In the 1965 Soviet film “I Am Twenty” (Mne dvadtsat’ let), the term Kvas patriotism explains the protagonist Sergei’s reverence for the potato. Upon his return to Moscow following his military discharge, Sergei has fallen in love with an unattainable privileged contemporary, Anya. At a gathering at Anya’s expansive central flat, Sergei confronts the decadence of his generation when party guests, including Anya, waste potatoes meant to complement the fest’s table. By contrast, earlier that evening in their modest communal apartment, Sergei witnessed his mother finding the WWII-era ration cards she had misplaced inside a book years earlier. The discovery triggers his mother’s memory of digging for potatoes by night, after work, to ward off hunger for young Sergei while her now-deceased husband served at the front.

These scenes from “I Am Twenty,” were part of Professor Angela Brintlinger’s October 21 lecture, “Kvas Patriotism in Russia: Cultural Problems, Cultural Myths.” Angela Brintlinger, Professor of Slavic Languages, Literatures and Cultures at Ohio State University, has written on literature, war, and madness, and recently published two books about food and culture. The talk, as part of the Occasional Series, was introduced by Bruce Grant, Professor and Chair of Anthropology at NYU.

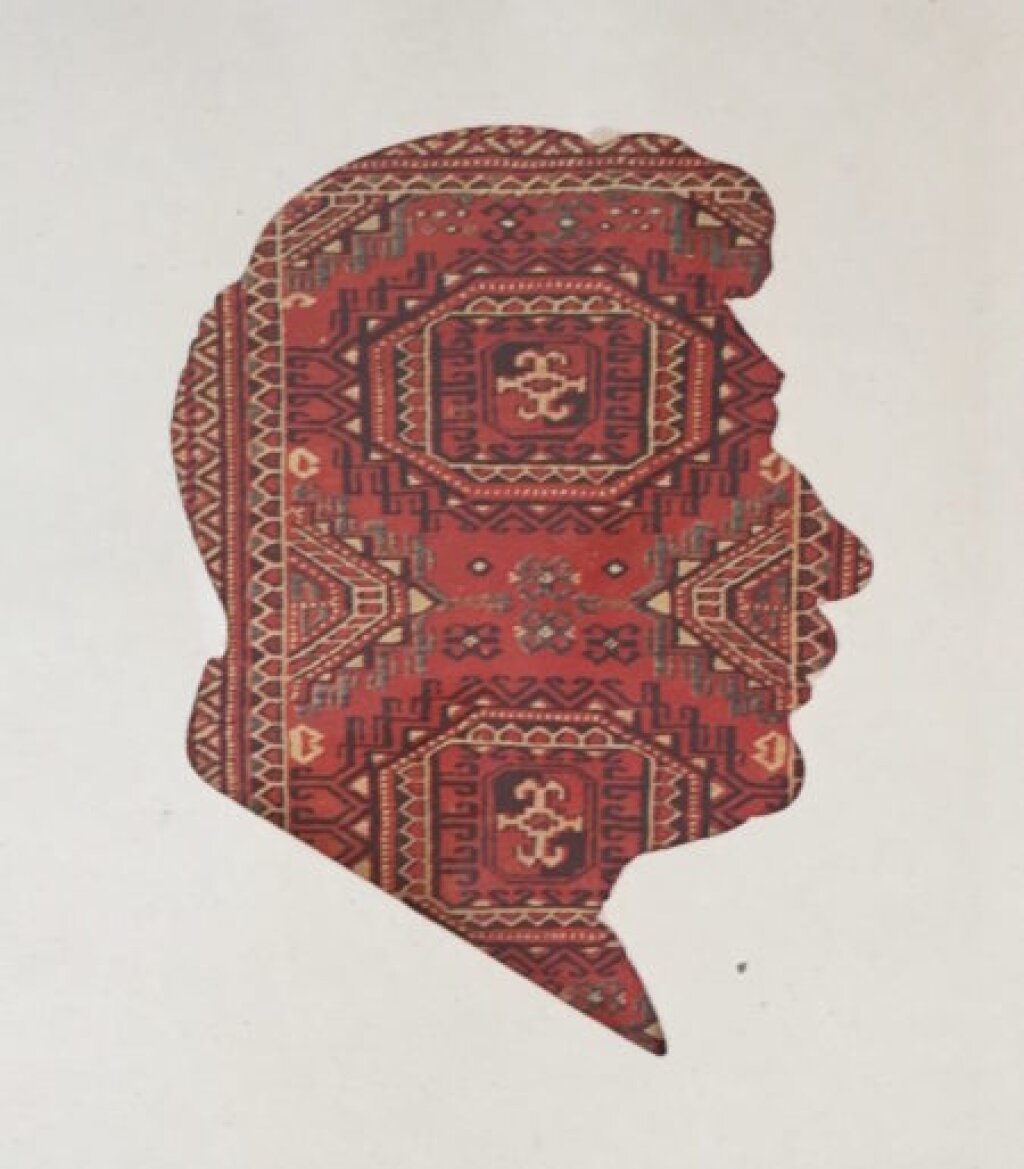

Professor Brintlinger's argument is developed along three ideas: Russian ideas about food become heightened during times of war and conflict; specific foods embody meaning beyond their sustenance value, to include national pride; and certain foods, such as potatoes, kvas and shchi, harken back to Russia’s peasant roots. The party scene confrontation in “I Am Twenty” juxtaposes the light atmosphere of the early 1960s youth culture— including French music and jazz, a fashion show and popular dancing—with the anti-urban utopia, a “true” Russia, and the world of potatoes, bast shoes and folk songs. “All we need now is Gypsies and bears,” one party guest quips.

