Frances Bernstein is Associate Professor of History at Drew University and Research Scholar in the Department of Russian & Slavic Studies at NYU in 2014.

Congratulations, belatedly, on the International Day of Persons with Disabilities (December 3)! As we in the United States get ready to mark the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act, many of us concerned with disability issues find ourselves in a contemplative mood. Having recently returned from Moscow, where I attended the 7th International Disability Film Festival (more on this in my next post), IDPD seems an appropriate occasion on which to reflect upon the status of people with disabilities in contemporary Russia.

Over the last few years disability has been in the news quite a bit, especially as compared with the almost total embargo on the subject in the USSR (disabled WWII veterans excepted). Given the deeply entrenched obstacles—physical, social, cultural, material— to participation in public life by people with disabilities, whatever mention is made is still noteworthy.

Drawing on the buzz generated by the 2012 British Paralympics (when both the games and players became sexy), the Sochi Paralympics attracted an enormous domestic viewing audience in Russia—a cumulative 625 million— suggesting a growing tolerance (that accursed word) for people with certain physical and sensory impairments. The country has come a long way from 1980, when the Soviet Union turned down the chance to host the Paralympics (they were already hosting the other games) because “There are no invalids in the USSR!” (Just as there were no dissidents, prostitutes, or, needless to say, homosexuals. Or, 34 years later, just like Sochi mayor Anatoly Pakhomov’s pre-games declaration that there were no gay people in his city either).

The games were a mixed bag with respect to disability, despite the organizers’ pledge to make Sochi barrier-free. On the one hand, Putin attended the Paralympics Opening Ceremony the same day a "Unity with Crimea" march was being held in Moscow. On the other, the ceremony lacked both sign language interpretation and closed captioning. All those amusing construction gaffes we found so entertaining in the run-up to the games would become much less funny when encountered by athletes with disabilities, who were met with steep ramps, broken lifts, narrow and heavy doors, inaccessible toilets and showers, and a scarcity of braille signage, among many other problems.

High-level international censure came in response to Russia’s actions in Ukraine; the anti-gay law (in effect since June 2013) also prompted wide criticism. Unsurprisingly, disability activists and Paralympics sponsors and attendees were noticeably quieter, although politics entered the arena there as well. Thus only one member of the Ukrainian delegation, biathlete Mykhailo Tkachenko, participated in the Opening Ceremony parade to protest Russia’s incursion into Crimea. In its own symbolic response to foreign criticism, the Russian Paralympic team entered the stadium to the 1988 song “The Last Letter” by Nautilus Pompilius, better known in Russia as “Goodbye, America.” To my knowledge, only one high-ranking politician— Bent Hoeie, Norway’s Health Minister and its official representative at the games— made the explicit point of linking gay rights with the Paralympics by attending with his husband.

It was a different piece of federal legislation, the Dima Yakovlev law (in effect since January 2013), that is most explicitly associated with the Paralympics. Named for the Russian toddler who died after his American adoptive father left him in a car for nine hours, the act banned the adoption of Russian children by Americans. As limited as the practice has been in Russia, the domestic adoption of children with disabilities is virtually nonexistent. Moreover, parents of babies born with disabilities are pressured into relinquishing custody to “invalid” children’s homes and orphanages rather than trying to raise the children themselves. Many who were in the pipeline for adoption by Americans have considerable special needs and no options beyond institutionalization. The fate awaiting the vast majority of these children is bleak, and at least a few with serious health problems whose adoptions were blocked have died.Children with disabilities unable to function independently are typically transferred at 18 to institutions for the elderly, where they remain for the rest of their lives.

Several Paralympians, notably US athletes Tatiana McFadden and Oksana Masters, both adopted from orphanages in the FSU (McFadden in 1994 from Russia and Oksana Masters in 1997 from Ukraine), spoke out against the ban before it was signed into law. Equally unsuccessful was the call for an international boycott of the Olympics by Boris Altshuler, the physicist and children’s rights advocate, to pressure Putin to overturn the law.

