On Thursday, October 11th, the Jordan Center hosted Professor Harsha Ram for the talk “Khlebnikov, Tatlin, and the Utopian Geopoetics of the Russian Avant-garde”. Harsha Ram is Associate Professor in the Departments of Slavic Languages and Literatures and Comparative Literature at U.C. Berkeley, the author of “The Imperial Sublime: A Russian Poetics of Empire” (2003), and is currently working on a project on the Russian Revolution and world literature, on which this talk was based. NYU Visiting Professor and Assistant Professor of Russian at the University of Professor Colorado Boulder Jillian Porter introduced the talk as a part of the Occasional Series.

Harsha Ram’s paper focuses on the poetics, the literary theory, and the politics surrounding the Russian Revolution, and how the particular “convergence of literature and politics can help rethink the problem of world literature.” The paper is comprised of three segments, the first of which concerns poets’ responses to the political upheavals that marked the early 20th century. The second segment deals with the problems of utopia: the relationship between poetics and utopian thought in the context of the Russian Revolution, and, more broadly, the problem of utopia as conceived by Western scholars. The third segment focuses on geopoetics, and posits the argument that the modernist poet Velimir Khlebnikov provided an epistemological vision of the Eurasian space through the model of modernist abstraction. The final and fourth segment shines light on the largely overlooked Khlebnikov text “Zangezi”, a play that artist Vladimir Tatlin staged several times before it met its end. The play, according to Ram, propels ideas about the utopian and planetary implications of the Russian Revolution: it conceives of a post-revolutionary Russian-Eurasian space guided by new understandings of space, time, and language.

