Watch the video of the event here

On October 21, 2016, the NYU Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia hosted a talk titled "In to Africa: The Soviet Union and Its Civilizing Mission as Depicted in 1920s Soviet Children's Literature" by Raquel Greene, Associate Professor of Russian at Grinnell College, who presented a part of her manuscript on the construction of race, primarily Africa and Africanness, in Russian children's literature.

Explaining the choice of the 1920s as her focus, Greene said that the decade represented the sort of freedom and creativity that ceased to exist in the 1930s. Throughout the 1920s, the focus of critique for Soviet writers was mainly Africa and colonialism, unlike later decades, when focus dramatically shifted to the United States and the state of African-American children.

One of the central arguments of Greene’s presentation was that the images that inform the visual narrative of children’s literature in the 20s can be traced in large part to 19th century Russian responses to the institution of African slavery; “many intellectuals condemned the institution, yet their perceptions of Africans as human beings were often fraught with contradictions. Writings including very sharp critiques of slavery were replete with racial stereotypes.”

For instance, one criticism from a series of historical stories for school-aged children read: "They didn't consider at all they were buying real people, tearing children away from mothers, husbands away from wives. They forgot that black people could feel, love and suffer." While Russian writers acknowledged black humanity, this was still accompanied by negative assessments: "Completely black skin, curly black hair, large thick lips [...] they live in separate tribes, obey their princes, they are pagan, frequently kill people in the name of their multiple gods." As explained by Greene, authors distinguished among Africans according to European standards of beauty and adherence to Western monotheistic tradition, as well as by stereotypes of African physicality, inherent laziness, and natural artistic inclinations.

The first Russian children's work discussed by Greene to include such differentiation was Maksimka (1875) by Konstantin Stanyukovich, whose central issues were freedom, equality and human dignity. In “Maksimka,” the crew on a Russian ship rescues a young African child whom they find floating in the water after his ship headed for America collided with another vessel. They nurse the boy back to health, and back in Russia, Maksimka is baptized into the Orthodox faith. While Stanyukovich explicitly attacks American slavery, according to Greene, concern for Maksimka's wellbeing is undercut by several negative characterizations and dehumanization: “The actions of the characters suggest a paternalism that is founded on a presumption of their own superiority.”

In the 1920s, some of the Russian children’s writers who depicted Africa and blackness confronted colonial exploitation, while others pointed at the absence of civilized development and the need for humanitarian intervention, Greene explained. But the common thread of the narratives, according to Greene, is that they underscore the weakness of western ideologies and strengthen of the Soviet Union’s moral position; “in these tales, benevolent, color-blind Soviets become alternative civilizing agents.” As Greene demonstrated with the following case studies, however, what resulted were children's texts that reinforced negative racial stereotypes and with already deep-seated negative notions of Africanness.

