Irina Erman is Associate Professor of Russian Studies at the College of Charleston. Her primary area of expertise is nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Russian literature, with a focus on marginality, performativity, and monstrosity. She is the co-editor, with Lynn Patyk, of Funny Dostoevsky, forthcoming from Bloomsbury in 2024. She is currently working on a book on Fyodor Dostoevsky and performance.

An earlier version of this essay appeared on Bloggers Karamazov, the official blog of the North American Dostoevsky Society. A full-length article on this topic is available in open-source format in Russian Literature.

This is Part II in a two-part series. Part I may be found here.

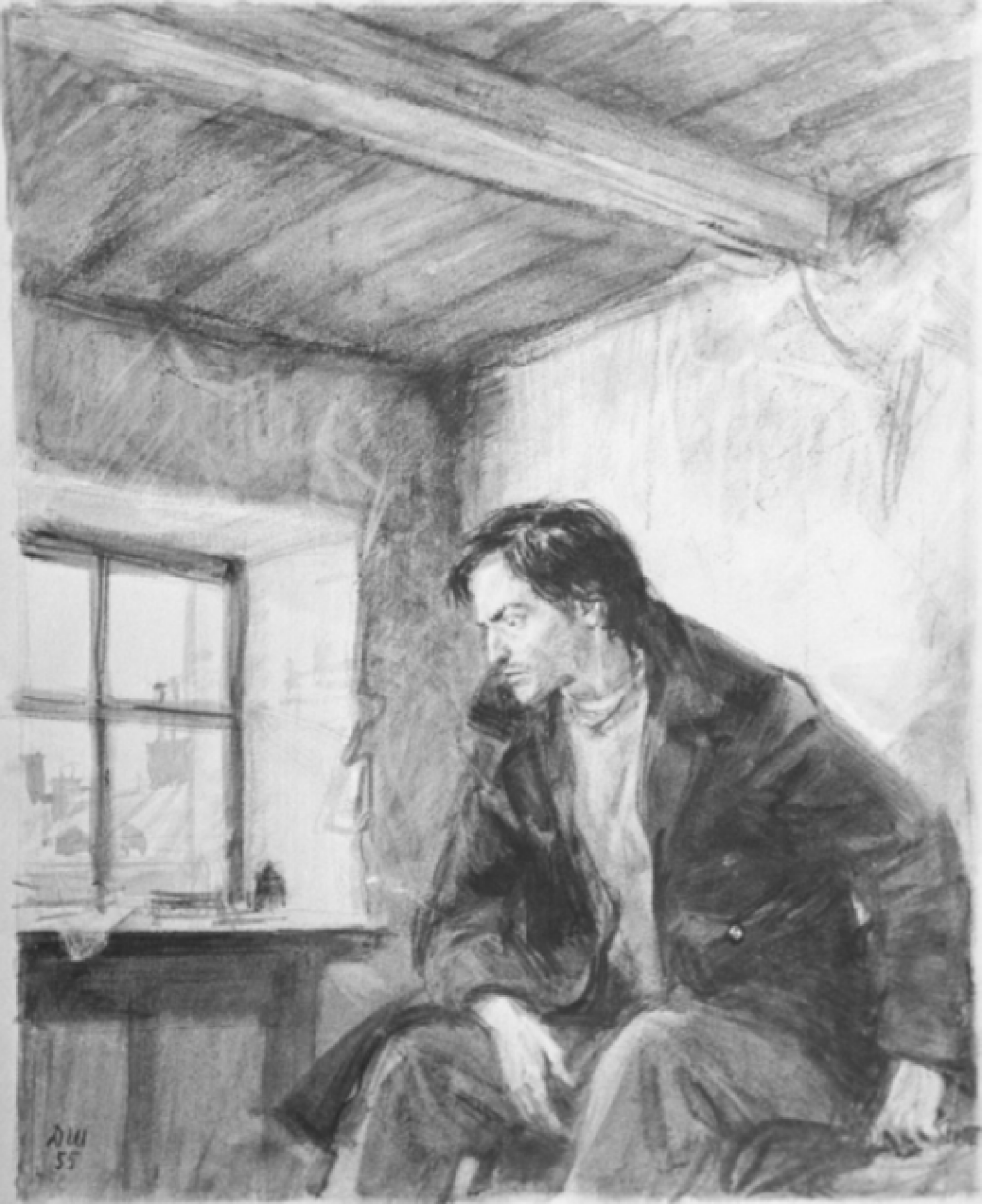

In Crime and Punishment, Raskolnikov kills two women. Throughout the text, however, he perpetually “forgets” the collateral damage of killing the 60-something pawnbroker: murdering her potentially pregnant 30-year-old half-sister who walks in as he is committing the first crime. The novel’s narration lays two traps to implicate us in Raskolnikov’s shady “arithmetic.” First, it elides and invites us to overlook the murder of Alyona’s sister, Lizaveta. Second, by manipulating the way we speak about the crime as primarily the murder of the pawnbroker, it insidiously suggests that one of the deaths is more acceptable. In other words, the novel leads its readers into falling into the same moral trap as Raskolnikov in evaluating one human life as less valuable than another. Raskolnikov is much more comfortable talking about the murder of the pawnbroker than that of her sister because her death aligns with the proposal articulated in the tavern scene: to sacrifice older, sicker, or “unproductive” members of society for the greater economic good.

