Every day that I don’t write about the Malaysian airplane brought down in Ukraine is a day I feel like I’m somehow derelict in my duty. And yet I don’t know where to begin. Even worse, I don’t know where it will end.

The easiest part, of course, is to lament the senseless loss of life, of the passengers specifically and the victims of the Ukraine conflict more generally. Where to go from there is more problematic. Literary critics are not political scientists—we are the poster children for Irrational Choice Theory. But if there’s one thing we’re trained to do, it’s analyze the way stories work. And the story we’re getting now demands critique.

Newswatchers should not be surprised to learn that the Russian and American media are telling completely different stories about the airplane disaster. After all, why should this particular incident be any different? But it is the Russian media narrative that interests me today. And even if it should turn out that the Russian separatists had nothing to do with bringing down flight MH 17 (and, frankly, I’m not holding my breath for that one), the narrative itself is hugely problematic.

In the old days (back when the new century was still numbered in the single digits), Putinism was a simple, low-context narrative: high oil prices and managed democracy were about the aggrandizement of the state and the economic improvement of significant swaths of the population. This was a low-impact ideology that however odious it might have been to some, was relatively easy to live with.

But after 2012, Putin found he had a new story to tell, or had to tell a new story. Suddenly faced with civic movements that actually challenged the state’s corrupt political machine, Putin and his government had to stand for something more. The end-of-the-year amnesties and the Sochi Olympics now look like early Putinism’s last gasp: greatness, spectacle, and grand gestures rather than policy.

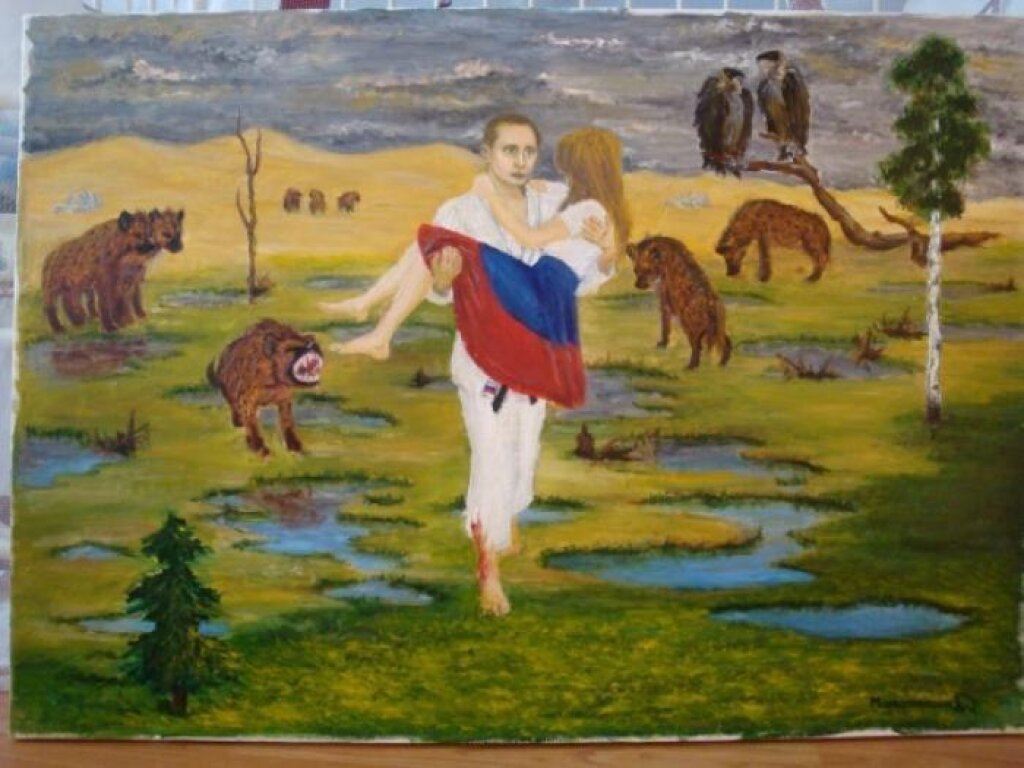

Putin now claims to be the global standard-bearer for traditional values, but that is only part of the story. The RF’s ongoing intervention in Ukrainian sovereignty has crystallized the most truly powerful narrative: that of the Aggressive Victim.