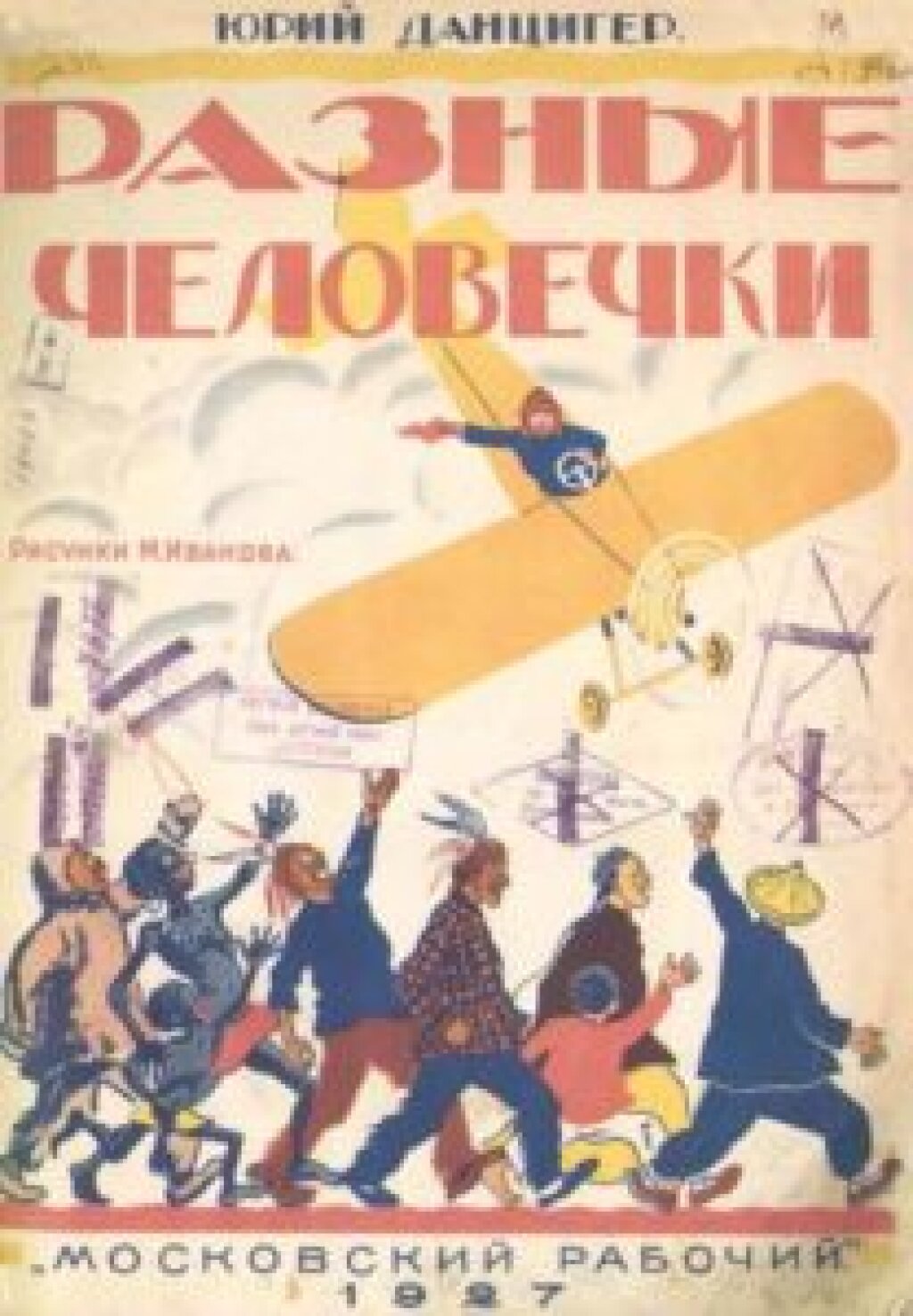

Raznoye Chelovechki is the story of a young boy, Vanya, curious to find out about different races. He embarks on a journey, first traveling to Australia where he meets aboriginals. The graphics show a stark contrast in environment between the Soviet Union and foreign lands, and it is visually difficult to distinguish aboriginal Australians from Africans. At his next stop, in Alaska, he meets “Eskimos.” At each place he visits, there is a list of complaints, confirming his assumption that life can't be as good as it is in the Soviet Union. Vanya leaves the Eskimos a radio for contact with the outside world. In Canada, he meets Native Americans, whose complaint is that in contrast to how they are often portrayed, they are not “redskins.” Vanya leaves them books. Finally, he goes to China, the only instance where he is the one receiving the gift, because “the Chinese already have everything.”