Raskolnikov was intrigued by the idea of categorizing people as “worthy” or “unworthy” for some time before the tavern scene. As readers learn from his conversation with detective Porfiry Petrovich, six months before the murder, Raskolnikov dropped out of law school and wrote an article “On Crime.” The article claimed that every “extraordinary man” in history was essentially a transgressor or a criminal, since he had to go against established norms in order to enact change. From that rather unoriginal premise, Raskolnikov deduced that great men like Napoleon and Newton have a right, nay, even an obligation to commit crimes to accomplish their goals. The delusional hubris is, of course, already there in the “extraordinary man” theory, but it is in the tavern scene that Raskolnikov develops the additional layer of the “arithmetic” motive. Here, his desire to test his superiority as a potential Napoleon through crime meets the capitalist rhetoric of economic productivity and the utilitarian logic of “the greatest good for the greatest number of people.”

Dostoevsky undermines Raskolnikov’s idea by having it parroted by a drunken undergrad and by linking it with the motif of illness. It is ironic that Raskolnikov justifies selecting the old woman as his victim because she is economically unproductive and sick. Raskolnikov is himself perpetually ill, does not work, and relies on charity from the women in his life: his landlady, his landlady’s servant Nastasya, his mother, his sister, and later, Sonya Marmeladova.

He starts to feel feverish just as he recalls the tavern scene and the impression it made on him. He feels so ill that he collapses into bed and cannot get up the next morning when Nastasya brings him some of her own leftover tea. Even the otherwise lighthearted Nastasya starts to worry when she realizes Raskolnikov can’t muster the strength to eat or drink, concluding: “Maybe he really is sick.” Raskolnikov, for his part, spends most of that day in bed, drifting in and out of consciousness. Ultimately, his illness makes him miss his window of opportunity for an uninterrupted murder—directly leading to the second killing.

When Raskolnikov finally gets out of bed and starts to feverishly prepare to go to the pawnbroker’s, he recalls his article “On Crime.” Perhaps the only original idea in the article was Raskolnikov’s emphasis on illness as a sort of litmus test, in which “great men” who transcend morality can be identified because they are not susceptible to the physical symptoms that plague regular criminals. While his focus on asymptomatic carriers is novel, Raskolnikov’s association of crime with disease draws on one of the founding metaphors of political thought, in which the political community is seen as a body and crime – as a break-down in its normal functioning.

In the mid-1970s essay collection published as Abnormal, Michel Foucault explains that, “According to a tradition found in Montesquieu but going back to the sixteenth century, the Middle Ages, and also to Roman law, the criminal, and especially the frequency of crimes, represents a disease of the social body.” Toward the end of the eighteenth century, however, a new conception of the relation between illness and crime develops, in which “it is not crime that is a disease of the social body but rather the criminal who as such is someone who may well be ill.” Raskolnikov’s “On Crime” clearly draws from this later strand of thought. As he considers the article on the eve of the murder, Raskolnikov does not “yet have the strength to resolve the question: is it the illness that begets the crime, or is it the crime itself, somehow by its own nature, that is always accompanied by something akin to illness?”

It is not necessarily an either/or question, and Raskolnikov’s own experience suggests that both conclusions could be valid. Yet Dostoevsky’s language makes clear that the former is more important for the novel’s main theme. Raskolnikov’s contemplation of the crime prior to committing it is marked by illness, and particularly by what Dostoevsky calls “likhoradka.” This multi-valent word can describe both fever itself as well as a state of “feverish” anxiety. Dostoevsky both highlights and takes advantage of its multiple meanings. Rather than a specific medical diagnosis, likhoradka is a legible, embodied sign of nervous shock, mental disorder, or infection. It dramatizes what might otherwise remain hidden by literally writing it on the body through violence. In Raskolnikov’s case, that violence also spreads to other bodies, whether through his delirious actions or potential infection. Porfiry Petrovich even worries that Raskolnikov’s illness could spread to his friend Razumikhin: “You have a disease, while he has goodness, and it turns out your disease is contagious for him.”

Early in the novel, when Raskolnikov can only refer to his planned crime as “that,” the very thought of it makes him shudder and his mental turmoil manifests in physical symptoms. “His nervous shaking (нервная дрожь) turned to feverish shivering (лихорадочную), and he even started to feel chills (озноб).” Exhausted and cold despite the summer heat, Raskolnikov collapses in some bushes and experiences the first of his memorable fever dreams—the nightmare vision of a horse being beaten to death by a drunken crowd that has just emerged from a tavern. He wakes up covered in sweat and certainly feeling no better.

It is in this state that he remembers the other tavern scene, when he first heard the words “Kill her and take her money.” That memory concludes with the return of his “prior fever” and “chills,” which render him bedridden on the eve of the murder. When Raskolnikov wakes up much later than planned, his likhoradkaturns from fever to agitation as he rushes to finish his preparations, consumed by “an extraordinary feverish… bustle.” When he finally arrives at the pawnbroker’s apartment, it is not clear whether his state is the result of fever, nerves, or both. The old woman is alarmed by the pale, trembling, and sweaty man at her door, but she finally lets him in when he explains that it is just “likhoradka.” She should perhaps have been more alarmed by the word choice. The term likhoradka comes from the words likho, meaning “evil” or “ill,” and radit’, “to wish.” Even at the level of language, then, Raskolnikov’s illness is associated with “wishing ill.” Moreover, his physical symptoms belie his hope that he can be the rare man who can “wish ill” without, in fact, becoming ill himself.