Katherine Bowers is Assistant Professor of Slavic Studies at the University of British Columbia. She is working on a book about the influence of gothic fiction on Russian realism and tweets about Russian lit and other things on @kab3d. She also edits Bloggers Karamazov, the blog of the North American Dostoevsky Society, and curates the Society’s social media.

A version of this post appears on The Bloggers Karamazov, the Official Blog of the North American Dostoevsky Society.

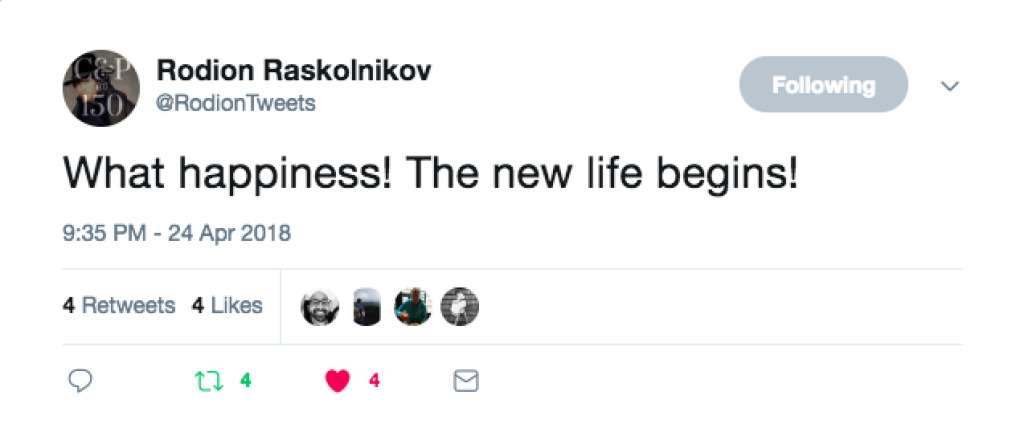

Two years ago, on May 1, 2016, the Twitter account @RodionTweets sent its first Tweet. Since then @RodionTweets has livetweeted the events of Dostoevsky’s novel Crime and Punishment, broken into 140-character-or-less snippets, from its hero Raskolnikov’s perspective. The bulk of the novel’s events take place over the course of three intense weeks in the summer, and the bulk of Rodion Raskolnikov’s tweets similarly appeared in July 2016, but the account has continued to tweet the book’s epilogues, which spread over the course of nearly two years. Finally, on April 24, 2018, Raskolnikov’s new life began and the Twitter account went silent.

@RodionTweets was the brainchild of myself and Brian Armstrong, a kind of extension of our first experiment with Twitterature, @YakovGolyadkin. Both accounts were created through a process of Tweet mining. For @RodionTweets we received permission from Penguin Classics to use Oliver Ready’s translation of Crime and Punishment. Then one Dostoevsky scholar mined one of the novel’s six parts and Kristina McGuirk, my wonderful RA, did a round of edits and loaded the Tweets into TweetDeck, scheduling them in to Tweet out according to the timeline for the novel that Brian and I had mapped.

As each part of the novel was Tweeted out, we reflected on our experience in creating the Tweets in a series of blog posts. Sarah Hudspith mined Part 1 and reflected on the divide between public and private online and the use of hashtags as a narrative device. In her discussion of mining Part 2, Sarah Young considered the way digital approaches to the novel (tweeting, digital mapping) expand our avenues for understanding and interpretation. Kate Holland’s experience mining Part 3 led to a new perspective on the novel’s narrative structure. Brian Armstrong discussed the insight he gained into empathy in both Crime and Punishment, Part 4 and The Double through the intensely close scrutiny Tweet mining requires. Jennifer Wilson’s mining of the scandal scene in Part 5 led to her reflection on social status and projection, and how pain, humiliation and suffering impact them. And my experience mining Part 6 and the epilogues led to a new realization on my part about timing in the novel. The blog post you’re reading serves as the project’s final, final note: one last reflection on what we’ve learned from @RodionTweets.

