This article was initially posted on The Monkey Cage.

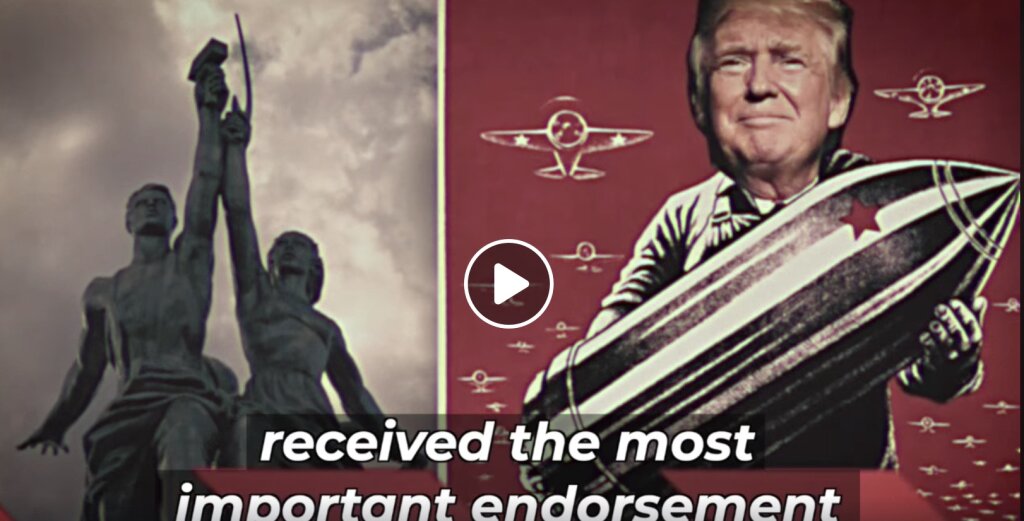

Over the course of the recent U.S. presidential campaign, Donald Trump broke new ground — especially for a Republican candidate — with his consistent praise of Russian President Vladimir Putin. With Trump now headed to the White House, I reached out to a number of Russian politics experts for their take on what this means for U.S.-Russian relations, as well as their expectations for the effect of a Trump presidency on Russian foreign policy more generally:

Yoshiko M. Herrera, professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Andrew H. Kydd, professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison:

Donald Trump has said that he wants to improve U.S.-Russian relations and in particular that he wants a closer relationship with Vladimir Putin. In 2009, Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton came into office as president and secretary of state, and they too wanted to improve relations with Russia. Is there any reason to suppose that this new reset will fare any better than the previous one? One reason it might is Trump’s apparent interest in reducing traditional American commitments abroad, particularly to the United States’ NATO allies. Trump has often questioned the continuing value of NATO and characterized some allies as free riders who do not necessarily deserve to be defended. Putin’s foreign policy is animated by a desire to restore Russian power and influence. If the United States were to step back from the European arena, Putin would be happy to step in. However, such a development, which might seem to improve U.S.-Russian relations, would be heavily criticized in the U.S., not to mention in Europe, as a surrender to Russian ambitions and a selling out of American national interests.

Moreover, given Trump’s mercurial temperament and unpredictability, he could easily decide to reverse a policy of conciliation and stand firm at some point. This kind of uncertainty about the extent of American commitments is highly conducive to conflict. The Korean War started in part because Kim Il Sung and Stalin thought the United States had written off South Korea after the Communist victory in China. Dean Acheson had not included South Korea in the United States’ stated defense perimeter in the region, but when push came to shove, the United States decided to fight anyway. Attempting to conciliate Russia by weakening our commitment to NATO, therefore, is a very risky path to better relations, especially if it is not domestically sustainable.

Dmitry Gorenburg and Michael Kofman, research scientists, CNA, a nonprofit research organization. The views expressed here are their own and do not represent CNA.

Donald Trump’s victory has the potential to fundamentally reshape U.S.-Russian relations, but whether such a realignment will actually take place will depend on how Trump chooses to learn and appreciate the past failures of several U.S. attempts to engage Russia. It remains to be seen whether he will be willing to follow the advice of professionals, or if he will strike off on his own. U.S.-Russian relations are founded on a complex history, with structural differences among national elites that will prove difficult to bridge through personal rapport among the national leaders. Trump’s first problem will be that other than a small number of close advisers who share his instincts to engage Putin, most of the policy establishment is likely to hold hardened views of Putin’s Russia, ranging from distrustful to confrontational. Rapid change is unlikely to come quickly, despite the personal attention of the president-elect, because the bureaucracy will initially take an obstructionist position.

Having said that, we can make a few predictions regarding policy initiatives that are likely to be undertaken by President Trump. First of all, he is likely to restore the full range of government contacts, including between the two countries’ military establishments. Second, he will pursue more extensive cooperation with Russia in Syria, against ISIS but also against other anti-Assad groups that could conceivably be described as Islamist. Most likely there will be a complete abandonment of the existing policy formulation that there is a moderate Syrian opposition and viable alternatives to Assad, which will closely bridge the U.S. position with that of Moscow’s. And finally, the active sanctions policy against Russia is likely to end, though existing sanctions will not be lifted without a quid pro quo.

