Elena Pedigo Clark received an MA from Columbia University and a PhD from UNC-Chapel Hill. She is currently an Assistant Professor of Russian at Wake Forest University.

Logan Stinson received a BA, with Honors, in Russian, Summa Cum Laude, from Wake Forest University and is currently a healthcare investor at Great Point Partners, a Greenwich, CT-based private equity fund.

This post is a shortened version of an article that originally appeared in Slovo in 2018. It is based on research for Elena Clark's book Trauma and Truth: Russian Literature on the Chechen Wars, forthcoming from Academic Studies Press.

In literature and in real life, there is a new type of veteran. From the West’s GWOT (Global War on Terror) "hitters" to the generation Russia lost to Chechnya, the days of victory parades, shared belief and struggle, and the romanticized idea of the "War Hero" or "Veteran" is gone. This is reflected in modern war literature, as veterans of these recent wars attempt to tell their truth to what they frequently perceive to be an indifferent or hostile audience back home, and bridge a gap they themselves often claim to be unbridgeable.

This new war literature is non-linear, inwardly directed, and contains multiple points of view. Its authors often subvert the tropes of the war story, and seem primarily concerned with making an emotional connection with their readers and describing what their war was like. While in the past few years a growing number of English-language works have come out that exemplify this trend, some of the first examples of this fragmented, impressionistic, and emotionally intense war writing were produced in Russia.