Of course, the first thing we, as literary scholars, noticed was that twitterifying Dostoevsky raised a number of questions that made us see the novel’s narration and themes in a new light. You’ll notice this from the blog post topics above. We began, however, with a basic question: how do you break a novel that’s narrated in the 3rd person down into Tweets in the first person? Where does the narrator’s voice go? The switch from 3rd person narration to 1st reverses Dostoevsky’s own narrative switch from the 1st person he originally planned on to the 3rd person the novel ended up with.

One of the conceits of the project is that Raskolnikov Tweets as if he keeps a constant feed of everything that goes through his head. This, of course, means that the account presupposes that no one else from the novel world is reading it. For example, Raskolnikov live Tweets the murder on @RodionTweets, and if Porfiry Petrovich were to read this in his Twitter feed, the novel would likely have been much, much shorter! – although this point is well taken. This style also renders @RodionTweets more like those Dostoevsky protagonists who monologue or write zapiski and less like most (active) Twitter users, who may do this kind of livetweeting some of the time, but not all of the time. Furthermore, as we mined the novel’s text for Tweets, thinking critically about what would be omitted from the Twitter narrative and what would be emphasized, as well as what Raskolnikov would be Tweeting about, we created a feed that both captures the novel’s tone and renders the work more real-feeling, or, at least, more contemporary.

This contemporaneity was a really unexpected yet rewarding result of @RodionTweets. Beyond the experience of Raskolnikov’s tweets periodically appearing in his followers’ twitter feeds, the serendipity of their timing or placement allowed for connections to be drawn between followers’ lived experiences and Dostoevsky’s novel. Followers remarked on the eeriness of @RodionTweets juxtaposed with twitter updates about the Turkish coup attempt or the odd resonance between @RodionTweets and the mood of many in post-Brexit Britain. One of the strangest coincidences was that Raskolnikov’s monologue leading to his confession took place at the same time as Trump’s speech at the RNC in Cleveland on July 21, prompting a flood of comments from followers experiencing the two feeds – RNC live Tweeters and @RodionTweets – together; here are a few examples. While unintended when we conceived the project, these juxtapositions highlight the power of Dostoevsky’s novel and speak to the relevance of his hero’s psychology for the present.

The project, though, was not all serious. Beyond the geopolitical resonances and the literary analysis, it is a project based in Twitter, a medium that’s equally political squabbling and entertaining puns, jokes, and sarcasm. The spirit of the project is one part Dostoevsky, one part Twitterature, and it also encompasses @RodionTweets’s love of strange hashtags and sublime Twitter moments such as when a Dostoevsky account interacting with his creation or a Shostakovich account liking some of @RodionTweets’s Tweets. Or this, my favorite follower interaction with the account, which continues to crack me up nearly two years later.

So what now? We have archived the project here: @RodionTweets, parts 1-3; @RodionTweets, parts 4-6 + epilogues. The archives are complete and tweets within them appear in chronological order (so you can read them alongside the book). They have already been used in the classroom by some. Professors assign students to read part of the novel alongside the corresponding tweets and then discuss, or to generate their own tweets from a different character’s perspective (this last idea is an assignment Kate Holland has implemented in her Dostoevsky class). If you are using the project in your class, please let me know!

At the end of my blog post about tweeting Part 6, I concluded by saying that the epilogues on Twitter would be spread across 18 months and then Raskolnikov would fade away. Now, though, I think that statement needs some revising. The spring of 2018 feels far removed in many ways from the summer of 2016. Much has happened since then. But I think the drawn-out nature of the epilogue, and Raskolnikov sporadically appearing in our feeds, has perhaps made it seem more like he is one of us – a Twitter user who is sometimes active (the conceit being he somehow manages to get online from his Siberian prison camp…), but more often not. And perhaps this silence is simply because his life is full and he hasn’t got time for social media. In this sense, although @RodionTweets has gone quiet, I hope he is not forgotten, but lingers on as part of our network, somewhere on the edge of our consciousness.