Sarah D. Phillips is Professor of Anthropology and Director of the Russian and East European Institute at Indiana University

How does a country fighting a war, in deep economic and political crisis, with a history of Soviet-era discrimination and abuse of people with disabilities, produce a world-class team of Paralympic athletes? This is exactly what has been accomplished by Ukraine, whose Paralympic team captured an astonishing third place at the 2016 Paralympic games in Rio de Janeiro, behind China (1st place) and Great Britain (2nd) and ahead of the United States (4th), Australia (5th) and Germany (6th). (Russia’s Paralympians were noticeably absent, having been banned from the 2016 games by the International Paralympic Committee for allegedly violating doping rules.)

A race to the top

The Paralympic games debuted in Rome in 1960, but Ukraine has only been competing in the Paralympics since the 1996 summer games in Atlanta, where the Ukrainian team placed 44th out of 60 national teams. The Ukrainian Paralympic team rose from 44th place in Atlanta to 3rd place in Rio in just 20 years, coming home from Brazil with 117 total medals (41 gold, 37 silver, 39 bronze), 22 new world records and 32 Paralympic records. (For contrast, in Rio the “regular” (non-Paralympic) Ukrainian Olympic team corralled only 11 medals and took 31st place.) Notable Ukrainian achievements in Rio’s Paralympics included swimmer Anna Stetsenko, who smashed a 20-year-old world record in the women’s 50m freestyle, S13 (visual impairment), and Dmytro Zalevsky, who set a new world standard in the men’s 100m backstroke, S11 (visual impairment).

