Megan Swift is an Associate Professor of Russian Studies at the University of Victoria (Canada).

Yesterday and today. Broadly speaking, this is the theme at the heart of my recently published book, Picturing the Page: Illustrated Children’s Literature and Reading Under Lenin and Stalin (University of Toronto Press, 2020). In Russian cultural history, “yesterday and today” continues to resonate as a theme, since the Putin state is just as invested in controlling the narrative of the Soviet past as the Soviets were in harnessing the past of Imperial Russia.

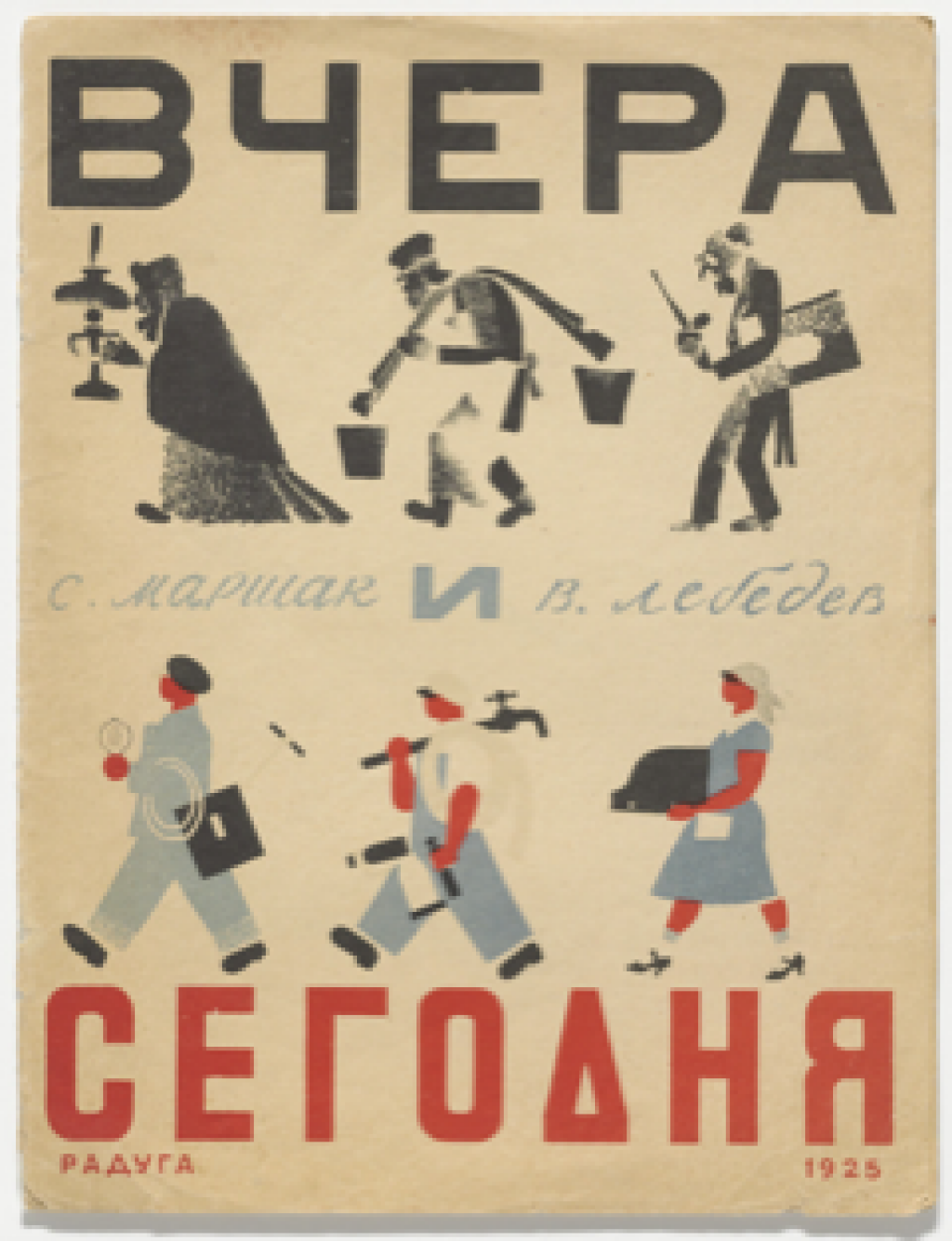

Vchera i segodnia (Yesterday and Today) is also the title of a 1925 picture book by leading Soviet children’s author Samuil Marshak. In the illustrations by Vladimir Lebedev, "yesterday" is represented by a series of old-fashioned household items like the inkpot and water bucket, which appear hopelessly outmoded by new technologies like the typewriter and water tap. But when the kerosene lamp is called a glupaia baba (foolish peasant woman) who must step aside for the arrival of the new “citizen,” the electric lamp, it becomes clear that human categories are also being judged as antiquated and useless.