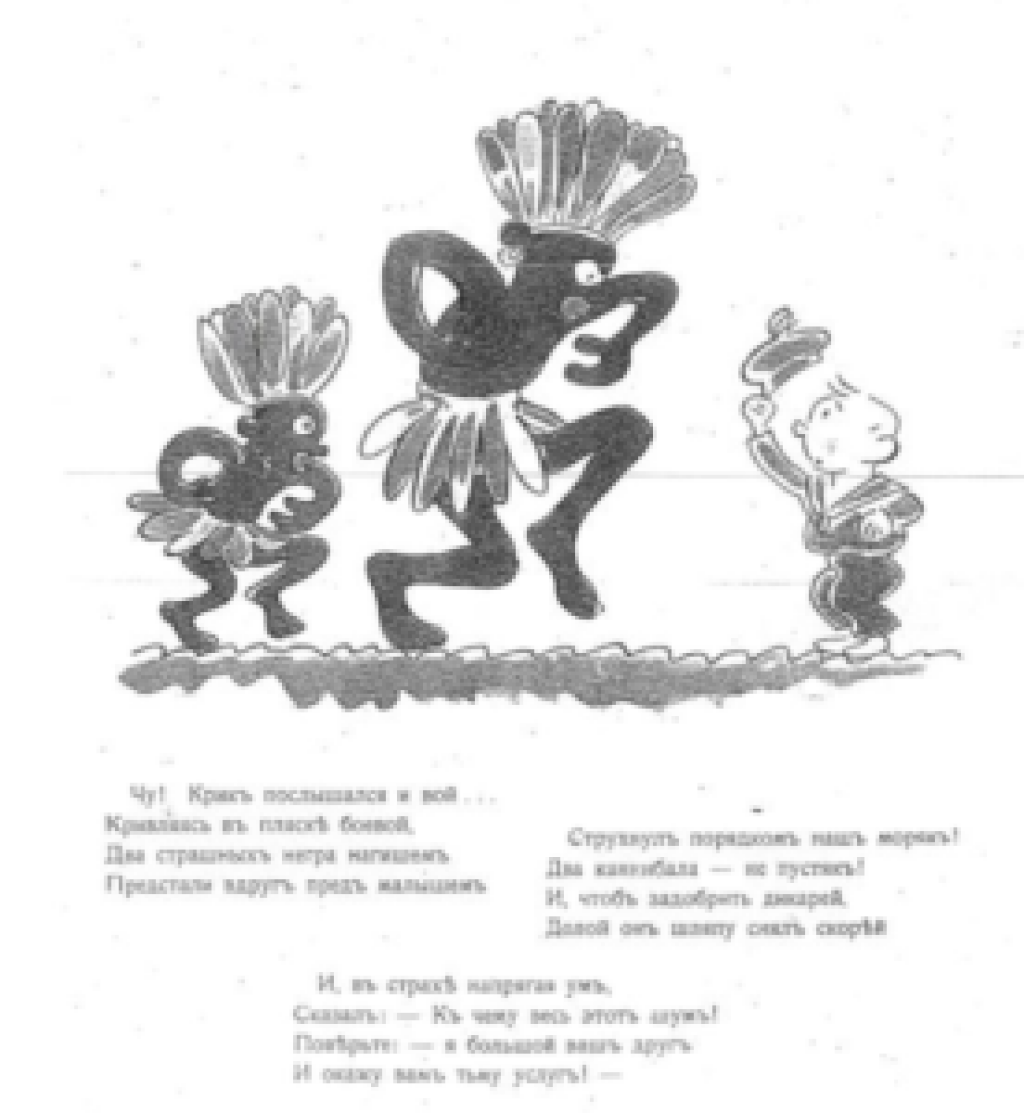

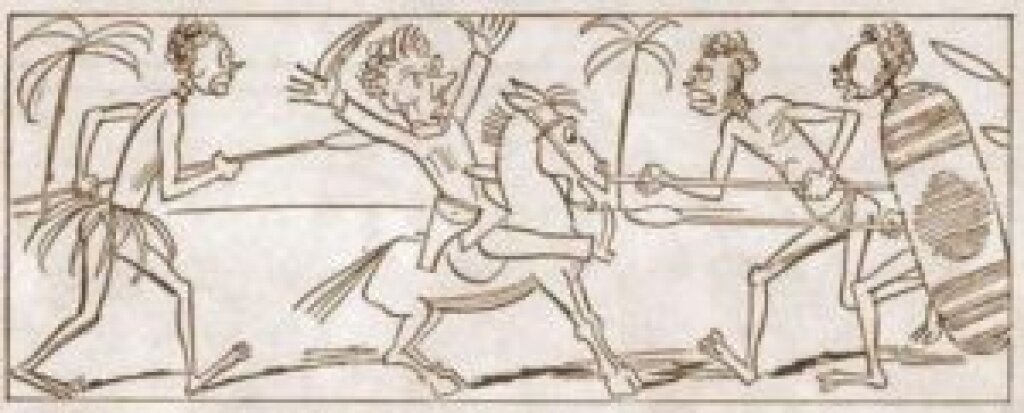

V Gyostiakh u Negrov (1920) is another narrative of a child, young Petrushka, visiting other races. His boat capsizes and he is met by native cannibals. In terms of behavior and language, the natives are essentially children, and in fact the monkey who steals Petya's clothing is smarter than the natives. In the end, they all return to Russia with Petya, who now has his own civilizing mission, but the happy ending is problematized visually; the natives are highly stylized in contrast to the white child.

