On April 24, 2019, the Jordan Center hosted Daria Ezerova for her talk “Post-Soviet, Post-Industrial, Post-Future: Rethinking Space After the End of Communism”, which focused on the “afterlife” in architecture, literature, and cinema of the Soviet vision of utopian progress. Dr. Ezerova specializes in twentieth-century and contemporary Russian culture and society, with a specific focus on spatial theory, ideology, and Putin-era literature and cinema. Her current book project--“Derelict Futures: The Spaces of Socialism in Contemporary Russian Literature and Film”--examines how political power shaped the representation of space and time after the collapse of the Soviet Union. She is currently Visiting Assistant Professor of Russian Studies at Davidson College. The talk, as part of the occasional series, was introduced by Anne Lounsbery, Associate Professor and Chair of NYU’s Russian and Slavic Studies Department.

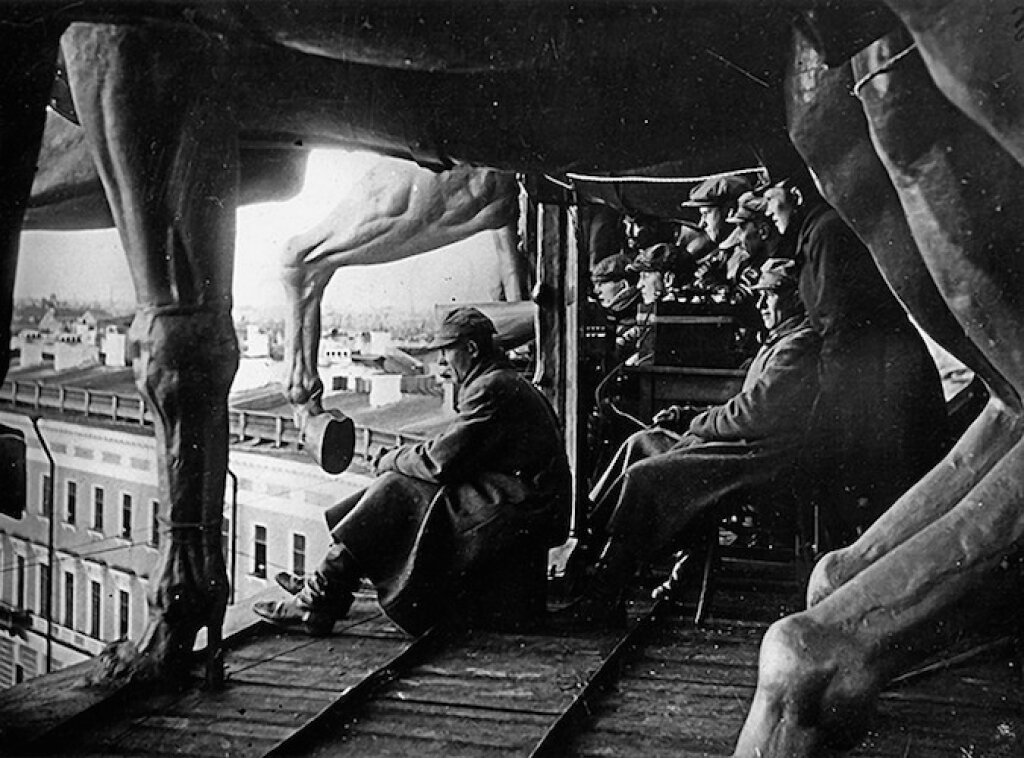

Professor Ezerova began her talk by showing a photo taken from the inside of the Hammer and Sickle Metallurgical plant. Once a symbol of Soviet Union’s mastery of modernity, the plant has been abandoned, and and now stands like a ruin of an ancient civilization. According to Professor Ezerova, “the ruins of Soviet futurity are derelict, since the Soviet Union does not exist – the forces that created it have disappeared. However, as shown by the empty carcass of the Hammer and Sickle building, the shell of this future is still standing”: thus the Soviet past still haunts contemporary Russian culture.

Ezerova explained that Socialist realism, the official art of the Soviet Union, developed special codes for representing space in literature and film, ordering spaces in accordance to the following hierarchy: the village, the factory, and Moscow. These spaces structure the archetypical socialist realist narrative: as the character journeys from one space to the other in this hierarchical triad, they attain greater consciousness at each stage. Ezerova identifies the factory as an intermediate space between the village and Moscow. By progressing through the factory, the hero of socialist realism attains a heightened consciousness, becoming the new man who leads the citizens into a utopian future.

After the Soviet Union collapsed, many of its economic ties with the former republics were severed, causing industrial sites to fall into disrepair. Images of decay across the territory of the former USSR – starkly physical symbols of the broken promises of communism – are one result of this economic collapse. While in the center of Moscow former factories such as Vinzavod, Artplay, and Red October have been turned into hip gallery spaces, helping to transform run-down neighborhoods into cosmopolitan hotspots, throughout the rest of Russia many factories remain derelict spaces--as is dramatically evident in the Hammer and Sickle metallurgical plant.

Ezerova also discussed Victor Pelevin’s novel Generation P and Aleksei Balabanov’s film Cargo 200, both in relation to the concept of “heterotopia”. Heterotopias, according to Michel Foucault, “are something like counter sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites, that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted.” Such places are “outside of all places, even though it may be possible to indicate their location in reality.” In the post-Soviet context, Ezerova noted, heterotopias are particularly illuminating since they are linked with distortions in the traditional perception of time. Thus in Generation P, the heterotopia marks a break with the historical time of the USSR. Despite the novel’s characteristically postmodern elements of caricature, it also suggests progressive time and forward movement as it explores what happens in the 2000s as Russia’s economy recovers and the country enters a time of economic stability.

Professor Ezerova then discussed Aleksei Balabanov’s Cargo 200, a polarizing film that has provoked much discussion and debate. Described as a “colossal psychological ordeal,” the film challenges the spectator on every level. Professor Ezerova pointed out the shooting sites used in the film, such as the Cherepovets Steel Factory, emphasizing that the journeys across the industrial park hint at the upcoming terrible events and gruesome scenes. The film’s naturalistic horror is focused on debunking the Soviet idea of utopia. It is suffused with Soviet symbols that establish its critical intention from the outset: it pairs emblems of communism, such as red banners and busts of Lenin, with a soundtrack comprised of mid-1980s pop music, creating an “overwhelming audio-visual cacophony loaded with harsh commentary.”

Ezerova emphasized Balabanov’s meticulous reproduction of the Soviet style of visually representing factory space, explaining that “the constructivist aesthetics of towering smokestacks and interlacing pipelines are shot from low angle with long takes that emphasize their vertical lines.” The factory is portrayed as functional in its full capacity, disconnected from the consciousness of the protagonists, and indifferently absorbing the violence around it. The central role of the factory creates a space of entrapment; a space of trauma. According to Professor Ezerova, the industrial park oppresses, reducing the film’s space to a squalid room to where the kidnapped girl is trapped.

Ezerova explored such challenging images in order examine how Russian writers and filmmakers have responded to dramatic political and social changes since the fall of the Soviet Union “by appropriating and transforming the elaborate and highly ideological codes developed under the auspices of the official art of the former regime.” Socialist realist representation of space, once tasked with foretelling the future, is now used to to comment on the present and on the kinds of progress present-day Russian is able to imagine. Professor Ezerova ended her talk by quoting Svetlana Alekseevich: “In the nineties… yes, we were ecstatic; there is no way back to that naiveté. We thought that the choice had been made and that communism had been defeated forever, but it was only the beginning.”