Those who want to assert historical patterns (a dangerous business, since it always simply justifies whatever’s happening at the moment) can point to the longstanding traditions of Slavic martyrdom—what Slavic country hasn’t claimed to be the Christ of Nations? Russia “saved” Europe from the Mongols, Poland “saved” Europe from Russia, Serbia “saved” Europe from the Turks…In this light, Europe has proven to be a particularly ungrateful damsel in distress.

But Slavs can’t claim a monopoly on this sort of victim narrative (even if a monopolistic approach to victimhood is precisely the problem). Certainly, the US after 9/11 indulged in similar national histrionics, “saving” Iraq to the brink of failed statehood.

The narrative of the Aggressive Victim is the perfect distillation of 1990s post-imperial melancholia and post-Yeltsin jingoism: once brought to its knees, Russia is rising up against all the forces that would push it back down. Including the very forces that feel threatened by it.

Here the crusade against LGBT rights fits perfectly with Russia’s expansionism into the territory of a neighbor it never quite believed was sovereign: no competing claims of victimhood can be tolerated. To the contrary, the enemy (whether internal, like predatory gays “recruiting” innocent children and liberal “fifth columnists” who dare complain about the new order, or external, like exhausted Ukraininans who dare to throw out the latest in a long line of elected kleptocrats and reject stronger ties with the RF) must always be transformed into a terrifying, and strangely familiar bogeyman (again like the Ukrainians, who, in a move straight out of the Milosevic playbook, have mysteriously waited six decades to reveal their true nature as Hitler-loving fascists). The sins of the Banderovtsy are visited unto the seventh generation.

The recent revival of a Stalinist opera as a patriotic crowd pleaser about the “liberation” of Crimea shares a logic with Channel One’s report of an obvious urban legend as fact (the crucifixion of a three-year-old ethnic Russian boy by Ukrainian “fascists”). Even the downing of Flight MH-17 is part of a plot to discredit Russia: witness the assertion of one of the separatist leaders that the airplane was full of defrosted corpses rather than living, breathing human beings. Any evidence offered against the official narrative is simply a “provocation,” and any allegation of Russia’s wrongdoing is part of a plot against the motherland.

A healthy government can be relied on to reject conspiracy theories. An unhealthy government helps disseminate them. This is not to suggest that conspiratorial narrative is top-down—far from it, the paranoid rhetoric of today’s Russian media can be traced to the popular fiction of the past two decades. One of the leaders of the Eastern Ukrainian separatists is an author of an entire series of science-fiction novels about Russia’s impending war first with Ukraine, then with NATO. In the past, it was easy to dismiss this sort of thing as inconsequential (and I have spent years wrestling with my own doubts as to how much significance to attribute to them in my research). But now we are watching national fantasy being written before our very eyes, and it’s a national fantasy that wants desperately to be a new national epic.

The competing truth claims about all the recent events in Ukraine, but about the Malaysian jetliner in particular, show one of the great epistemological dangers in the postmodern condition: no document, no footage, and no testimony can retain the status of unequivocal evidence. But the national epic fantasy at issue here is about more than simple propaganda. It is about reinforcing a narrative of victimization designed to appeal to an unhappy citizenry (and what Russian citizen lacks the justification to feel aggrieved?)

Accusations of propaganda and truth distortion are hurled in all directions, and each side accuses the other of being “zombified” by television. It is a situation that obliges all of us to consider our own subject positions relative to the flows of information washing over us every moment of the day.

And so I ask myself, on a regular basis, whether or not I’m just brainwashed by an American media bent on demonizing Putin. But, to be blunt, I don’t need the American media to make me loathe Putin—that’s what the Russian media are for. My antipathy is not that of the lumpenAmerican ready to see any hostile foreign leader as the latest Saddam Hussein; my antipathy is based on a sense of deep connection with Russia, a sense that what goes on there implicates me more than in any other country beyond America’s borders. I loathe Putin the way I loathed George W. Bush. I didn’t vote for either of them, and they each seemed hell-bent on rendering a country I love unrecognizable.