Brianna Philpot is a graduate of NYU's program in Russian & Slavic Studies and International Relations. She is Editorial Assistant for All the Russias.

This is Part I of a three-part series. Part II will appear tomorrow, 8/26 and Part III on Friday, 8/27.

Russian interference campaigns do not discriminate. They target the left as well as the right. But with right-wing violence the largest terrorist threat facing the US today, the potential impact of Russian interference on far-right targets is a pressing issue for US policymakers. The combination of disinformation, conspiracy theories, and extremist groups is a recipe for violent disaster.

Part I: Disinformation

The 2016 US presidential election cycle brought concerns about Russian interference in US domestic politics to the forefront of public notice. The Intelligence Community (IC) later concluded that “Russia’s goals were to undermine public faith in the US democratic process.” Using a “collection of official, proxy, and unattributed communication channels and platforms,” Russia exploited fissures in American society by “amplifying divisive social and political messages across the ideological spectrum.”

This asymmetric approach to foreign policy, or New Generation Warfare, has been the favored technique of the Putin regime, with roots in the Soviet Union’s active measures. Although the IC assesses that Vladimir Putin himself “ordered an influence campaign in 2016 aimed at the US presidential election,” not all directives come from the top. Instead, the administration transmits “opaque signals” to its allies within and outside of government. It is up to allies to decipher these signals and transform them into practicable policies and decisions. Such an indirect approach gives the regime plausible deniability in the event of failure or backlash.

A new era of sophisticated disinformation is around the corner as advanced digital tools become increasingly available to individuals and state actors alike. Deepfakes, which allow users to create realistic video and audio with the help of artificial intelligence, are already starting new internet trends. Although they can be easy to detect (for now), they can also be persuasive, and they’re not the only AI programs that can fool humans. Automated text programs, for example, generate text that appears credible at first glance, expounding at length on the topic (and in the style) of the creator's choice.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sbFHhpYU15w[/embed]

Above: A deepfake made by representUs that depicts Russian President Vladimir Putin giving an address in English

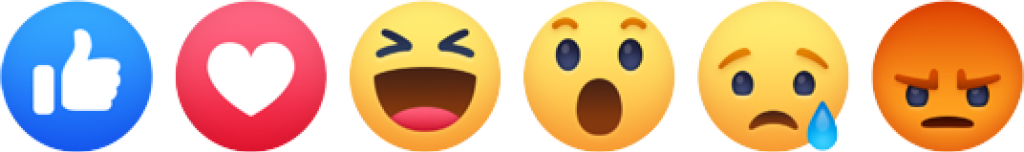

As these tools become more advanced and available, the ability to reach vulnerable internet users is also increasing. The introduction of “reactions” on Facebook in 2016 has commodified information about not only which pieces of content users engage with on the platform, but how it makes them feel.

Third parties, including Russia, will be able to use this information to micro-target individuals with custom designed “content meant to incite an emotional response.” The combination of artificial intelligence and personal data will make not only for targeted advertising but also compelling interference campaigns that reach susceptible targets and degrade the information space.

Above: Facebook's "reactions," introduced in 2016

And when artificial intelligence won’t do, there’s always the real thing. Russia has begun to outsource its propaganda efforts to legitimate journalists and writers, a throwback to Soviet-era tactics which will likely expand to include regular social media users. Meanwhile, the Covid-19 pandemic has threatened the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of workers across the globe, leaving them vulnerable to recruitment and exploitation.

Those who fall prey to Russian schemes by renting out their accounts and facilitating Russian disinformation campaigns raise difficult questions about the First Amendment and make regulation even more difficult. Twitter’s reluctance to unmask anonymous users who violate their policies on the grounds of protecting free speech indicates that accusations of censorship are likely to continue influencing internal regulatory efforts. But with lawmakers divided and unable to pass legislation that addresses online disinformation, it falls to the social media platforms themselves to regulate content on their networks.

The piecemeal set of solutions they have deployed thus far are unlikely to be fully successful, and even the most effective solutions can’t catch everything. Fact-checking, Facebook’s favored response, has had limited success, still less in “polarized contexts” like our own. Another unfortunate vulnerability in open societies is that the speed at which content spreads online makes disinformation difficult to debunk before the damage is done.

Social media platforms, moreover, have little incentive to intervene in the spread of disinformation. The success of their business models hinges on algorithms that “prioritize engagement over truth.” Donald Trump, who had 88 million followers at the time of his permanent ban from Twitter, is a prime example of this phenomenon in action. Despite his repeated violations of the platform’s policies, Twitter waited until the eleventh hour—as many of his allies began to denounce him—to act. Some platforms, like Parler, trumpet their limited content restrictions as a selling point.

Above: Donald Trump tweets out misinformation about mail-in ballots in the lead up to the 2020 election

Russia has found a winning strategy in wading into contentious political discussions like those about Black Lives Matter (BLM) and vaccines. Tools like microtargeting enable disinformation campaigns that intentionally provoke anger and resentment. Last summer, for instance, Russian online operatives distorted reports that BLM protesters had burned Christian Bibles and the US flag, mobilizing the resulting outrage like a precision-guided weapon.

Deepfakes are an invaluable tool in this type of cyber-warfare. A deepfake portraying an incendiary incident, like a violent encounter between a white police officer and Black civilian, could stoke tensions that escape the confines of the internet to wreak havoc in the real world. The addition of seemingly authentic bots and other purveyors of disinformation to increase the volume of online discussion lends the relevant discourse undeserved legitimacy, making it appear more contentious than it actually is.

As these campaigns undermine the integrity of public discussion, trust in the media is likely to continue to decline as well. Given the polarized nature of political discourse in the US, many Americans are likely to take dubious trustworthiness of the information they encounter on a daily basis as tacit permission to believe what they wish. As it stands, the perceived legitimacy of a source has little bearing on the likelihood that social media users will share it, a golden opportunity for purveyors of disinformation to spread their desired message far and wide.