“Yesterday and today” is thus a conceptual category that connects children’s picture books to the larger campaigns that shaped cultural policy under Lenin and Stalin. My book analyzes the interconnections between children’s literature, book illustrations, and the changing and often contradictory cultural contexts that produced them, since the past was a reviled category under Lenin and a revived and reinvented one under Stalin.

Book illustrations had a complex and multifaceted function in this context. They reached young readers in unprecedented numbers when mass state publishing for children was established in the 1920s. They appeared for the first time in the public school classroom when universal education and textbook publishing were initiated in the 1930s. (My book is the first to take into account the illustrations that mediated the curriculum in the state textbook Russian Literature.) Another new function of illustrations was to repurpose the past in “adult” literature reformatted for children, otherwise known as children’s reading. The texts of the past remained fixed, but newly-created illustrations could slip between the pages to mediate and annotate “yesterday” in line with the priorities of “today.”

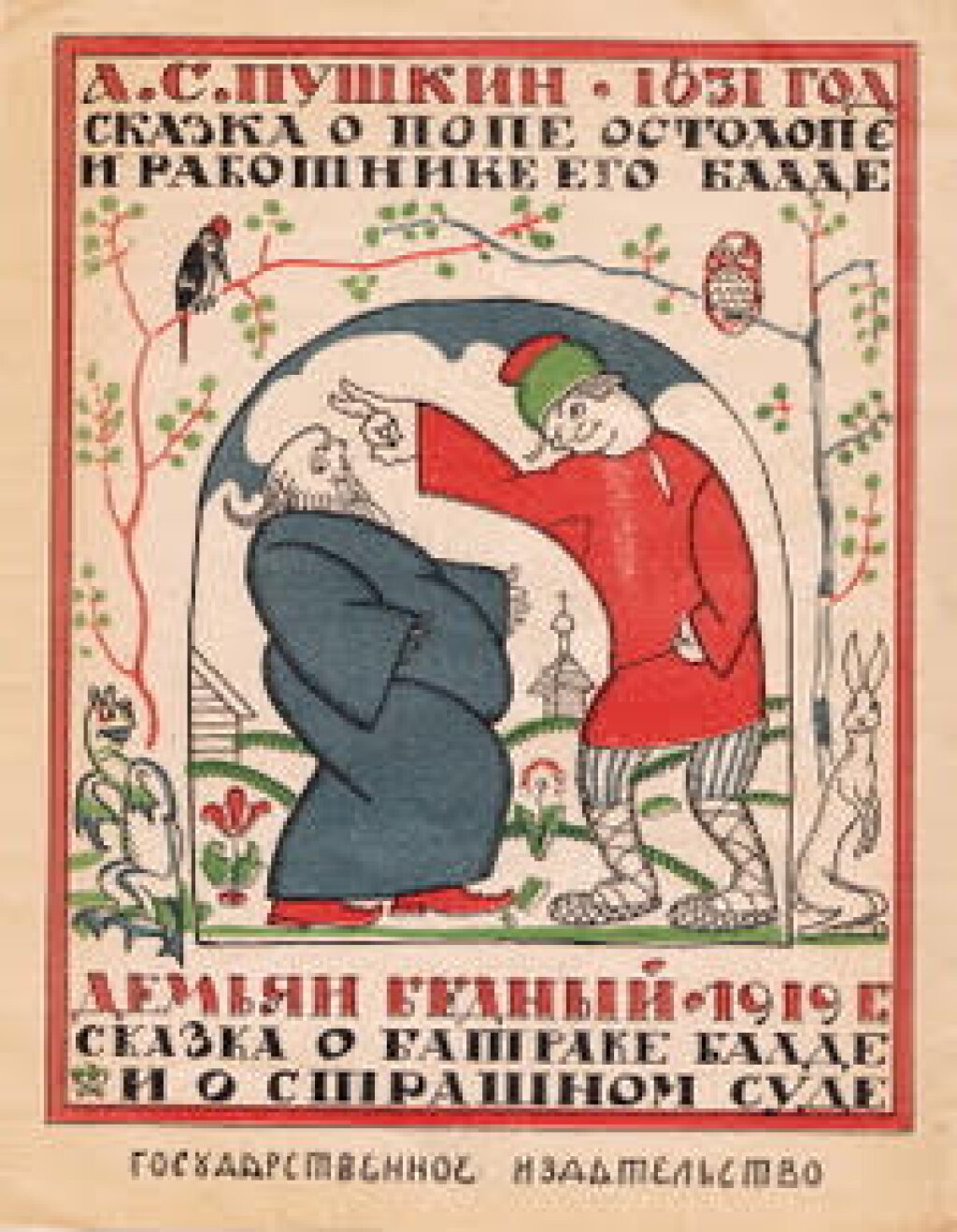

In Soviet republications of Pushkin’s satirical fairy tale “The Tale of the Priest and His Worker Balda,” illustrations achieved a visual reversal of fortune in the stand-off between two politically charged figures, the priest and the peasant. Connecting to contemporary campaigns to consolidate state atheism and collectivize the countryside, illustrated versions of this tale initiated a new conceptualization of its villain and hero.

