On November 9, 2020, the Jordan Center hosted Katja Bruisch, Professor in Environmental History at Trinity College Dublin, for a talk on the peatlands in late imperial Russia. By tracing the messy and arbitrary process by which peatlands were appropriated as resources, the talk reflected the relationship between state, economy, and nature. A historian of modern Russia, Professor Bruisch is interested in the interplay between social, political and environmental change, particularly in the Russian countryside. She has worked on the role of experts in dealing with the ‘agrarian question’ in the late imperial and early Soviet periods. In her current project, she explores ways to integrate environmental perspectives into the history of the modern Russian economy, tracing the transformation of peatlands into hinterlands of industrializing cities and the social and environmental legacies of peat extraction and wetland drainage since the imperial period. Bruisch’s talk was hosted by Anne O’Donnell, Assistant Professor of Russian & Slavic Studies at New York University. If you missed this talk, you can stream it here.

Professor Bruisch started by recounting her experience in Moscow during the historic drought and peat fires of 2010. A 2010 New York Times article published at the heat of the crisis revisited the Soviet engineering project that drained these peatlands to generate electricity, using the Revolution as a handy shortcut to explain what had gone wrong in Russia. Bruisch, however, was not interested in using her expertise on the vulnerability of drained wetlands to point fingers at the past errors. Rather, she tried to find out why people in the past would think that appropriating Russian swamps was actually a good idea.

“Like any other parties of nature, peatlands are not naturally a ‘resource’,” she stressed, citing geographer Gavin Bridge’s consideration of “resources” as a cultural category into which societies place the “useful” or “valuable” components of the non-human world.

This brief intro, which deconstructed the normative definition of natural resources as extractivist and anthropocentric, allowed Bruisch to segue into the heart of her subject: the messy and arbitrary social process through which peatlands were explored, mapped, priced, and exploited. Peat extraction in Russia actually predated the Revolution-- it can be traced all the way back to the 18th century.

“Peat appeared as a potential industrial fuel in scientific writings; however, it was only in the second half of the 19th century that manufacturing enterprises began to use it more systematically,” said Bruisch. On the one hand, it represented a national achievement. A pavilion at the 1882 All-Russia Art and Industry in its exhibition in Moscow displayed samples of peat from the provinces amidst desirable luxuries consumer goods and cutting edge technologies. On the other hand, the peat samples stored energy similarly to the better known coal. “The extensive marshlands of Russia constituted reservoirs of untapped resources for industrial growth,” added Bruisch. At Moscow’s border with the Vladimir province, Russia’s largest textile company, Nikolskaya Fabrika, exploited around 1,315 state-owned peatlands, where more than 5,000 men and women had dug out some 8 million pood (288 million pounds) of peat to power the mills.

