Sonya Stepanova is a third year BFA candidate at NYU’s Maurice Kanbar Institute of Film and Television.

[Note: This is Part II of a two-part essay. Part I was posted this past Tuesday, 10/24.]

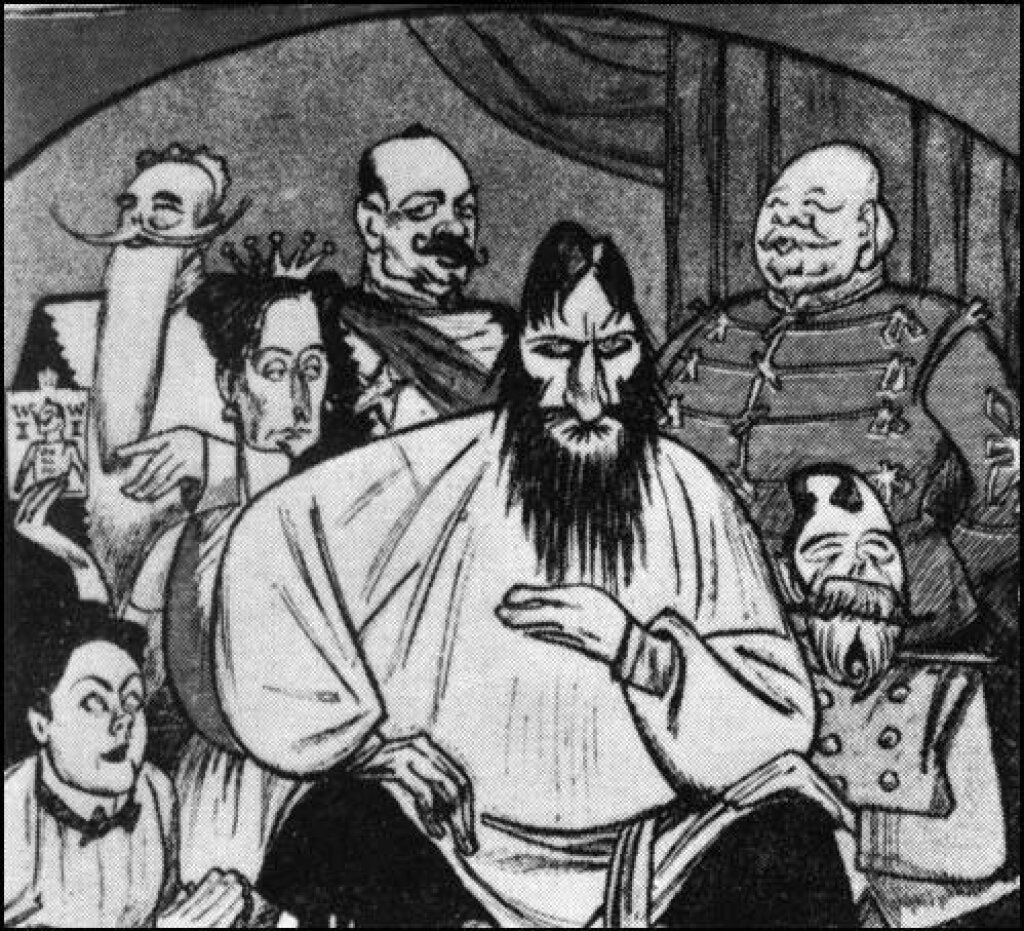

As my colleague, Nikta Mahmoodi, explained in the previous post, completing the necessary research for our documentary on Rasputin's penis proved difficult. As our ideas on the film's ideal execution changed, we found ourselves having to start from scratch on several occasions.

At no point were we entirely sure of what we were doing. After a while, all we could think about was Rasputin’s penis, which acquired a strange significance for us. We kept hoping the object would eventually leads us to some sort of epiphany, but this never came to pass — which meant the format and even nature of our project was a constantly evolving work in progress.

We began working on the film itself while the research was still in its preliminary phase. At first, we thought we would simply tell the story of Rasputin and his penis, chronicling it in a traditional, linear fashion. This initial choice immediately proved problematic — indeed, we couldn't find an entirely consistent account of the man's life, let alone his penis. Once this became clear, we abandoned the idea of making an archival documentary.

We pondered how to deal with the lack of information on our central topic. No matter how we treated our subject, we knew that for narrative reasons we would need to include a general overview of Rasputin's life. How could someone care about a person’s penis if they didn't know who the person was? Accordingly, the "general overview" portion of our film unfolds through a selection of archival materials accompanied by voiceover narration. We intentionally kept the voiceover rather ambiguous, giving as much information as possible without veering into falsehood.

Once we completed the overview and screened a rough cut to fellow members of our "Sight and Sound Documentary" course, it was time to figure out how Rasputin’s penis would fit into the film (no pun intended). After meeting with our instructor, Professor Marco Williams, we decided to pursue all possible leads and base the film on those findings, keeping its tone serious throughout. At this point, we were imagining a documentary consisting of archival footage intercut with interviews with experts. We sought out a variety of respondents, including: biologists; historians; the Russian Museum of Erotica in St. Petersburg, whose collections allegedly include the penis; and Michael Augustine, the man who found what turned out to be a sea cucumber in a locker belonging to Marie Rasputin. Who knows, we thought. Perhaps one of our experts would lead us to the penis itself!

As the final cut of the film makes clear, this idea did not pan out. Only one expert got back to us (which later turned out not to be such an insurmountable setback after all). It was at this point that we turned to Professor Yanni Kotsonis, whose insights helped us reach a turning point in our thinking. After our interview with him, we began to see the penis less as a physical object than as a symbol. We recognized that research was unlikely to lead to any concrete answers about that object's whereabouts. And that's when it dawned on us that the film's true subject had to be the journey to this realization.

One of the hardest parts of the filmmaking process was editing Professor Kotsonis’s interview. We spoke to him for over an hour, receiving much valuable information, but could only include a few minutes of it in the film's final cut.

The first cut included Nikta and me only to a very limited extent. We presented ourselves exclusively through voiceover narration, dropping in occasionally to clarify elements that were not self-explanatory on the basis of previously displayed footage. The film's chaotic tone and lack of evidence were deliberate choices meant to reflect our own state of mind. As we discovered, however, many of our classmates found this format too disorienting. To people who didn't know us at all, faceless narration would likely be even more unsatisfying and confusing.

Yet both Nikta and I were hesitant to put ourselves in the film. We'd wanted to center our project on the powerful figure of Rasputin, not two confused college students struggling with an assignment. But in the end, we decided to include ourselves. After all, the film had become a chronicle not of Rasputin's life or the fate of his penis, but of our personal experiences. It made more sense to appear in the film directly than to use potentially impersonal or contrived-seeming third-party narration. And so, one rainy afternoon, after weeks of trying to figure out how to conclude the film, we sat down and recorded our thoughts. We sifted through hours of footage, selected a subset of our own reactions, and cut these together with archival materials and the interview with Professor Kotsonis. Editing the film proved challenging, since the manner in which we presented and integrated our footage would alter the story we were trying to tell.

The final result is far from our original vision. The tone, subject matter, and even protagonist changed during the making of the film. The fact that Nikta and I were working together — for the first time, no less! — also affected the final product. I am certain that, had we tackled the project separately, each of us would have created a completely different version of the film. Ultimately, this project taught us less about Rasputin's penis than about the way humans interpret and process history and the intensely personal nature of filmmaking itself.