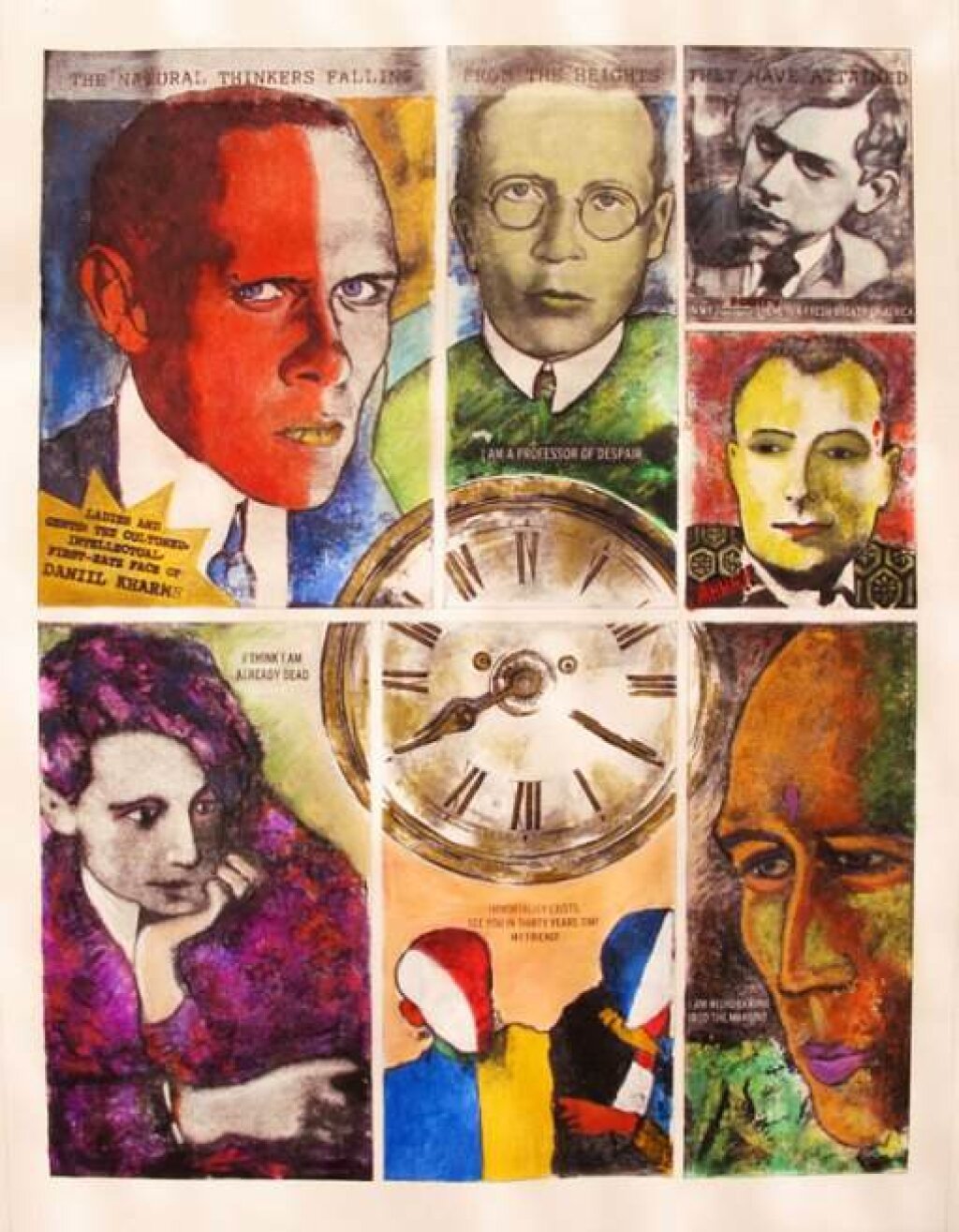

In his segment on poetic responses to the Russian Revolution, Ram features a varied array of poets that offer, as he commented, a “mixture of enthusiasm and dread” in regards to the transpiring events. As an example, Ram cited Boris Pasternak’s “Spring Rain” that explains the events of 1917 as an archaic force erupting into Russian civic life. Similarly, Alexander Blok in his poem “The Twelve” likens the revolution to a sweeping blizzard. Poet Osip Mandelstam examines the revolution through a mythopoetical framework, focusing on the interplay between remembrance and oblivion, while modernist Vladimir Mayakovsky incorporates ancient poetic traditions to synthesize an odic praise for the revolution. All of these different responses evoke the sentiment of what Professor Ram refers to as “millenarian eschatology”.

Velimir Khlebnikov, unlike the aforementioned poets, broke with the eschatological, quasi-Christian thread, instead formulating a “rationally-constructed linguistic utopia”. According to Professor Ram, Khlebnikov’s visions culminate in what the poet himself referred to as his “super-saga”, the play “Zangezi”. The play’s name is a neologism formed by a combination of the names of two rivers: one that flows through Africa, and another that flows through India. The neologism provides a hint at the fundamental geopolitical vision that permeates throughout the text, and had been previously unfamiliar to the Russian, eurocentric literary tradition. The piece, according to Ram, posits “a new vision of world history, geography, as well as a universal language”, and its impact, although not wide-reaching, was profound on select figures of the Soviet avant-garde and the left intelligentsia.