And this brings us to the heart of the matter. Trump is at his core a dealmaker. He will want to make a deal with Putin. And he doesn’t care very much about the core issues that have been driving the conflict in the U.S.-Russia relationship for the last five to six years: democracy promotion in Russia’s near abroad, human rights, NATO expansion and contesting Russian influence in Europe. Russia’s core interests, keeping Ukraine and Georgia in its sphere of influence, and pursuing an integration agenda toward the Soviet Union’s former republics is not antithetical to how Trump will define U.S. national interest. As a result, he will be willing to trade on a range of policies. However, this initial predilection to deal with Russia should not be mistaken for a simplistic approach to freely give Moscow that which it desires. Dealmakers don’t generally agree to trade something for nothing. So what happens next depends in large part on what Russia will offer in return. The Syria conflict is an obvious area for dealmaking. Another possibility is Russia making itself attractive as a potential partner in dealing with China. The inertia of distrust and confrontation may make a grand bargain elusive, and pursuing such lofty goals too quickly could actually jeopardize Trump’s long-term vision for a relationship with Russia, but in the short term he can make notable changes to the current bilateral relationship.

Andrew Barnes, associate professor, Kent State University

Since at least the invasion of Ukraine in 2014, most Russian foreign policy actions have made sense as opportunistic efforts to prod and weaken the Western-dominated international order. Putin and members of his administration have long seen that order as beneficial to the West at Russia’s expense, and they have made no secret of the fact that they believe it is intentionally structured to damage Russian interests. Such Russian actions as military overflights, ship deployments, involvement in Syria, and continued presence in Ukraine all serve to challenge the structures of the post-World War II system that has so benefited the United States and its allies. Other developments, like the refugee crisis, Brexit, and rising nationalist and anti-E.U. sentiment in general, have had similar effects, whether or not Russia had a hand in them.

With the American election, the United States has chosen a president who has professed similar negative views of the current international order, even if he does not believe those structures have benefited the United States. Trump has applauded Brexit, said he would defend only those NATO allies who paid their fair share, approved Russian strategy in Syria and Ukraine, and stoked an increase in nationalism in the U.S. similar to that in Europe. I expect that Russian will continue to press against existing international institutions and norms and that Trump will generally welcome those actions, as he thinks they benefit American interests. Potential conflict will only arise when it comes to creating new rules to replace the old ones. How that process will go is hard to predict, as neither Putin nor Trump has expressed very clearly what new order he would like to see replace the old.

Mariya Y. Omelicheva, associate professor, Department of Political Science, University of Kansas

Vladimir Putin, the president of Russia, was among the first world leaders to congratulate Trump. In a telegram addressed to the president-elect, Putin expressed his hope that Trump’s presidency would lift the U.S.-Russian relations from the current crisis. Putin’s optimism is not idle: Trump’s victory in the presidential elections may be a silver lining in the relations of these two states. The Kremlin has viewed the U.S. as Russia’s major competitor for regional influence in the former Soviet Union’s republics, an area that the Russian government sees as its legitimate sphere of interest.

The Trump government is likely to scale back the level of support for Ukraine, Georgia, and other post-Soviet republics, giving Russia greater freedom to pursue its national interests in these states. Revoking the U.S. sanctions on Russia for its annexation of the Crimean peninsula and the ongoing support of the rebels fighting in the east of Ukraine will be Russia’s ultimate prize.

While on the campaign trail, Trump raised the specter of the U.S. pulling out of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. If his administration acts on this and reduces American support for the alliance, it will effectively scale down the U.S. military posture in Europe, including the future deployment of NATO forces in the Baltic states and Poland. This will effectively remove the major bone of contention in U.S. relations with Russia. Lastly, Trump is unlikely to be vocal in his criticisms of Russia’s state of civil and political rights, and growing authoritarianism of Putin’s administration. Eliminating this irritant for Russia will show what Putin called the principle of “mutual respect” for Russia’s own way of political life.

Eric McGlinchey, associate professor of government, Schar School of Policy and Government, and Marlene Laruelle, research professor, George Washington University

U.S. favorability perceptions among Russians have plummeted. According to Pew’s Global Attitude survey, U.S. favorability perceptions among Russians dropped from 57 percent in 2010 to 15 percent in 2015. Much of this erosion in U.S. favorability perceptions can be attributed to how the state-run Russian media portrays Washington. And it’s not only in Russia where the Kremlin’s media outreach resonates. In Central Asia, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tajiks and Uzbeks see the Russian press as more reliable than Western media. Perhaps not surprisingly then, a majority of Central Asians polled in a 2015 Broadcasting Board of Governors/Gallup survey expressed support for Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

What will the state-run Russian media make of President-elect Trump who, as candidate Trump, (in)famously quipped “the people of Crimea, from what I’ve heard, would rather be with Russia than where they were?” Will the Russian press embrace the bare-chested Trump-Putin tandem of social media memes? Or will the Kremlin media machine grow weary of a mercurial Mr. Trump?

Today Margarita Simonyan, the head of Russia’s RT television network, tweeted she wants to “drive around Moscow with an American flag on her windshield.” Simonyan’s enthusiasm notwithstanding, the Kremlin’s media reset will likely be fleeting. American presidents, in contrast to post-Soviet autocrats, face considerable domestic constraints. Americans who voted for Trump did not vote for improved Russia-U. S. relations. They voted against a political system that for far too long ignored the growing disaffection of blue-collar workers. Russia, as his comment on Crimea reveals, is peripheral to Trump’s courting of disaffected America. Devoting attention to Putin does not advance Trump’s position with his base. As Trump and America turn inward, the best Russia — and the world — can hope for is to not be forgotten.