The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

Rustam Alexander is the author of Red Closet: The Hidden History of Gay Oppression in the USSR (Manchester University Press, 2023) and Regulating Homosexuality in Soviet Russia, 1956-1991: A Different History (Manchester University Press, 2021). His new book, Gay Lives and “Aversion Therapy” in Brezhnev’s Russia, 1964-1982, will be out this year from Palgrave Macmillan.

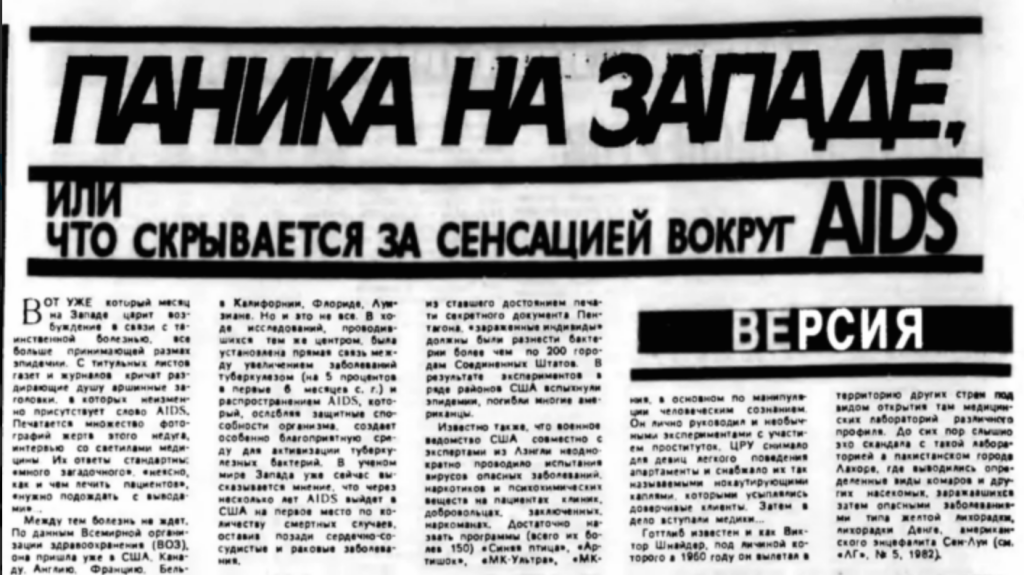

Above: A 1985 Literaturnaia Gazeta article by Valentin Zapevalov with the headline "Panic in the West, or what is hiding behind the sensation surrounding AIDS." This article and others were part of a KGB disinformation campaign called Operation INFEKTION.

Although the Western media began discussing the AIDS epidemic as early as 1981, it was not until 1983 that Soviet outlets mentioned the issue for the first time. In that year, Soviet epidemiologist Rem Petrov briefly described a mysterious disease on the pages of a major weekly, Literaturnaia Gazeta, explaining that it affected people’s immune systems and was common among homosexuals and drug addicts.

Petrov’s article remained the only publicly available source of information on AIDS in the USSR until 1985. Although Soviet officials knew about the issue, they barred doctors from initiating a public discussion on it, fearing panic and believing that the mysterious affliction would not affect Soviet society. Soon, however, to their dismay, the first cases of AIDS began to emerge on Soviet soil.

Now concerned that the epidemic would spread across the country, the Soviet Ministry of Health took measures, issuing instructions to regional Health Ministries about the little-known disease. Even more importantly, Soviet police were instructed to unleash a crackdown on homosexuals, who were deemed the main culprits of AIDS. At the same time, unbeknownst to Soviet doctors,the KGB launched a controversial AIDS disinformation campaign, accusing the US of having created the AIDS virus in its secret labs for future use as a biological weapon. This disinformation campaign wrought havoc on Soviet health officials’ attempts to control the spread of the virus at home and stymied the international community’s efforts to battle the epidemic. Only in 1988 did Soviet authorities finally backpedal on AIDS-related disinformation.

As the disease spread across the USSR, Soviet society was undergoing significant transformation. The new leader of the country, Mikhail Gorbachev, was introducing liberal reforms that gave the Soviet people freedoms they had never previously enjoyed. One such freedom was the freedom of speech, which made the issue of AIDS a matter of public debate. On the pages of Soviet newspapers and journals, officials, journalists, doctors, educators, and jurists blamed“risk groups”— homosexuals, prostitutes, and drug addicts—for spreading the virus. Some doctors even suggested that treating AIDS patients was not necessary, since it was “a natural means” of cleansing society of “scum.”

A spike in AIDS infections among newborn babies in Soviet hospitals in 1989, caused by medical negligence and lack of basic equipment, made the public and experts finally realize that it was the dire state of Soviet medicine, not the so-called “risk groups,” that had led to the uncontrolled spread of AIDS on Soviet soil. More compassionate views of homosexuality began to emerge in Soviet newspapers and journals. Even so, many experts still believed that homosexuality was an abnormality, fixable with medical treatment.

Although AIDS pushed the issue of homosexuality into the spotlight, it did not facilitate the emergence of a Soviet gay community. Homosexuality remained a punishable crime, despite mounting calls from doctors and jurists to remove it from the Criminal Code. Barring a few exceptions, many homosexuals still believed that their orientation was a “disease” and heterosexuality the only “normal” way to be. Legal punishment for homosexuality was removed from the books only in 1993, two years after the Soviet Union’s demise.

The history of HIV/ AIDS in the USSR still remains largely unexplored. Further research on this topic will not only contribute new insights into the history of Soviet law, medicine, and education, but also help us understand what lies behind the reluctance of Russian authorities to deal with the HIV/ AIDS pandemic in Russia today.