Paralympics’ main man

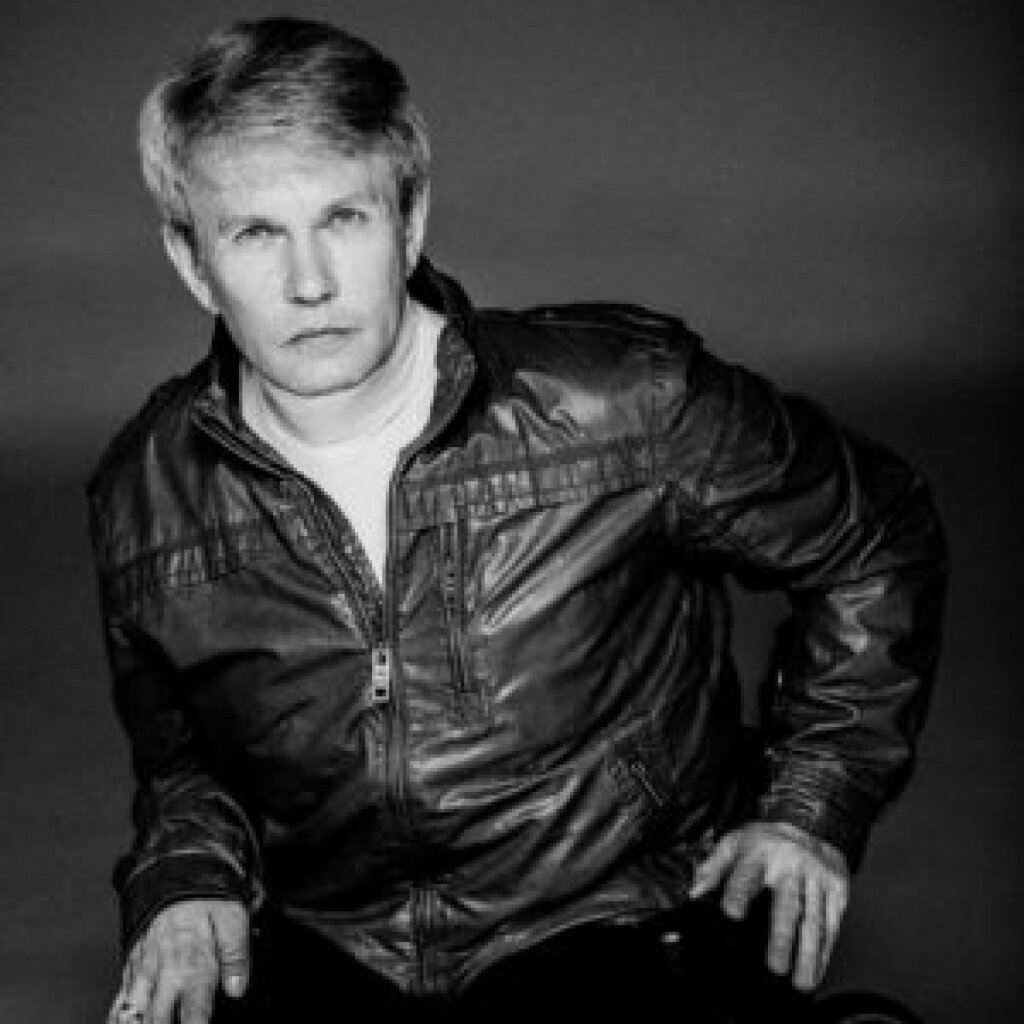

Much of the credit for Ukraine’s Paralympic triumph goes to one man: Valery Sushkevych, the founder, leader, curator, and enforcer of the Ukrainian Paralympic movement since its inception in the mid-1990s. Born in 1954, 62-year-old Sushkevych, who grew up in Dnipropetrovsk (then in the Ukrainian SSR), uses a wheelchair after surviving childhood polio. As Sushkevych told me during a 2005 interview, he was trained as an engineer but really “found himself” in sports: in Dnipropetrovsk he became a champion swimmer and founded a sports club where athletes with disabilities could train. Like many powerful politicians and oligarchs, including former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, Sushkevych came of age politically in Dnipropetrovsk, where he was elected to the regional Parliament in 1990. But he quickly made a name for himself in national politics in 1998 when he became the first person with a disability ever elected to Ukraine’s National Parliament.

Sushkevych served as the long-time Head of the National Committee for Sports of Invalids of Ukraine (called Invasport), head of the Ukrainian National Paralympic Committee, and also head of the State Committee for Pensioners’, Veterans’, and Invalids’ Affairs. In 2003 he founded (and still heads) the National Assembly of Invalids of Ukraine, a coalition of more than 100 disability rights NGOs in the country. In other words, wherever you run across disability issues in Ukraine, especially if sports are involved, you will also find Valeriy Sushkevych. No longer an MP, Sushkevych currently serves as Commissioner for the Rights of Disabled People in Ukraine. In this capacity he acts as a direct advisor to the President of Ukraine on disability issues.

A unique country-wide system

A second key component of Ukraine’s Paralympic leap has been the long-time existence of Invasport, a state-based network of athletic programs and facilities (many of them very modest) throughout the country, a system that Valeriy Sushkevych helped build. This system of programs boasts an array of sports federations—for the blind, for the deaf, for athletes with mobility disabilities, etc. Sushkevych characterizes this system as one of a “father” (the Ministry of Youth and Sports), a “mother” (the National Paralympic Committee) and a “child” (the Invasport system). In amateur sports, many people with disabilities enjoy valuable—and sometimes life-saving—opportunities for rehabilitation, exercise, and socialization, and a handful of these amateur athletes go on to more elite forms of sports, including Paralympics. Apart from sports, however, Ukrainians with disabilities are offered few opportunities to “realize themselves,” and only a few disabled athletes can climb to the heights of the Paralympians and other top-level competitors, who make a decent living from sports thanks to a state salary and prize money. And of course, athletic careers are very short careers, and when they’re over, elite athletes must seek out other means of survival.

Trouble in paradise

A pivotal moment in Ukrainian Paralympic history was the creation of the National Ukraina Center (sometimes called the National Paralympic Center), a multimillion-dollar sports complex that Valeriy Sushkevych and his son Sasha Sushkevych initiated in the early 2000s near the Crimean city of Evpatoria. The Ukraina Center was built primarily as a training facility for the Ukrainian Paralympic team, and for a time it was the only fully wheelchair-accessible hotel, sports facility, and beach in the entire former Soviet Union. For several years occasional Active Rehabilitation camps were held at the Center—Active Rehabilitation is a rehabilitation program for wheelchair users introduced in Eastern Europe by the Swedish advocacy group Rekryteringsgruppen. Since the early 1990s, week-long active rehabilitation camps teach new wheelchair users to navigate architectural and psychological barriers to foster long-term empowerment and independent living.