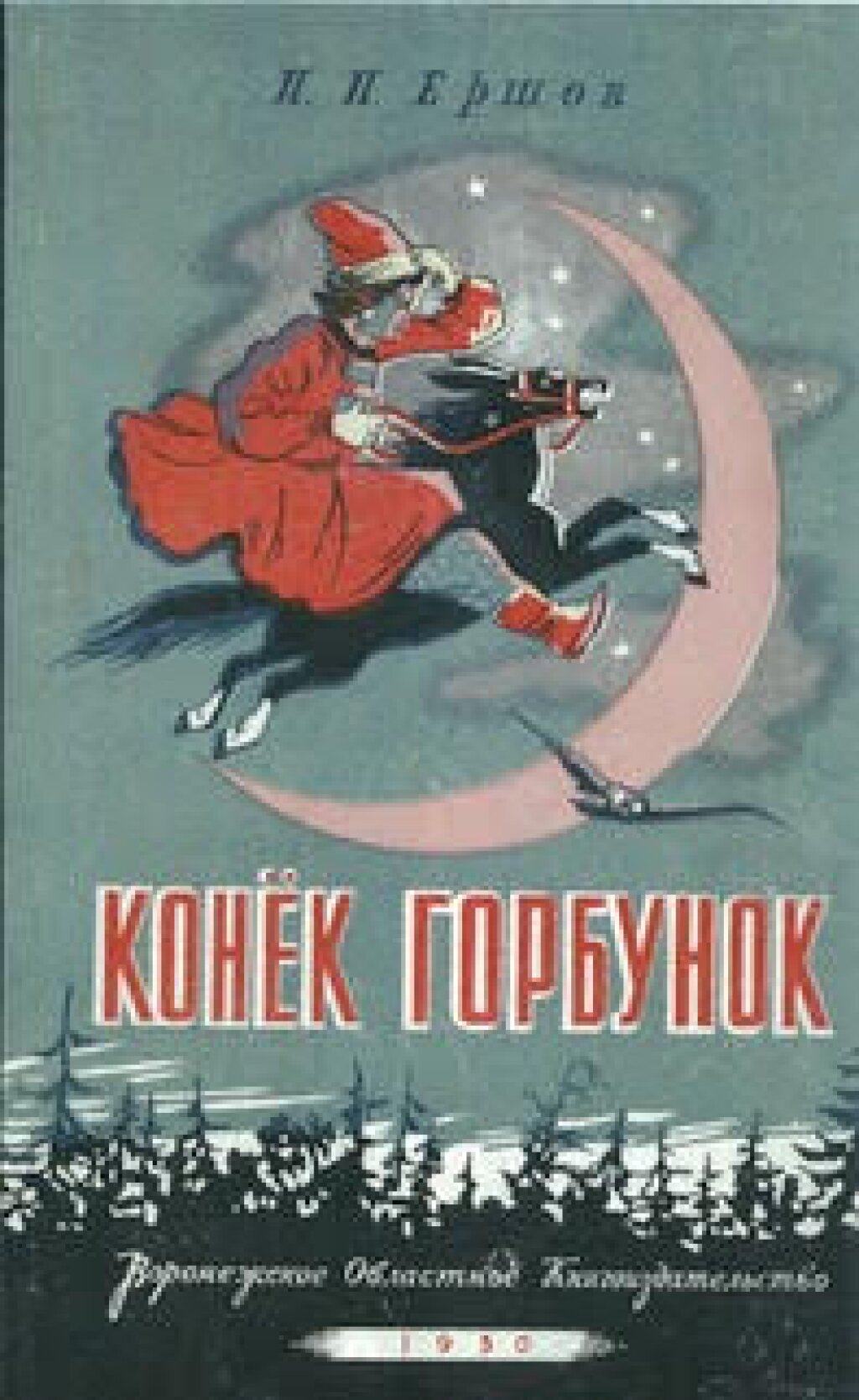

In Ershov’s “The Little Humpbacked Horse,” illustrations transformed the two underdog protagonists in a visual reimagination that placed Ivan the Fool and his flying humpbacked sidekick against a backdrop of heroic aviation and a state-sponsored, Union-wide obsession with “traveling the realm” known as stranovedenie, or "country studies."

Illustrated versions also breathed new life into Russian classics produced for children. At the beginning of the 1930s, Pushkin eclipsed Tolstoy as the most republished classic. Three new commissions for illustrations to Pushkin’s Bronze Horseman were made in honor of the massive Pushkin anniversary of 1949, all referencing the “storm” that Petersburg had recently weathered. Depictions of collective efforts to rescue neighbors and save neighborhoods were particularly poignant in light of the recent brutal suppression of Siege of Leningrad commemoration by the Stalinist state. The unmistakable setting of the “storm survivors” permitted select illustrations to double as clever circumventions of the Leningrad-exceptionalism ban. In the schools, illustrations to The Bronze Horseman were used to underline a narrative of state might at the expense of the individual.

During the war, illustrated children's books were featuring a new past. By 1941, twenty-four years had passed since 1917 — a period long enough to produce a new generation. Wartime picture books could address a dual audience: the first Soviet generation of child readers and their children. At this point, the 1920s were reconfigured as a native, shared past with a native, shared library. Texts originating in the 1920s, like Vladimir Mayakovsky’s “Let Us Take the New Rifles,” were reimbued with meaning in illustrated versions from the 1940s and used to bring together two generations of readers through works that were newly conceived as classics in a Soviet canon of literature.

When the lion of children’s books and publishing, Samuil Marshak, traveled to the front during the war to read his newly-composed patriotic poems, he was surprised by requests from the soldiers to read aloud their old childhood favorites, like Mail (1927, illustrated by Mikhail Tsekhanovsky), a story about a letter that travels all around the world in pursuit of its itinerant addressee. This moment marked an important watershed in Soviet children’s culture, an instance when the first readers of post-revolutionary literature could reflect back upon a trove of favorite childhood rhymes, stories, characters and images and actualize the first canon of Soviet children’s literature.

