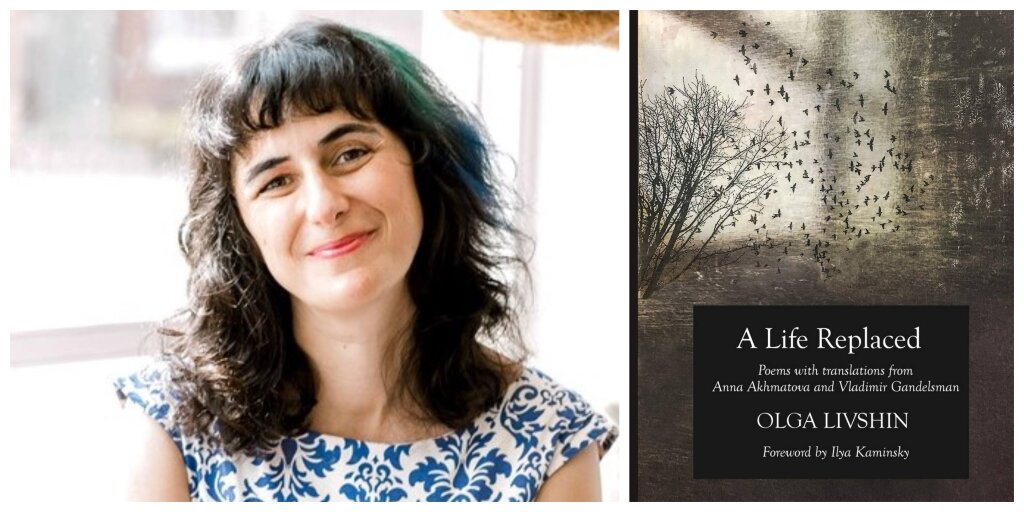

On October 16, 2020, the Jordan Center hosted Olga Livshin, an English-language poet of Jewish descent, via Russia and Ukraine. Livshin began by introducing and reading excerpts from her recently published A Life Replaced: Poems with Translations from Anna Akhmatova and Vladimir Gandelsman (2019). She then joined Professor Eliot Borenstein to discuss the challenges of finding the right words for transnational ties to her home countries after the 2016 election as a poet and translator.

It is not a coincidence that Livshin started to compile poems for her book in the US election year of 2016. “It is one of those projects you know you’ll have to do someday; and then you realize that you’ll have to do it soon—because the voices, such as yours, are not exactly being represented,” said Livshin, setting the tone for her experience as a minority writer caught in many worlds.

For Livshin, that immigrants from the former Soviet space are being treated as a “topic”—objects rather than speaking subjects—was the norm long preceding the advent of Trump. “How is it that there is this cultural ‘other’, who is not really an ‘other’ because the ‘other’ is assimilated? And what do we sound like when we speak?” she asked, continuing Gary Shteyngart’s questions in Absurdistan.

Livshin used a triangle to sum up the American mainstream narratives of the post-Soviet minorities. On the one hand, Russians are conflated with the Russian state (and later, the Slavic languages, history, and culture), perceived as Putin’s long arm extending into the US. Livshin remarked that even liberal discourses actively try to solicit an answer from her and her friends: “What happened? How could [you people] possibly like Trump?” She added that this is, of course, in the midst of expats, immigrants, and journalists being banished and repressed by the same Russian state that they deemed so loyal to by the American imagination.

“In a dark and comical way, I get buttonholed at different meetings I went to,” said Livshin, “but there is not a particular technology installed in my brain to speak about what happened [or] how Russians interfered [in the election].”

On the other hand, the immigrant experiences are often seen by the Western states as always associated with seeking refuge. “It is the ritual that we have to talk about — ‘How were things?’ ‘And, how are things now?’ ‘Are things better?’” said Livshin, recalling migrating to San Diego as a teenager herself. She then cited a passage from Iranian-American-French author Dina Nayeri’s memoir, which teased out the ways in which the Western audience fetishizes immigrant testimonies of escaping authoritarian regimes: “[...]they wanted our salvation story as a talisman, no more.”

Livshin thus strives to restore the intricate layers of the past that immigrant subjects are so often denied the access of — where do they come from, and who their ancestors are.

“I used to be a Russian immigrant who spoke Russian with my family at home and wrote poems in Russian,” said Livshin, “that [writing] was the way to maintain my identity.” She added that while every immigrant family is different, the first few years one is told about their family and culture are very tenacious in their life.

Her book A Life Replaced captures exactly the kind of triangle as described by Livshin herself — except that she is also in conversation with her poetic ancestors (Anna Akhmatova) and contemporaries (Vladimir Gandelsman). She stressed that it was an exciting project for her to help the speechless immigrant find new voices. Instead of playing the traditional role as a “semi-assimilated translator,” she creates an ecstatic space for a “Russian fiesta.”

Livshin then proceeded to poetry reading, followed by Q&A on topics such as the role of English translation, multiculturalism, and borderlands.