Watch the event video here

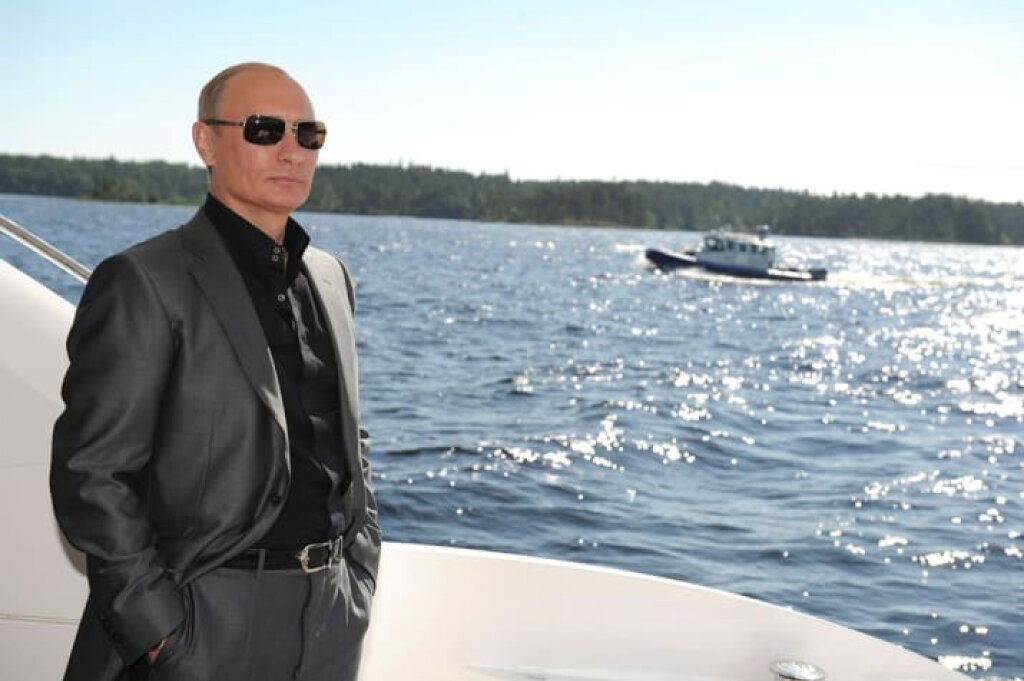

Surprising no one, Vladimir Putin secured his fourth and possibly final presidential term in an election last March, which means Russia will have a Putin-led government until at least 2024. If Putin chooses to retire then per constitutionally mandated term limits, he will have ruled Russia for a quarter of a century (counting four years as Prime Minister), as long as some of the more notable tsars.

Putin typically makes key policy decisions in consultation with a tight inner circle of confidants, which can make predicting the Kremlin’s next move a tricky business. A panel of scholars gathered at the Jordan Center on April 12 to discuss what they think the next six years of Putin will mean for Russia and global politics.

For Henry Hale, a professor of political science and international affairs at George Washington University, Putin’s fourth term raises the question of succession, which can throw authoritarian governments into crisis. As long as Putin’s grip on power appears secure, Russia’s various elite factions will line up behind him. But if Putin turns himself into a lame duck by announcing his imminent retirement, particularly without naming a competent successor, it could set off a struggle among those factions to put their man in the top spot.

Hale cited as an example Boris Yeltsin’s second term as president. By 1999, Yeltsin’s weakening position prompted a group of regional oligarchs to “revolt,” and only a combination of the Moscow apartment bombings and the reinvasion of Chechnya secured the presidency for Yeltsin’s chosen successor: Vladimir Putin.

Putin faces two main challenges in his fourth term, Hale said. The first is sustaining the popularity of his regime—staving off feelings of staleness or fatigue with Putinism in the population at large. Hale suggested that some of Putin’s recent strategies might be nearing their limit. Stoking anti-westernism and conservative values has successfully shored up public support since at least 2012, but the former might run into a baseline Russian preference for stability and the latter empowers forces on the radical right that jeopardize other priorities, like the Eurasian Economic Union. The “rally-around-the-flag” effect of inflated support for Putin that followed Russia’s annexation of Crimea and intervention in Syria has endured for years, but can Putin simply spark another international crisis when his popularity begins to slip? One counterintuitive option for Putin might be to seek rapprochement with the West, said Hale.

