This is Part II of a two-part post. Part I may be found here.

Daria V. Ezerova is a Postdoctoral Research Scholar at the Harriman Institute at Columbia University. She specializes in twentieth-century and contemporary Russian culture and society, with a focus on spatial theory, ideology, and Putin-era cinema and literature.

Mikhail Vrubel

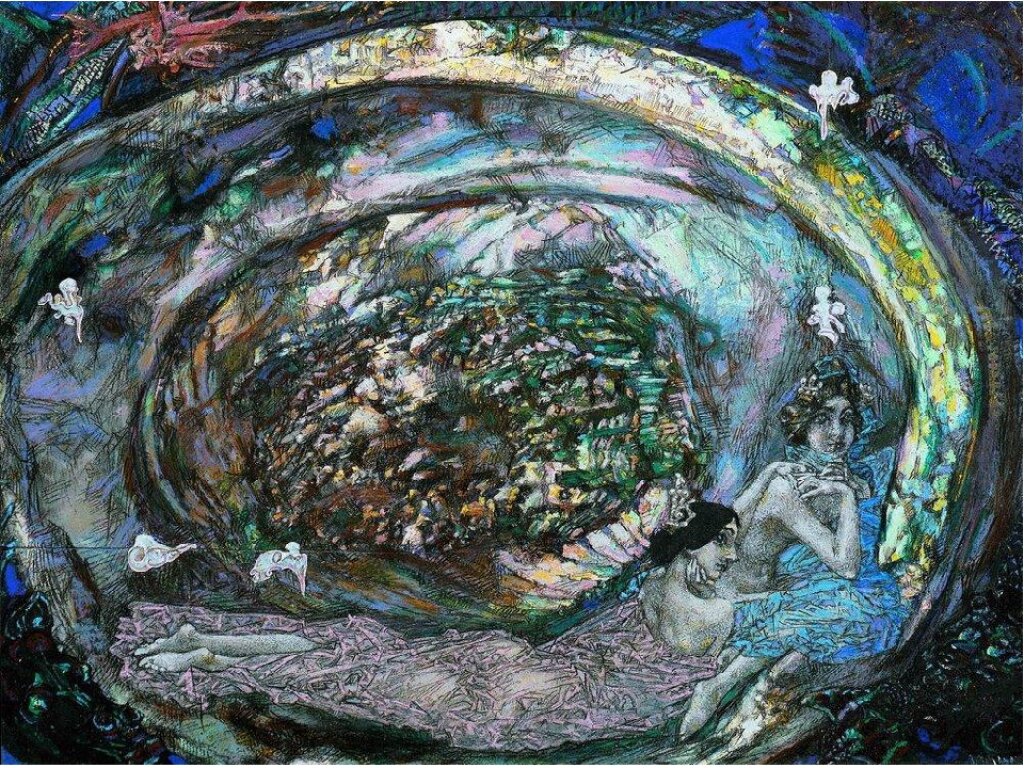

In painting, Mikhail Vrubel’s engagement with the art of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood exemplifies a lifelong negotiation of Russia’s position on the map of European modernisms. In 1883, during the celebration of Raphael’s quadricentennial at the Imperial Academy of Arts, Vrubel praised the old master’s works for their exceptionally realist quality. Shortly thereafter, Vrubel’s preferences moved further back in time as he exalted the realism of Bellini and Tintoretto. Vrubel shared his admiration for the Venetians’ lifelike works with the Pre-Raphaelites, who discerned elements of realism in the Quattrocento in order to unite Renaissance legacies with a nineteenth-century desire for verisimilitude. At the same time, Vrubel’s preoccupation with European masters indicates his concern about Russia’s place in European cultural hierarchies.

A key exponent of Russian painterly symbolism, Vrubel began his career at a time when realism reigned supreme in Russia. Through his views on Bellini, Tintoretto, and Raphael, he intended to establish continuity between Renaissance legacies and Russian realism – a continuity that would allow Vrubel to place Russian art into a broader European cultural narrative. This suggests that Vrubel saw Russia as a European cultural periphery. However, Vrubel’s engagement with a different legacy, the Russo-Byzantine tradition, complicates this viewpoint and invites a consideration of his work in the context of revivalism – a trend championed by the Pre-Raphaelites.

