Maria Vinogradova is a film scholar and a Writer in Residence at NYU's Jordan Center.

On April 11-14, NYU’s Orphan Film Symposium returns to New York for the first time in six years. This biennial event, which gathers a diverse international group of scholars, archivists, curators, filmmakers, and artists, has gained a cult status among enthusiasts of rare and archival films. Expanding the definition of cinema beyond the body of traditional theatrical features, it turns towards the ephemeral and forgotten — including educational, industrial, science, amateur and local films. By projecting non-traditional audiovisual objects on the screens of major film institutions like the Museum of the Moving Image, Orphans (as the symposium is affectionately known) draws public attention to materials that never enjoyed the kind of prestige and visibility these institutions were built to celebrate and preserve.

This year’s Orphans features three films from the former Soviet Union, each highlighting the legacy of amateur movements in late-socialist cinema and culture. On Thursday, April 12, Eva Näripea, the director of the Film Archives at the National Archives of Estonia, will present A Sentimental Short Story (1966), an obscure 16mm film by the renowned Estonian cinematographer and still photographer Peeter Tooming.

On Saturday, April 14, an entire section of the Symposium’s program entitled Love Thy Neighbor: Music, Peace, and Friendship Across Borders, of which this post's author is proud to be a part, will focus on Leningrad in the 1970s and 80s. During the program's first part, the New-York based non-profit group XFR Collective — dedicated to preserving and disseminating at-risk audiovisual media — will present excerpts from the VHS film Thirty Days in One-Storied America, which it preserved and digitized a few months ago. Completed in Leningrad in 1989, the film was recently rediscovered in the archives of Surry Arts at the Barn, a community organization in Surry, Maine. At the height of perestroika, its amateur opera company engaged in a number of exchange projects with the Soviet Union, visiting the country three times, and in 1988 it received a visit from an association of amateur music collectives jointly named Leningrad Amateur Opera, accompanied by a four-piece crew of an independent television group Lira that documented the trip on video, resulting in the creation of Thirty Days.

Thirty Days in One-Storied America

(1989). The image's poor quality highlights the fragility of VHS video and makes plain the urgency of preserving similar media objects.In the second part of the section, I will present a work from Leningrad's amateur film studio called Creativity Is Creativity (1973). The majority of the film's participants were students from the city’s vocational schools, all learning working-class occupations. This 11-minute film is based on footage shot during a concert tour of Scandinavian countries by another working youth collective, the Smirnov accordion (or, more precisely, bayan) orchestra. Whereas the orchestra itself is still going strong today, the film studio once known as “the most professional among Leningrad’s amateur film collectives” ceased to exist along with the Soviet Union. With a few exceptions, its films, all dating to the 1960s, are currently believed to be lost.

Together, Sentimental Short Story, Thirty Days, and Creativity give insight into the peculiar phenomenon of Soviet amateur art. In a future post, I will discuss the complex relationships among ideology, cultural policy, and social realities within a system that allocated substantial material resources to their development. For now, suffice to say that amateur arts were more diverse than their most stereotypical exemplars (such as loosely affiliated groups of collective farmers performing an elaborately choreographed celebration of Soviet power). At their best, amateur theater groups, music ensembles and film studios engaged with experimental forms that exploited their limitations — in training, resources, and leisure time — to create original art. “Experimental,” meanwhile, did not necessarily mean "dissident" or "subversive," since this culture’s dialogue with state ideology developed within the spectrum of political attitudes that anthropologist Alexei Yurchak deployed in his analysis of “the last Soviet generation.”