Whatever level of acceptance was gained from the games for people with disabilities, the discomfort in Russia with developmental and mental disorders remains palpable. Disability became overtly politicized again in the summer, with the “discovery,” published in many pro-Russia newspapers and websites, that Andriy Parubiy, Maidan “commander “and Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine [from which he would resign in early August], had been diagnosed as a child of six with a mild form of mental retardation (легкая форма умственной отсталости). The hard evidence for this claim was a medical certificate from the Central City Hospital of Chervonograd, where Parubiy was born and raised. For readers commenting on the story, such proof was unnecessary: “What do you need a doctor for? You can tell by his mug that he’s a retard.” (При чем тут справка ?! У него на морде лица "написано" что он дебил.).Nonetheless, the diagnosis was corroborated by a former neighbor, who pointed to the fact that as a child Parubiy crushed and ate bugs, and a school athletics teacher, who asserted that Parubiy’s condition was evident in his predilection for boys, culminating in his attempted rape at 14 of a classmate in the locker room.

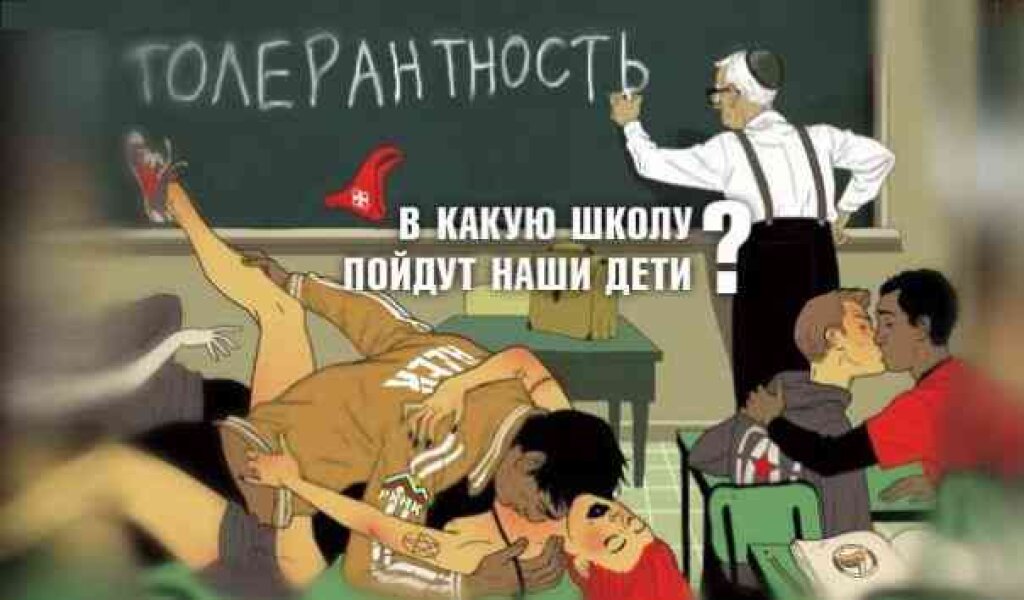

Branding one’s opponents as “f*ggots” or “yids” is not uncommon in Russian political rhetoric. But as familiar as this practice is, the “retard” (дебил) label, whether on its own or combined with these other, more familiar insults, seems fairly novel. Thus Ukraine became “Ukrainian porno-political loony bin” (Украйнский порно-политический дурдом), and “Jews, idiots, and homosexuals are governing the proud and independent Ukies!” (Евреи, идиоты и гомосексуалисты правят гордыми и независимыми хохлами!!)

Lest anyone believe that only one side of the political divide has employed this odious practice, let’s not forget the very catchy song and video “Our Loony bin is Voting for Putin” (Наш дурдом голосует за Путина) from the run-up to the last presidential election, with its own conflation of mental illness and “deviant” sexuality. Missing from the troika was the final plank in the arrangement, anti-Semitism, although the inclusion of both Blackshirts and the Nazi salute seem close enough.