At the National Ukraina Center, active rehabilitation camps often were sponsored by the national Invasport, and the camps served as a training ground for selecting and coaching elite Paralympic athletes. In post-Rio interviews, Sushkevych claims that both the Chinese and the Brits (who, recall, took first and second place in overall medals at the Rio games) have copied aspects of Ukraine’s Invasport system and National Paralympic Center wholesale.

As I detailed in my 2011 book on the Ukrainian disability rights movement (Disability and Mobile Citizenship in Postsocialist Ukraine, Indiana University Press), the well-appointed National Ukraina Center has not been uncontroversial. Some disability activists characterized the facility as an elite luxury for the few: Why spend millions of dollars of government money on a world-class facility that benefits only a tiny fraction of disabled Ukrainians? As one critic put it, “With the resources that went into the Ukraina Center, they could have built adequate rehabilitation facilities in all of the country’s 26 regions and all the major cities!” Valeriy Sushkevych was also criticized for putting his son, Sasha, in charge of the Center; nay-sayers cried nepotism and corruption and accused the duo of using a quasi-state recreational complex for personal gain. The plot thickened further when the Russian Federation annexed Crimea in March 2014, effectively placing the “National Ukraina Center” squarely in Russia.

There is some confusion as to who owns the Center today, and who has the right to utilize it. The story circulates that the Center is now actually the “private property” of Sasha Sushkevych, not the Ukrainian state, and thus cannot be co-opted by the Russian Federation; sources tell me that Ukraine’s Paralympians continued their training uninterrupted in Evpatoria prior to the Rio games, and that active rehabilitation camps for people with disabilities from Ukraine continue there apace. But the official narrative states that the Ukrainian Paralympic team has not been able to train at the National Ukraina Center for some time; in post-Rio interviews Sushkevych and Paralympic athletes are lamenting “the loss of our Center,” presumably to Russia (and to the Russian Paralympic team). In any case, a new Ukrainian Paralympic Center oriented towards winter games already has been built in Modrychi in the Carpathian mountains, and plans are afoot for a new summer games Paralympic Center in Ukraine’s central region, to replace the “lost” Center in Evpatoria.

Again, Sushkevych

While navigating these troubled waters, Valeriy Sushkevych has firmly situated himself as the father of Ukrainian Paralympics and the key to the movement’s success. Here again he is not without critics. By many accounts Sushkevych demands absolute loyalty (some would say submission) from athletes, and I know extremely gifted athletes whose personality conflicts with Sushkevych kept them off the Paralympic team. Nonetheless, there is no doubt that Paralympics in the former Soviet Union has come a long way since 1980, when a Soviet official asked by a Western journalist about the USSR’s failure to participate in the Paralympic games reportedly insisted: “There are no invalids in the USSR!” Most agree that Ukraine’s steady Paralympic progress is in large part thanks to the tenacity, drive, and single-mindedness of one individual: Valeriy Sushkevych.

Cinderella comes home

Ukraine’s summer Paralympic team placed 6th in 2004, 4th in 2008, and again 4th in 2012, but the Ukrainian press and public seemed to barely take notice. This year feels different. Upon their return from Rio, the 2016 Paralympians were greeted by fans, family, and friends in the middle of the night at the Kyiv airport. The team’s success is being widely lauded in the Ukrainian and international press. Ukrainians abroad cite statistics from Ukraine’s stellar showing at the Rio Paralympic games. After the games the Chairman of the National Parliament, Andriy Parubiy, officially congratulated the Ukrainian Paralympians on their achievements in Rio and hailed their “triumphant” return.

Back to real life

But most of Ukraine’s disabled population lives a very different reality. The overwhelming majority of people with disabilities in Ukraine—some 2.7 million people, or 6% of the population—are not elite Paralympic athletes, or any kind of athlete. Many live in deep poverty, with only a paltry disability pension of around $55-80 a month for survival. And despite passing comprehensive legislation that guarantees people with disabilities equal rights in education and employment, an array of social supports, and equal accessibility to transport and the built environment, many children and adults with disabilities continue to face stigma and discrimination. They do not live in accessible environments,[1] do not enjoy equal opportunities for education, and cannot find jobs. Many live in poor health, lacking physical and economic access to quality health care.