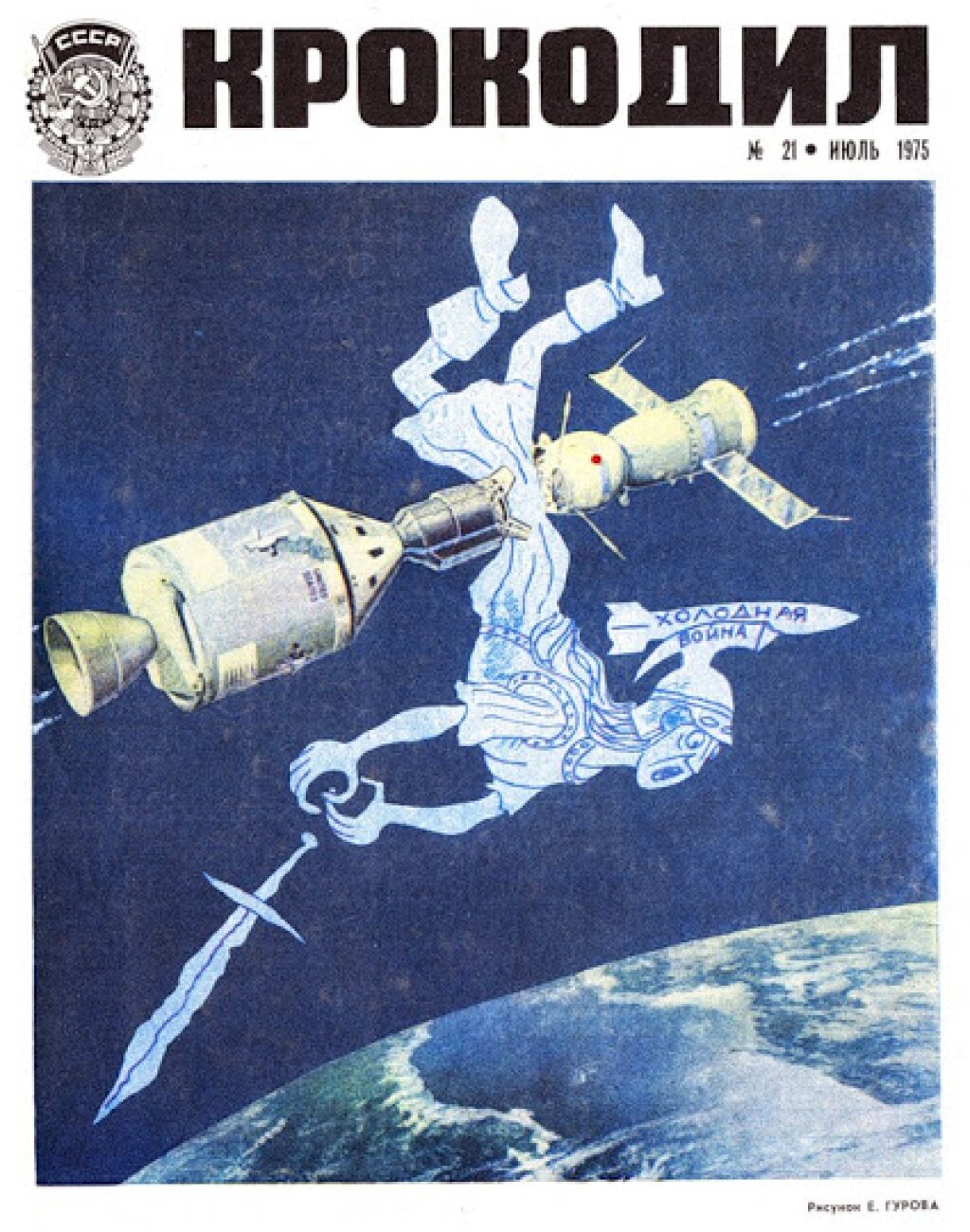

The two films highlighting Leningrad’s amateur music scene, Creativity Is Creativity and Thirty Days in One-Storied America, present another aspect in the lives of prominent amateur arts collectives — namely, foreign travel, a privilege inaccessible to most Soviet citizens. Early in Thirty Days, its voiceover narrator remarks that “you can’t really impress anyone these days by traveling abroad" — despite the fact that, in 1989, foreign travel remained a novelty for many people. By downplaying the extraordinariness of this experience, the film staked its claim on a new era — one that would permit Soviet people to be citizens of the world, just like their counterparts in the capitalist West.

Creativity Is Creativity, though vastly different in tone and period (it was completed in 1973), makes a similar claim. Anyone who experienced life in the Soviet Union or another Eastern Bloc country during this time remembers the fetishistic longing for material objects abundant in the West. The traces of this longing are carefully disguised in both films, which stress cultural connection and parity of dialogue over another type of curiosity evidently deemed too embarrassing to admit: the painful desire to experience the lives of those fascinating others living abroad.

Creativity is Creativity

(1973)This brief sampling of cultural cues merely scratches the surface of possible readings (I delve more deeply into these phenomena in this article on another Soviet amateur film). The rich meanings gleaned through such reading between the lines adds to the genuine cinematic pleasure of watching films like Creativity Is Creativity or the Estonian Sentimental Short Story. Beautifully shot and skillfully edited, they present evidence of a vibrant parallel film culture remains largely unknown.

A Sentimental Short Story

(1966)The archival status of Soviet amateur films is a troubled issue. If, in Estonia, recent preservation efforts on the part of the National Archives signal a change in attitude toward amateur creations, Russian amateur films mainly survive in small private collections. For a country with a major film culture and heritage, Russia has been consistently underrepresented within initiatives like the Orphan Film Symposium. Such initiatives push the definition of “unseen cinema” beyond unknown films created by well-known directors – the line that Gosfilmofond’s own archival film festival, Belye Stolby, is usually reluctant to cross, for multiple reasons. In a setting where even major institutions dedicated to the preservation and dissemination of Russia's national film heritage, such as the Museum of Cinema and Gosfilmofond itself are in crisis, “broadening horizons” to include non-canonical, ephemeral audiovisual objects can seem like a long shot.

The provenance of physical copies of films like Creativity accordingly becomes the stuff of detective stories. A 16mm copy of this particular film was generously provided by Daniil Zheherun, a dedicated enthusiast who keeps the remnants of the film library of the former Moscow Amateur Film Club in an impeccable condition — entirely on a volunteer basis, and under constant threat of eviction from the club’s basement, where the collection is stored.

This week, New York audiences have the unique opportunity to view these rare gems on the big screen.