Marshak and other wartime writers were inspired to write sequels to their works of the 1920s, resulting in Wartime Mail (1944, illustrated by Adrian Ermolaev), which revisited the Leningrad postman of the original and celebrated the feats of the “mailmen for the front.” The illustrated sequels connecting the 1920s to the 1940s allowed Soviet children’s literature to be self-referential and address its own past, instead of correcting and updating a “foreign” imperial one.

[gallery ids="6261,6260"]

Illustrations to children’s literature in the Lenin and early Stalin years, the formative first decades of the Soviet state, allowed for a significant reconfiguration of the past. Not only did illustrations appear in new works about the past; they also acted as cues and commentaries inserted into the texts of the past themselves, the voice of today mediating the words of yesterday. My book highlights illustrations as uniquely flexible and mobile cultural products that circulate through successive audiences of child readers, linking older generations to younger ones through a shared cache of images while also moving fluidly through a fixed piece of work in successive editions, accruing new meanings and associations. Illustrated sequels recirculate meaning by hearkening back to origin texts and reaching forward to new communities of interpretation. Through circulation, illustrations moved and interacted with texts, cultural contexts and reading audiences, updating and shifting narratives of the past.

Many of the cultural shifts I analyze in my book are still relevant in post-socialist Russia. The illustrated children’s books of the Lenin and Stalin eras continue to appeal to young readers and their parents. Indeed, reprints of these Soviet classics are often considered to be of higher intellectual and professional quality than newly-produced works. Soviet illustrated children’s literature has thus become a means for expressing shared cultural values in a time of uncertain post-socialist identity.