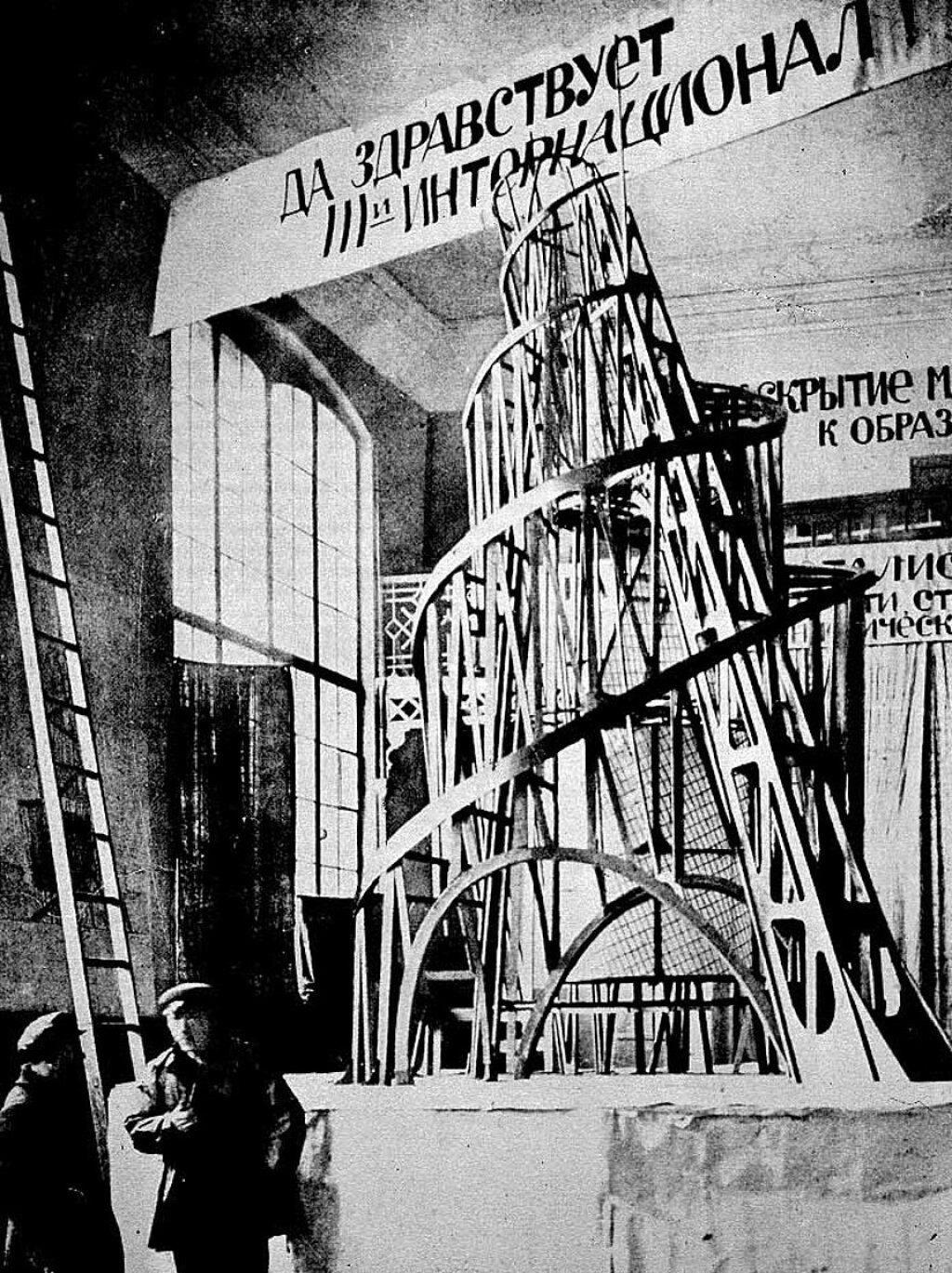

Russian constructivist artist Vladimir Tatlin staged the play three times at his establishment, the Petrograd Museum of Artistic Culture, an institution that Professor Ram referred to as “the world’s first museum dedicated exclusively to contemporary art.” “Zangezi”, according to Ram, can be juxtaposed with the design for “Tatlin’s Tower”, an iconic planned monument intended to serve as the headquarters of the Comintern. Both “Zangezi” and “Tatlin’s Tower”, working with the poetics of space, attempt to mirror the global resonance of the Bolshevik Revolution. In his paper, Professor Ram aims to explore in these avante-garde works the tension between the concreteness of time and place, and a turn towards abstraction; an aestheticized planetary internationalism that spawns from the revolution,

Professor Ram pushed forth the argument that while most debates concerning the Russian artistic representation of utopia focus on visual art, i.e. Malevich and the suprematists, Khlebnikov’s written work offers an “even richer” representation of utopian ideas. KHlebnikov likewise provides a method of breaking between the two spatial models defined by world literature: the territorial nation state, and the de-territorializing force of the world market. One of the major focuses of the paper will be the contrast between totality and infinity; between closure and liberty – and the role of geopoetics in mediating between these forces.

According to Ram, the Russian avant-garde embraced and adapted European artistic movements, while also embarking on a nativist trajectory – taking inspiration from cultures spread out across the dismantled Russian empire. As an example, Ram cites a quote by the modernist painter Natalia Goncharova, in which the artist, admitting that her early artistic development was grounded in her French contemporaries, admits a desire to aspire toward nationality and the East in order to make her art “all-embracing and universal.” This new endeavor, Ram argued, was an attempt to reorientalize: to propose an alternative universality – which for the Russians, had always been based on Western aesthetic and political principles. The idea of a tilt to the east, Ram added, can be traced in Khlebnikov’s work and his attempt at making a new language. Birdsong can be found in “Zangezi”, indicating Khlebnikov’s desire to make an encyclopedia of sound that Ram described as “full of phonic possibilities of erasing existence as a whole.”

For the remainder of the talk, Ram deconstructed the synthesis of Cubism, Italian Futurism and Constructivism in “Zangezi”, specifically when dealing with force and language. Ram likewise highlighted the specific elements within the both the diegetic world and stylistic form of “Zangezi” that indicate an internationalism of “poetic and cognitive innovation designed to unify the human race in tandem with the goal of world revolution”. In the Q&A segment, Professor Ram was asked how, without concrete geographical referents in the text, can the work be characterized as Asiatic. In response, Ram recalled how Khlebnikov had written several manifestos on the West’s colonialism of Asia, implicating Russia in the process as well. Professor Ram also mentioned the fact that Khlebnikov was born in the Kalmic Steppe and expressed a deep interest in the naturalistic history of both the region, and of Eurasia as whole.