“There’s potential support for him to tap into,” said Hale, noting that in surveys a plurality or majority of Russians consistently say they want “partnerly” relations with the West. “He’s supported for being a foreign policy moderate, not for being a foreign policy hawk.”

Putin’s second major challenge is to devise an exit strategy such that he can eventually retire, enjoy his wealth and status, and not fear repercussions from an unreliable successor. His options here range from following Xi Jinping’s example and abolishing term limits altogether to fragmenting power among several competing groups, as Bidzina Ivanishvili did in Georgia.

Yoshiko M. Herrera, a professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said that Putin’s heretofore secure position has relied on consistent economic growth (though interrupted in 2008 and 2014), media control, nationalist messaging, and the use of violence. In this last category Herrera included prosecuting oligarchs such as Michael Khodarkovsky, conducting targeted assassinations, threatening civil society leaders, and launching military actions abroad.

Herrera also emphasized the importance of the regime’s institutional manipulation, such as barring opposition leader Alexei Navalny from running in last March’s election. While Putin’s popularity is real, Russians may feel that he is the best of bad options. If so, he could be vulnerable to a competent, charismatic challenger, forcing the regime into a “relentless hunt for potential rivals,” Herrera said.

Graeme Robertson, a political scientist at the University of North Carolina, challenged the idea that the election was a rote, essentially meaningless exercise. Putting on an election is a challenge for authoritarian regimes. Officials need to ensure both high levels of turnout (difficult when the outcome is preordained) and a landslide victory for the incumbent (without resorting to fraud so blatant that it prompts protests). Putin’s government succeeded on both marks, achieving close to their “70/70” goal of 70 percent turnout and 70 percent voting for Putin. Moreover, March’s election saw weak showings for the “young communist” Sergei Udaltsov and “pro-Western liberal” Ksenia Sobchak. The failure of Sobchak’s campaign in particular made Navalny look good, Robertson said.

Putin has successfully reoriented Russian politics away from materialist, economic issues and toward an emotional identification with “normal,” patriotic, conservative values, said Robertson. Putin himself has become the focus of the public’s emotional attachment, and this personalization of power will make passing rule to a successor difficult. This, in turn, safeguards Putin’s position and minimizes his risk of becoming a lame duck.

Robertson predicted continuity rather than change in Putin’s fourth term, saying that the president signalled as much in a recent address to the nation. In it, Putin again warned that Russia is surrounded by enemies and acknowledged that life for many Russians is hard, and so called for more military and social spending. Robertson said that he would be surprised if Putin backed away from anti-Western rhetoric or support for the slow-boil war in eastern Ukraine. At the same time, Putin does not need to instigate another foreign military adventure to continue benefiting from a politics of patriotism and loyalty.

Kimberly Marten, a professor of political science at Barnard College and Columbia University, also did not expect major changes in foreign policy during Putin’s fourth term, though she said that Putin’s foreign policy is less coherent and successful than is sometimes claimed. For example, Russia’s support for Syria now obliges Putin to defend Assad’s use of chemical weapons, costing Putin support internationally.

Western sanctions on Russia may have worked to Putin’s advantage, Marten said. Though Russia’s sluggish economic growth owes primarily to low oil prices and continued reliance on commodities, Putin has passed the blame to western sanctions. However, the most recent round of sanctions, imposed April 6, might be different. Among those sanctioned is the oligarch Viktor Vekselberg, who donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to Donald Trump’s inauguration and has faced recent pressure from the Russian government. Sanctioning Vekselberg makes the penalty seem almost random, which could have a chilling effect on investment in Russia, Marten said.

Audience questions touched on Alexei Navalny’s prospects as an opposition leader, the efficacy of sanctions, and whether Russian support for right-wing movements in Europe and the US is meant to “bring everyone else down” to their level.

In response to this last question, Graeme Robertson said that the success of right-wing candidates in the west cannot be blamed on Russia.

“Our problems are our problems. This desire that we have to find somebody to blame for the mess that we’ve made is understandable, but it’s misguided,” Robertson said. “It doesn’t hurt them, but I don’t think they’re playing much of an effective role in that.”