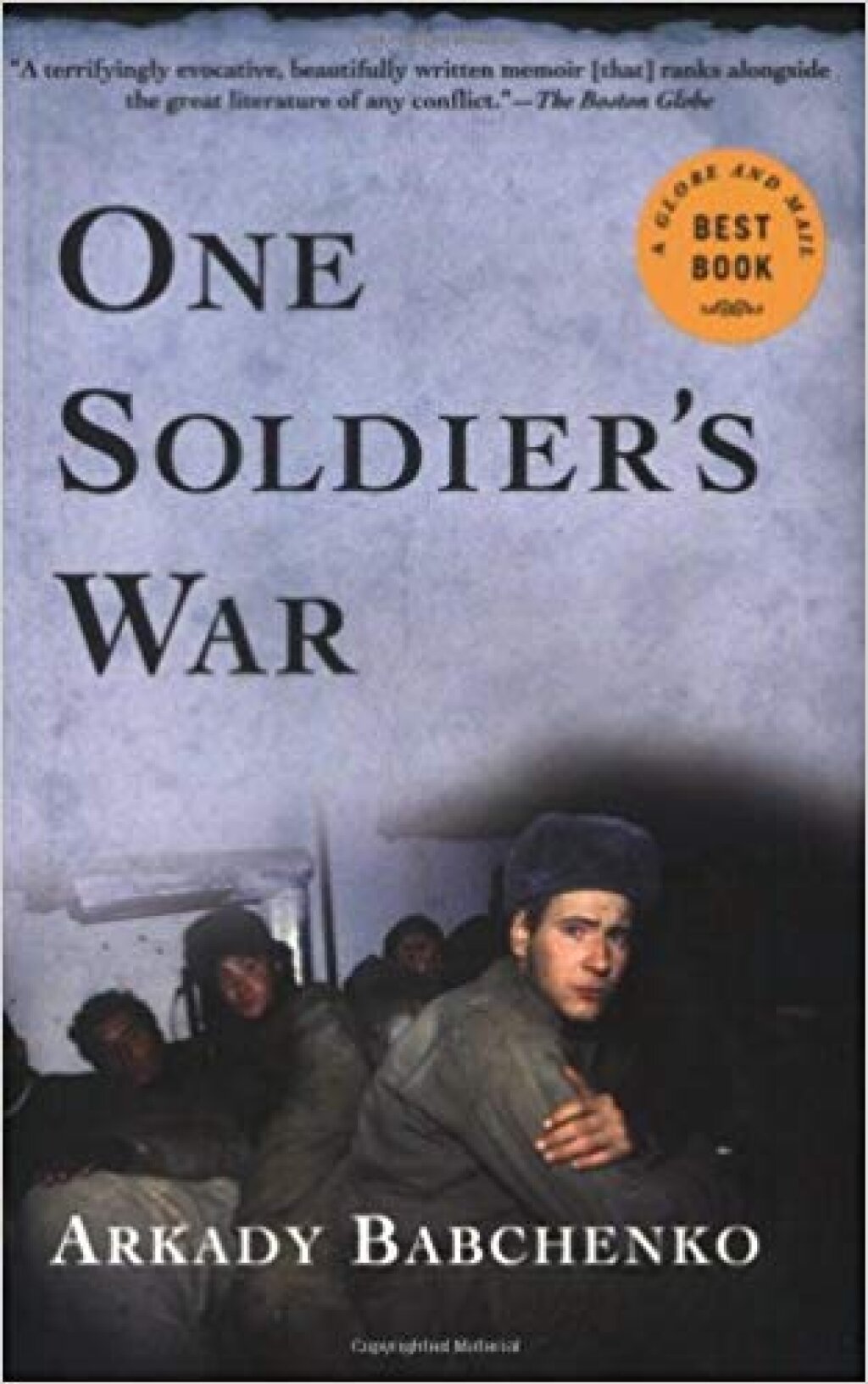

One of the earliest, most controversial, and most widely hailed works is Arkady Babchenko’s One Soldier’s War, a collection of stories about his two tours of duty in Chechnya. Babchenko recently made headlines again, first when he fled Russia following a particularly abrasive Facebook post, and then with his dramatic “death” and resurrection in 2018 as part of a sting operation to uncover an alleged Russian assassination plot. The irony that, having risked his life in Chechnya, Babchenko had to fear assassination from the government he strove to serve, could be seen as a tangible example of veterans’ confusion when they return home, especially from distant and intangible conflicts such Chechnya and Afghanistan.

Paradoxically, given that emotional connection seems to be driving goal behind this new war literature, one of its main unifying themes is the sense of isolation from civilian society. Academics and soldiers alike warn of the increasing disconnect between soldiers and the civilian populace: as American veteran and author Brian Van Reet says, in the US we now have a "samurai class that fights the wars." This has led to ambiguity in the civilian-military relationship in these countries, and fuels the contradictory theme of much of current war writing, in which veteran-authors seek to present themselves as the bearers of a special insight unattainable to those who have not experienced combat, while also trying to convey the truth of what they experienced, often in highly emotional terms.

These emotional truths, which are based on unique personal experiences, can separate veterans even from each other. The distance between veterans of Chechnya can be seen on a physical level in the current conflict in the Donbass. Babchenko, for example, has received death threats from fellow veterans after taking a very public stance against the separatists there. Meanwhile, his fellow veteran-writer and former colleague in Novaya Gazeta Zakhar Prilepin has taken an active part in the conflict as part of a separatist battalion, and the two engage in frequent skirmishes on social media.

The inability of veterans to connect even with each other is brought home in the final story of One Soldier’s War, "I Am a Reminder." In it Babchenko interviews a crippled veteran who now begs at a subway station near his apartment in Moscow. Babchenko’s interviewee is so caught up in his own rage and pain that he is unable to reciprocate the understanding that Babchenko tries to extend to him. The intense experiences the soldiers had in the war, allowing them to feel that they were tied together with inseparable bonds of brotherhood, no longer function in civilian life, and not only can they not forge connections with civilians, but they cannot forge connections with each other, either, not as they could during the war.

Furthermore, they are cut off from the truth as well. One Soldier’s War is an attempt to convey the truth of the soldiers’ experiences in Chechnya to those who lack the knowledge to understand what war is truly like. It is ‘one soldier’s war’, but it is ‘every soldier’s war’ as well. Those who participated in the war received, in return for all that they gave up, the true knowledge of war and of themselves.

But that, it turns out, was all temporary and conditional. The story, and the entire book, ends on a melancholy note, admitting defeat in its main aim of sharing the story of the war:

"Half-truths everywhere, half-sincerity, half-friendship. I can’t accept that. Here in civilian life they have only half-truths. And the small measure of truth we had in war was a big lie. So many boys died and I survived. The whole time I used to wonder what for. They were better than I was, but I survived. Surely this not pure chance. Maybe I lived so that others remember us? I am a reminder," he says with another evil-sounding laugh.

I get up silently and leave him cigarettes, matches and vodka. There’s nothing else I can give him apart from money. I walk away without saying anything and he doesn’t even look at me. For him I am also ‘one of them.’ Which means whatever I say is a half-truth. (395)

The writers of modern war literature position themselves as witnesses to something that the rest of the world wishes to ignore. They are primarily concerned with telling the truth, which tends to turn into their truth. The result is often fragmented, non-linear, highly emotional literature that dwells on the protagonist’s experiences of fear and psychic disintegration, something that is mapped out in the works’ structure as well as being described in its contents.

These works, of which One Soldier’s War is a prominent but by no means isolated example, attempt simultaneously to reach out to the reader and convey what the war was like, and to draw a line between the reader and the author, declaring that the reader will never be able to understand what the war was like.

This approach-avoidance dance between reader and author, along with intensely rendered inner states designed to elicit shock and sympathy in equal measure, is characteristic of the war writing coming out of these new conflicts that are increasingly being fought by a "samurai class" that feels itself cut off from the society it supposedly serves, and seeks to create connection where it can. Both the conflicts abroad and the problems they have revealed at home remain largely unresolved, putting readers, even those who supposedly can never understand, squarely in the middle of the issues these authors raise. How it will turn out has yet to be decided.