Echoing research by Nancy Ries, the film “I Am Twenty” recognizes that potatoes saved lives in World War Two. The film was the creation of the late Georgian-born Soviet filmmaker Marlen Khutsiev, who died this year, aged 93. In its original form, “Ilyich’s Gate,” the film could not pass Soviet censors. An edited form was released four years later as “I Am Twenty.” “In my view, ‘I Am Twenty’ is still a great film, and when I showed it to my Russian Food and Cuisine students last semester, it brought up, for me, many of the usual Russian problems: fathers and sons, who is to blame, what is to be done,” said Dr. Brintlinger, who is a professor of Russian literature and Graduate Studies Chair at The Ohio State University’s Department of Slavic and East European Languages and Culture. Kvas patriotism in the context of “I Am Twenty” is an insult. “Khutsiev portrays them as self-sufficient Russian or Soviet patriots. The accusation flung at Sergei at the party does not stick. He is no false patriot,” Dr. Brintlinger said.

The origin of the term Kvas patriotism is in Napoleon’s invasion of Russia. The term’s first use can be traced to an 1827 letter addressed from Paris by Russian poet Petr Viazemskii. Viazemskii defines patriotism as “unqualified praise of everything that is your own,” and links it to French economist A. R. J. Turgot’s term “servant patriotism,” or du patriotism d’antichambre.

A recent example of “servant patriotism” was in the 2019 film “Downton Abbey,” when Downton staff sabotaged efforts by the official servants of visiting Royals so the domestic staff have the privilege of serving their own cooking to the King and Queen, Dr. Brintlinger said.

It is Viazemskii, a war veteran himself, who moves “servant patriotism” into the dining room by invoking kvas. He also suggested that the definition may include false or jingoistic patriotic feelings since serving kvas in an aristocratic dining room was not authentic. And a peasant drinking kvas to quench thirst was not contemplating patriotism. Earlier examples of praise for simple Russian life and values of hospitality and local foods are apparent in the work of 18th century poet Gavriil Derzhavin, such as “Invitation to Dinner” (1795) or “To Eugene, Life at Zvanka” (1807). A later example would be the Stalin-era Book of Tasty and Healthy Food, or products depicted in “socialist photorealism,” a term of essayists and food writers Petr Vail and Aleksandr Genis.

“We see even more pride and self-sufficiency today as Russians scramble to deal with the results of the renewed Cold War—those hated sanctions which have forced Russians to celebrate their own food production yet again,” Dr. Brintlinger said. “Forced—and perhaps enabled—to turn inward.” In “The Captain’s Daughter” and “Eugene Onegin,” Pushkin also mentions kvas in a positive light, and discusses things Russian and foreign.

In conclusion, Dr. Brintlinger discussed the significance of the antonovka apple, a beloved variety of the fruit whose features were documented as early as 1848 in a fruit grower’s handbook. The variety is particularly well suited for Russia’s climate. But this alone fails to explain Russians’ preference for the variety. One explanation is the “gastronomic and auditory nostalgia” identified by Svetlana Boym.

In another scene from “I Am Twenty,” apples fall and spread out across the pavement. One of the three friends at the focus of the film, Kolia, picks one up and uses it as payment for his tram fare, to the delight of the female fare collector. “Kvas patriotism may have a negative connotation—false patriotism, the ostentatious touting of ‘our own’ at specific political moments. But the antonovka apple, like kvas and potatoes, like shchi da kasha, has a historical resonance that signifies Russianness even for those who no longer live in Russia,” Dr. Brintlinger said.

In the Q&A, Bruce Grant asked about intended differences between patriotism and nationalism in this context, when patriotism, by definition, works inclusively, while nationalism, by practice, works exclusively. Most examples presented in the lecture were patriotic ones, Grant noted.

Professor Anne Lounsbery said a cross-cultural comparison of tropes of patriotism and localness was useful: at the time of Derzhavin’s writing, Alexander Pope was singing praises of English country houses and foods, for example. She also pointed out a real-life example of kvas patriotism was the Moscow restaurant White Rabbit, with Chef Vladimir Mukhin, and represented a trend of elevating traditional foods.

Dr. Brintlinger’s interest in food was in part inspired by learning to cook in her dorm in the Leningrad of the late 1980s. She recalls fondly her roommates who received crates of potatoes and garlic from far-flung places such as Novosibirsk and a village west of the Ural Mountains. The young women returned the kindness by sending parcels of hard-to-find clothing from Leningrad to their hometowns. It was there Dr. Brintlinger learned tips such as the practice of adding butter to soup to increase its calorie count, and about the joy of finding food to buy when store shelves were empty. These personal experiences helped inform Dr. Brintlinger’s other work on food in Russian literature, film and culture: an annotated translation of Russian Cuisine in Exile, a collection of essays and recipes by Vail and Genis, originally written in the mid-1980s. She also co-edited Seasoned Socialism, in which she examines cabbage as a “multivalent and gendered symbol of nourishment, national pride, folk wisdom and family.”