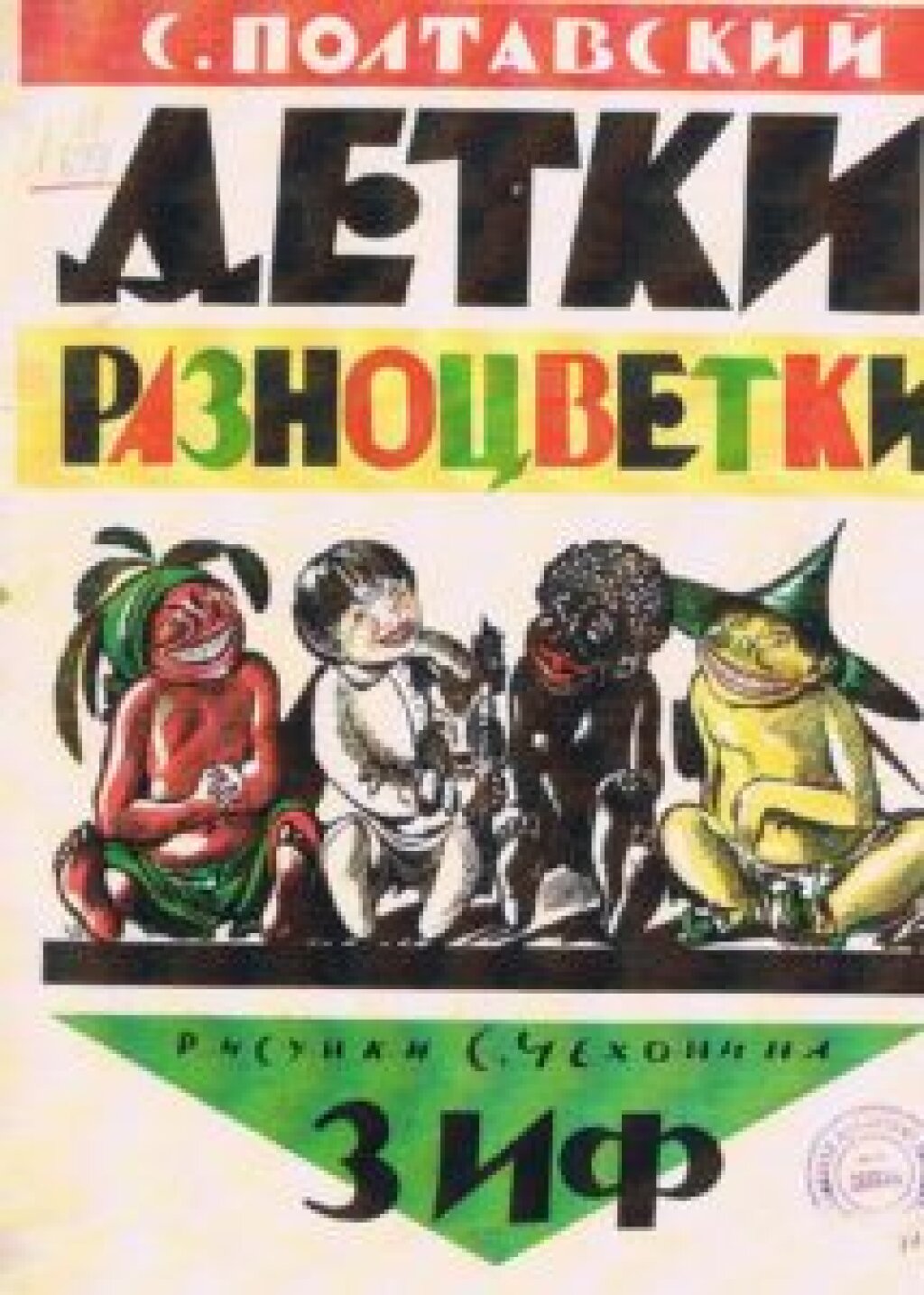

The most problematic narrative, according to Greene, is of Detki Raznotsvetki (1927), in which Africa’s otherness is depicted most significantly. Here Greene pointed to the comparison between the visual depiction of the African child with the children of "other races" that Russian boy Vanya wanted to meet. Greene interacted with the audience to interpret the illustrations accompanying these stories, noting the various forms of undress, the environment, wildlife, facial features and human extremities of children and the caricature for "ethnic dress," pointing out how the African child is the only one who is always completely naked.

Detki Raznotsvetki was criticized in the Soviet Union after its publication because its lack of a civilizing mission; there is no noble purpose, just “pure orientalism.” A number of literary circles denounced the book, as Greene explained, calling it "chukovshchino," meaning pointless entertainment. Specifically, it came under the fire of Nadezhda Krupskaya and parents of children attending the Kremlin kindergarten. As a result, its author fell into oblivion, while the illustrator moved to France, where he was met with much less hostility.

The Fantastic Adventures of Makar the Fierce, by Nikolai Oleynikov, was the first Soviet children's comic series to be published. Oleynikov was known for creating modes of expression that children could relate to. Greene said that the simplicity of the graphics and the portrayal of the natives evoked the Tintin series to her. In this work too, there is a stark contrast between how the Slavic child and the natives are depicted.