A common method of revivalism across national traditions in Europe was the amalgamation of two types of cultural sources – one shared / trans-European, and one national. For the Pre-Raphaelites, these sources were, respectively, The Bible and Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (1485). Unearthing (and sometimes inventing) a national past allowed them to reconcile the local with the cosmopolitan – a feature that would later make revivalism popular among Russian artists as it would let them seamlessly inscribe Russia in the European cultural context. At the same time, the Russo-Byzantine tradition would allow them to place Russia in a different cultural and historical lineage, extracting it from Western European center-periphery binaries altogether. Vrubel’s vacillation between different artistic legacies defines his foray into revivalism, creating a continuously shifting vision of Russia’s ties to European cultures.

Madonna with Child (1885), Vrubel’s fresco from St. Cyril Church in Kiev, reveals a painstaking attempt to revive the style of Byzantine mosaics, while the vibrant reds recall the Venetians (Vrubel visited Venice in preparation for this work). At the same time, the lifelike Madonna is a product of contemporary European art, with her big dark eyes and full lips resembling Rossetti’s The Beloved (1865-66). Vrubel’s later revivalist works are even more eccentric and sui generis. With its intentionally distorted perspective and unusual color scheme, his The Bogatyr (1898) consciously departs from European revivalism, suggesting that for Vrubel, Russian revivalism had to differ in style and technique as well as subject. A year later, he went further – in Pan (1899), he situated the creature of Greek mythology against a consummate Russian landscape, putting Russia on par with the fountainhead of European civilization. Thus, Vrubel’s engagement with Pre-Raphaelite-style revivalism, in which he vacillated between a desire to fit in with European traditions and to write himself out of their narrative, demonstrates that Vrubel felt at liberty to reconstruct European cultural hierarchies in his work, changing Russia’s position in them as he saw fit.

Alexander Blok

Conversations about Russian Symbolism inevitably mention Alexander Blok and this one is no exception. The PRB enthralled Blok so much that he created his own Brotherhood, as it were, the Knighthood of the Divine Sophia. Blok’s interest in interart dialogues, particularly between literature and painting (see Blok’s essay “Slova i Kraski,” 1903) is a likely source for this fascination. The Pre-Raphaelites worked across media – Rossetti and Morris were accomplished poets – and frequently adorned their pictures with frame inscriptions. And yet, in his pursuit of a syncretic artwork, Blok went further than the Pre-Raphaelites: with his interest in mysticism, he strove to annihilate the border between art and life itself – a practice that came to be known in Symbolist circles as zhiznetvorchestvo. Blok’s marriage to Lubov Mendeleeva, whom he considered a living incarnation of the Divine Sophia, suggests the influence of Solovyov’s mysticism and the aesthetics of the PRB, which prompted contemporaries to refer to Blok’s wedding as a “pre-Raphaelite event.”

Blok’s cycle “Italian Verses” (1909) demonstrates a strong Pre-Raphaelite influence. In poems “Ravenna” and “Florence,” Blok laments the cities’ bygone glory, trampled under the iron stride of modernity, much like William Morris did in the prologue to The Earthly Paradise forty years before. If “Ravenna” and “Florence” mourn the loss of European cultural riches, “The Annunciation” (same cycle) is Block’s tribute to European art, both Renaissance and Pre-Raphaelite. He transports the Annunciation scene from Nazareth to Umbria – a nod to Renaissance artists – but the eroticism in the Angel and Mary’s encounter recalls Ecce Ancilla Domini (1849-50), Rossetti’s unsettling vision of the Annunciation. In his unorthodox rendition of the Biblical scene, Block seeks purity of form and alternative forms of spirituality as the PRB did half a century earlier. However, soon Blok would turn to different inspirations and forswear Pre-Raphaelitism – for good.

Shortly after his return from Italy, Blok began to veer away from Pre-Raphaelitism. At the dawn of the Revolution, he turned to Russian themes and reconsidered both Russia’s position on Europe’s cultural map and his own artistic persona. In 1908, he wrote “On the Field of Kulikovo” and “Russia,” followed ten years later by “The Scythians,” which proclaimed Russia’s superiority to the West and portrayed Blok himself as a “barbaric lyre,” impervious to European cultural influences. Unlike Vrubel, Blok no longer negotiated Russia’s peripheral status: he cast it as a center of its own world, different, greater, and perhaps hostile to Europe, and certainly rejecting its center/periphery binary. Blok, Solovyov, and Vrubel’s experiments with Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics cast them as true-to-form modernist authors. Unrestrained by geographical borders and national traditions, they exercised their agency to inscribe their works into the European cultural narrative – or to write themselves out of it. Thus, Russian symbolism once again demonstrated that in the age of modernism, any presumed cultural border promised not separation, but mobility.