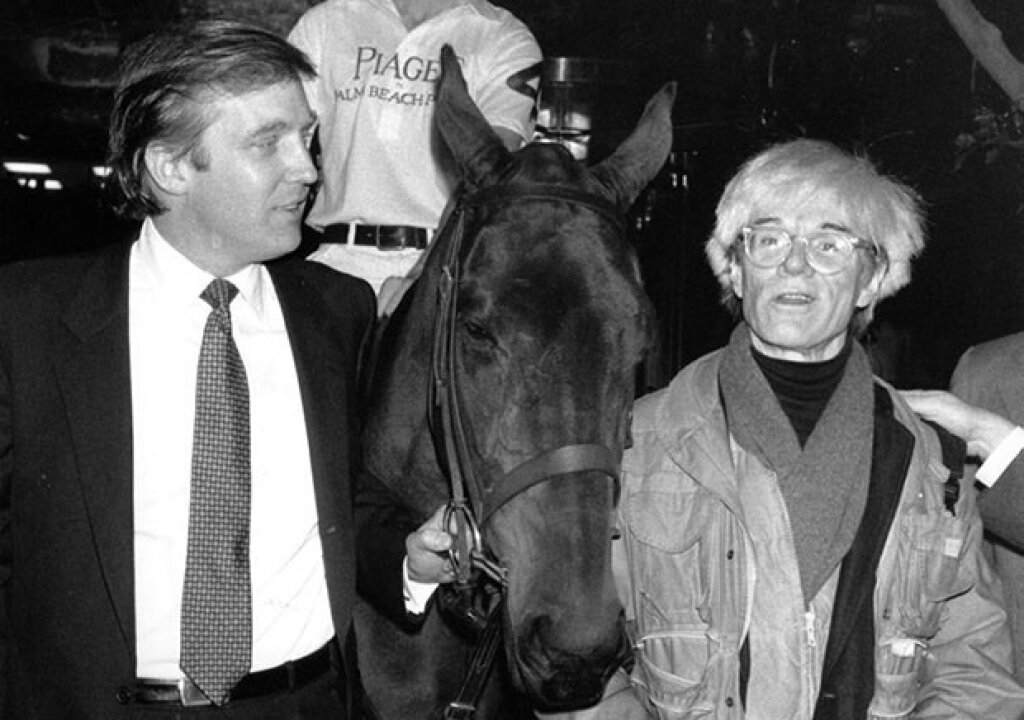

To be sure, not all postmodern art, literature and theory is emancipatory or ethically uncompromised. Combinations of postmodern culture and critical insights with cynical politics are as old as postmodernity itself, as my second epigraph, drawn from an interview with ur-theorist and practitioner of American postmodern architecture Philip Johnson, might demonstrate. And although we might share Lipovetsky’s view that the reality show called “the Trump presidency” is an impoverished and cynical work of art, we should also recognize that postmodernism, as a cultural movement, has never been well enough defined that one may reject Trump as “insufficiently postmodern” by some established criteria. Postmodernity’s political and cultural possibilities have room for both progressive and reactionary positions, and for everything in between—as was the case with all preceding sociohistorical moments, from the Enlightenment onwards.

Ultimately, our present cultural and political morass demands a different critical response. The fashion of “blaming postmodernism” for Trump and Putin, not to mention Erdogan, Le Pen, Brexit and everything else, is the facile pose of intellectual dandies like Pomerantsev or Ernst. Postmodernity, as it has been described by theorists from Lyotard and Jameson to Jean Baudrillard, is where we live. Excoriation of theorists, authors or the academy as the foundation of postmodern politics, as though the key to salvation lay in the adoption some of other philosophical positions, is patently absurd (and quite possibly lends support to reactionary politics of other varieties). Instead, what we need is an application of postmodern critical theory in order to demystify the practices of cynical political elites, yet also to agitate for political regimes and institutions that take into account our actual socio-historical condition, not in order to accumulate power, but rather to support rational discourse, democratic participation, respect for human rights and global economic justice.