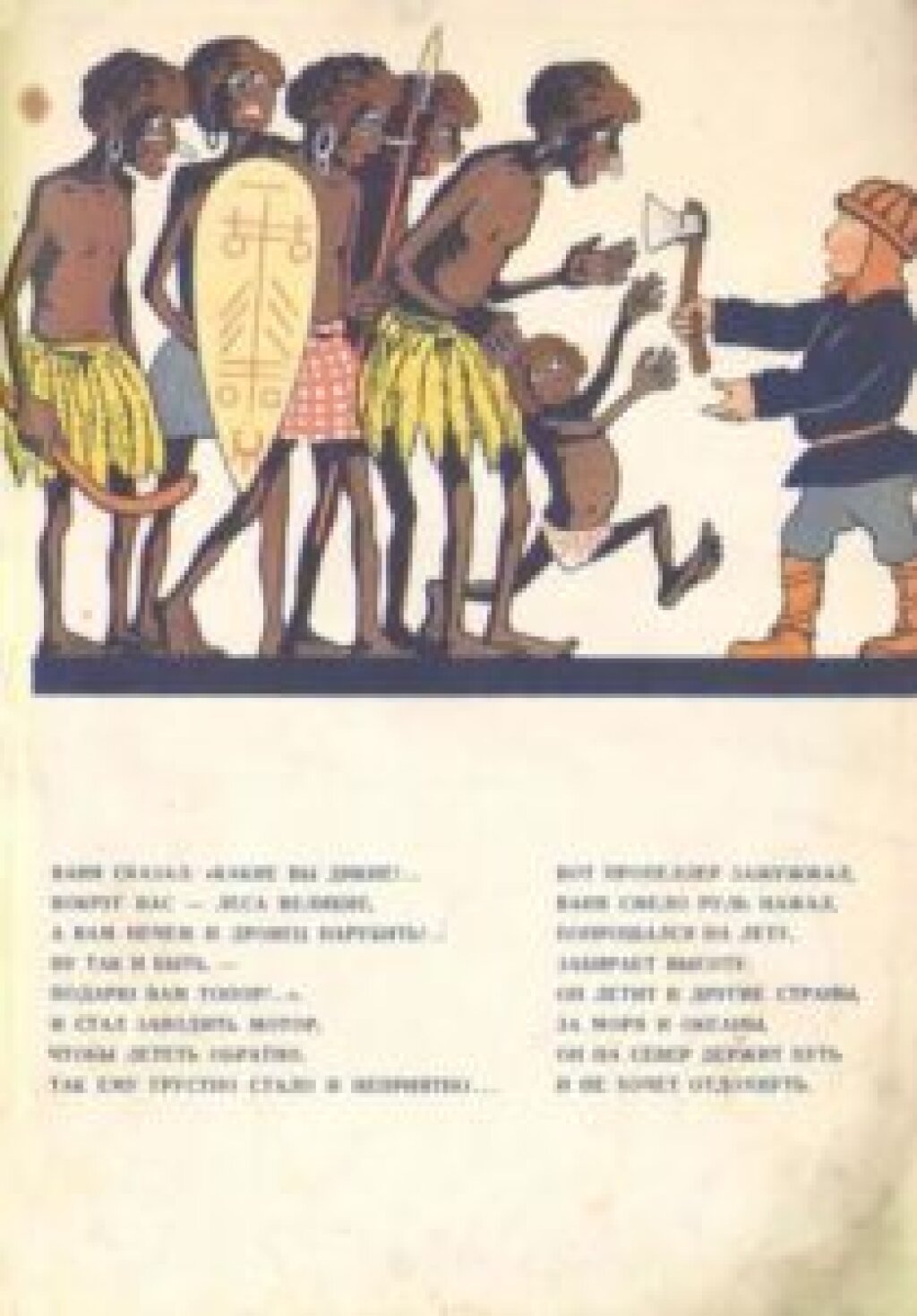

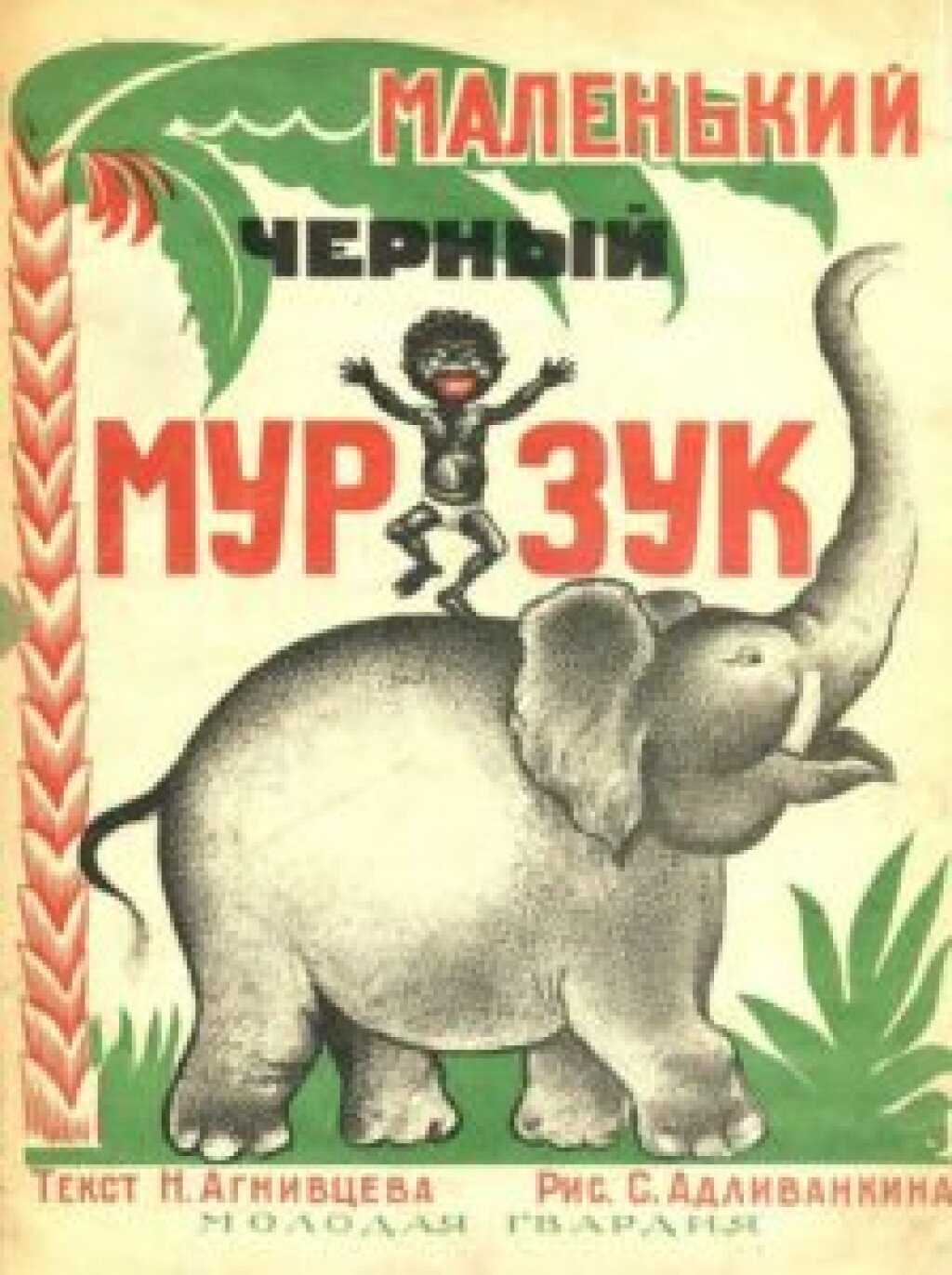

In Malinkiy Chorniy Murzuk (1926), Greene said, the African child doesn't look child-like. This is not a story of Soviet intervention but European colonialism, and the Englishmen in the story could be representative of any European power. With their false and impractical gifts and immediate exploitation, the Westerners lead the reader to think how it would be different if the Soviets were in the same position. In fact, the text explicitly asks, “is this fair?”

Many of the questions directed at Greene during the Q&A sessions had to do with other iterations of the tropes she had discussed. Greene said she has never come across stories of children discovering different races within the Soviet Union; rather, the characters were always Slavic.

In response to a question from Anne O’Donnell, Assistant Professor of History at NYU, on how she would contextualize these representations with those of Africans in non-children's literature from the same time, Greene said that since Russia had a relatively limited interaction with colonized Africa, much of the visual culture that Russian writers were informed by came from the West, in the form of travelogues, ethnographic materials, etc. “In many cases depiction of Africans were very negative and in many ways that's what these images draw from,” Greene said. In terms of how Soviet ethnic minorities are depicted, Greene explained that they were seen as further along in terms of developmental stages. While Africa was completely foreign, national minorities assumed a “mid-space, not as othered as Africans but not as advanced as their older more developed Soviet brethren either.”