Although Ukraine has ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (the United States has not), and a National Action Plan for implementation was passed in 2012, Ukrainians with disabilities enjoy far fewer privileges than their counterparts in the U.S. and in other European countries. Soviet practice was to warehouse the disabled and keep them out of sight, and out of “healthy” society. In 2008 it was estimated that 38,000 people with disabilities in Ukraine—children and adults—were still living in residential institutions. Doctors continue to encourage parents who give birth to children with serious disabilities to place them in institutional care. Thankfully, some parents’ groups are developing alternatives to the institutionalization of disabled children through family and community supports, such as the Dzherelo educational and rehabilitation center in L’viv.

Paralympics, war and politics

Obviously, in 2016 there is a huge crevasse between the visibility of Ukraine’s successful Paralympians and the invisibility of most people with disabilities in the country. And the ranks of those with serious disabilities is steadily growing, as scores of Ukrainian soldiers and volunteers return from the war with spinal injuries, amputations, brain injuries, PTSD, etc. The Ukrainian state’s response to this influx of disabled veterans has been entirely disappointing, and it is left to civic organizations and private donors to assist wounded vets with medical care, prosthetics, and other necessities. During the Rio games several Ukrainian Paralympians claimed Ukraine’s Paralympic victory as a national victory in wartime, and a group of men wearing fatigues, presumably soldiers in the Donbas conflict was at the team’s welcome-back fete in Kyiv.

This framing may spark important national conversations about the war, disability, and disability rights. In a recent interview on Ukrainian television, gold medalist Andriy Demchuk (wheelchair fencing) spoke of the Paralympic team’s plans to lend encouragement and support to Ukraine’s recent war wounded. Such an intervention could bring much-needed attention to ongoing problems in medical care and rehabilitation for Ukraine’s disabled population, including the war wounded. It is incumbent upon Demchuk and his fellow Paralympians to keep the national spotlight shining on disability issues. Hopefully Ukraine’s Paralympians, who have achieved so much, will return to their own communities as visible and energetic ambassadors for disability issues.

Ride the wave!

It is also critical that the disability rights movement in Ukraine find ways to ride the Paralympic wave of success. The Paralympic fervor can lend much needed energy to the fight for equal rights and recognition for all people in Ukraine with disabilities. Disability activists should continue advocating for accessible transport, architecture, and facilities of all types—including but not only those for rehabilitation and sports. They need to capitalize on the current public visibility of people who are “different”—Paralympic athletes who are wheelchair users, amputees, blind, deaf, etc.—to argue for the beauty and value of the range of human variation, and to underscore the dignity and abilities of every diverse human being. Hopefully, media outlets will tell the story not only of Valeriy Sushkevych, who already garners robust press coverage, but also the stories of individual Paralympians.[2] It is important to acquaint “regular people” in Ukraine with “real live disabled people” through first-person, experience-near narratives, an intervention I have argued is critical to the fight for equal rights in Ukraine.

As one seasoned disability rights activist, Yaroslav Hrybalskyy, recently told me, “Sushkevych was able to bring attention to disability issues through the Paralympics. He’s used the Paralympic athletes as examples, to draw society’s attention, and then to continue the fight in different ways.” In Sushkevych’s own words: “Our Paralympic team wants to prove to Ukrainian society, and the Ukrainian government, that people with disabilities can be full-fledged citizens of this country.” It appears that Sushkevych’s long-term goals could come to fruition, but only if the country’s Paralympic success in Rio is leveraged to produce more respect, more recognition, and more equal rights for the millions of people living with disabilities in Ukraine today.

Photo Credits

Photos reproduced with the permission of Euromaidan Press.

Notes

[1] This video of a stuntman “protesting ramps for the disabled” in Ukraine has gone viral: http://uainfo.org/blognews/1474354625-slabonervnym-ne-smotret-kaskader-protestiroval-pandusy.html In fact these are not wheelchair ramps (they are used for roller bags) and wheelchair users would not try to use them. But the stuntman’s point is made: people with mobility disabilities have almost no accessibility to public infrastructure in Ukraine.

[2] For example, this cover story in New Times magazine (September 23, 2016), which details the life stories of eight Ukrainian Paralympians: http://m.nv.ua/publications/vystuplenie-ukrainskih-paralimpijtsev-v-rio-stalo-mirovoj-sensatsiej-nv-35-226151.html