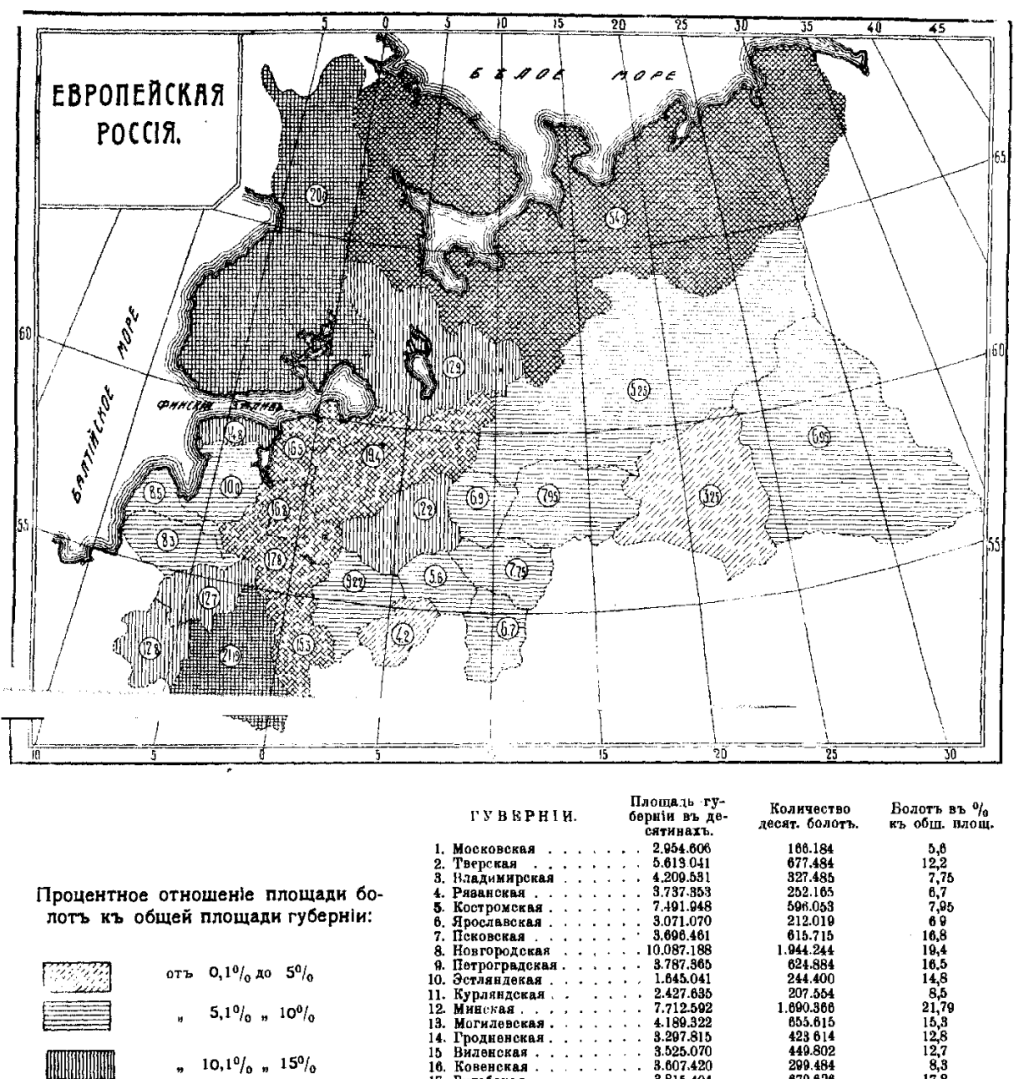

Bruisch then spoke of the role of peat in the rise of Russia’s fossil economy, the role of the imperial state as a resource maker, and the social practice of mapping and pricing swamps. She noted a spike of growth (407%) in peat fuel use from 1887 to 1913, attributing it to the expansion of industrial production in the empire’s central industrial region. With the advent of the textile industry as a catalyst of social and environmental change (e.g., rise of capitalist labor relations even before the end of serfdom In Russia), textile mills required plenty of heat energy originated from the peat plots close to the mills.

Citing environmental historian J. R. McNeill, Bruisch argued that cheap energy and industrialization created connections between distant corners of the Russian empire (e.g. Vladimir Oblast and Central Asia), and between labor (of both men and women) and land. “Transformation of peatlands into extraction sites was predicated upon the mobility of the rural population in the decades following the end of serfdom, when seasonal peasant workers provide the bulk of labor for Russia's growing industry,” Bruisch highlighted.

The exploitation of peatlands for industrial use accompanied the 19th century anxieties about the depletion of Central Russian forests, leading the intelligentsia and state officials to construct a hierarchy of ecosystems ranked for extraction. Bruisch recounted Nicholas I’s program to foster peat extraction as part of the efforts to conserve forests and to turn unprofitable state-owned wetlands into value-bearing assets.

“However, the abundance of peat was a hypothesis rather than a proven fact,” Bruisch reminded us in the end. The Q&A session then gave rise to several fascinating questions concerning imperial identity, Siberia, political economy, as well as comparisons with the cases of northern Germany, Canada, Ireland, and Scandinavia.