Alex Houk is an NYU graduate and former Fulbright English Teaching Assistant.

Okxana Cordova-Hoyos is a former Peace Corps Health Education Volunteer and current MPH candidate at the University of Pittsburgh.

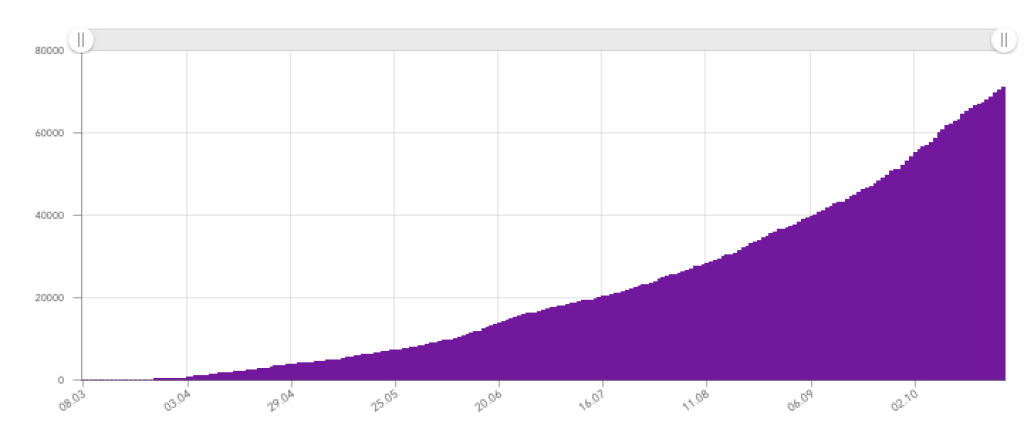

Since school began this fall, we have seen a rise in coronavirus cases around the world where classes are held in person. Moldova is no exception, with cases slowly but steadily climbing since the beginning of the pandemic. As former educators in Moldova, we were interested to see how the pandemic has been affecting our former colleagues and students.

In March, schools abruptly shifted to remote education. As Viorica Condrat, one of Alex’s former colleagues, put it, “The traditional classroom vanished into thin air one day, leaving teachers and students alike in the dark.” This speaks to the uncertain climate we all have experienced, questioning what the future may hold, as well as the specific struggle of adapting to remote education.

Even in the US, where teachers and students regularly use technology in the classroom, the switch to online learning was hardly smooth. Access to technology and the Internet are issues the US and Moldova share, although they have manifested quite differently. For example, the Internet infrastructure in Moldova is particularly good when compared to the United States. When ranked by percentage of population with access to high-speed Internet, Moldova ranks fifth out of the 61 countries listed on Gigabit Monitor with 90% coverage. Meanwhile, the US is ranked 26th with 25% population coverage.

Despite the good infrastructure, there are other factors widening the digital divide in Moldova. The teachers we interviewed spoke about the cost of Internet plans relative to salaries, low access to devices such as laptops and tablets, and a lack of teachers’ and students’ digital literacy skills, which are crucial for online learning. Even if a family has access to the Internet and an appropriate device, it is a common struggle to have too few devices for all their children. A survey conducted earlier this year on the reactions of teachers in Moldova and Romania to online learning confirms these views.

The Moldovan Ministry of Education and other organizations, including private companies, tried to ease the transition. Major Internet providers Orange, Moldcell, and Moldtelecom partnered with the Ministry to offer 50 GB of free data to teachers in the spring. This was a short-term solution, however, and the cost of increased Internet usage now primarily falls on teachers. Some schools have installed Wi-Fi in order to give their staff a place to work, but many schools do not have sufficient resources to do so.

The Ministry of Education created several resources, including a master list of recommended remote education technologies, but overall the guidelines provided were uncharacteristically loose. Some teachers remarked that their complete unfamiliarity with the recommended technologies made the decision of which to use very difficult. Some wished that the government guidelines could have been tightened somewhat by their own school or institution because using the same platforms could have enabled staff to better help one another during the transition.

School health regulations at the national level are likewise relatively loose. Individual schools or towns are able to add to the regulations as they see fit. Schools were allowed to return to in-person learning at the beginning of the fall semester and many have done so. Some national regulations include requiring that teachers wear masks at all times, that students wear masks in the hallways, and that students remain at least one meter apart. Ways of meeting these regulations varies from school to school. Some schools split their students into two groups, alternating online and in-person attendance; others have students come in two separate shifts; and some schools which are large enough to accommodate the one meter distance between students are operating at full capacity.

The national guidelines are not only loose with respect to previous educational policies but are also loose with respect to public health policies when the shutdown originally began. For instance, very high fines have been levied against businesses and individuals who violate any of the coronavirus restrictions on public space. These fines came as a shock to many as they can amount to many months of an individual’s salary. Some legislation has recently been proposed to reduce them.

These mixed signals, including fluctuation between strict and lax regulations, are one factor in the public’s mixed feelings on the virus. In the United States, our political climate has had a strong impact on public attitudes toward COVID-19. In Moldova, a similarly polarized political climate shapes people’s attitudes in the lead-up to the presidential elections on Sunday, November 1. Current president Igor Dodon promises access to the Russian COVID-19 vaccine will begin soon, which points to the strong role pandemic policy plays in the election.

Regardless of the election's outcome, the mixed views on coronavirus pandemic policy will continue to affect the entire public, especially teachers and students. In the words of Aliona Popa, one of Okxana’s former colleagues, “Teachers feel very alone and wish there was an effort made on all parts,” including students’ families and the community at large. “At times, it feels very one-sided and we wish we had more help.”