Ekaterina Chelpanova is a doctoral student at the University of Kansas.

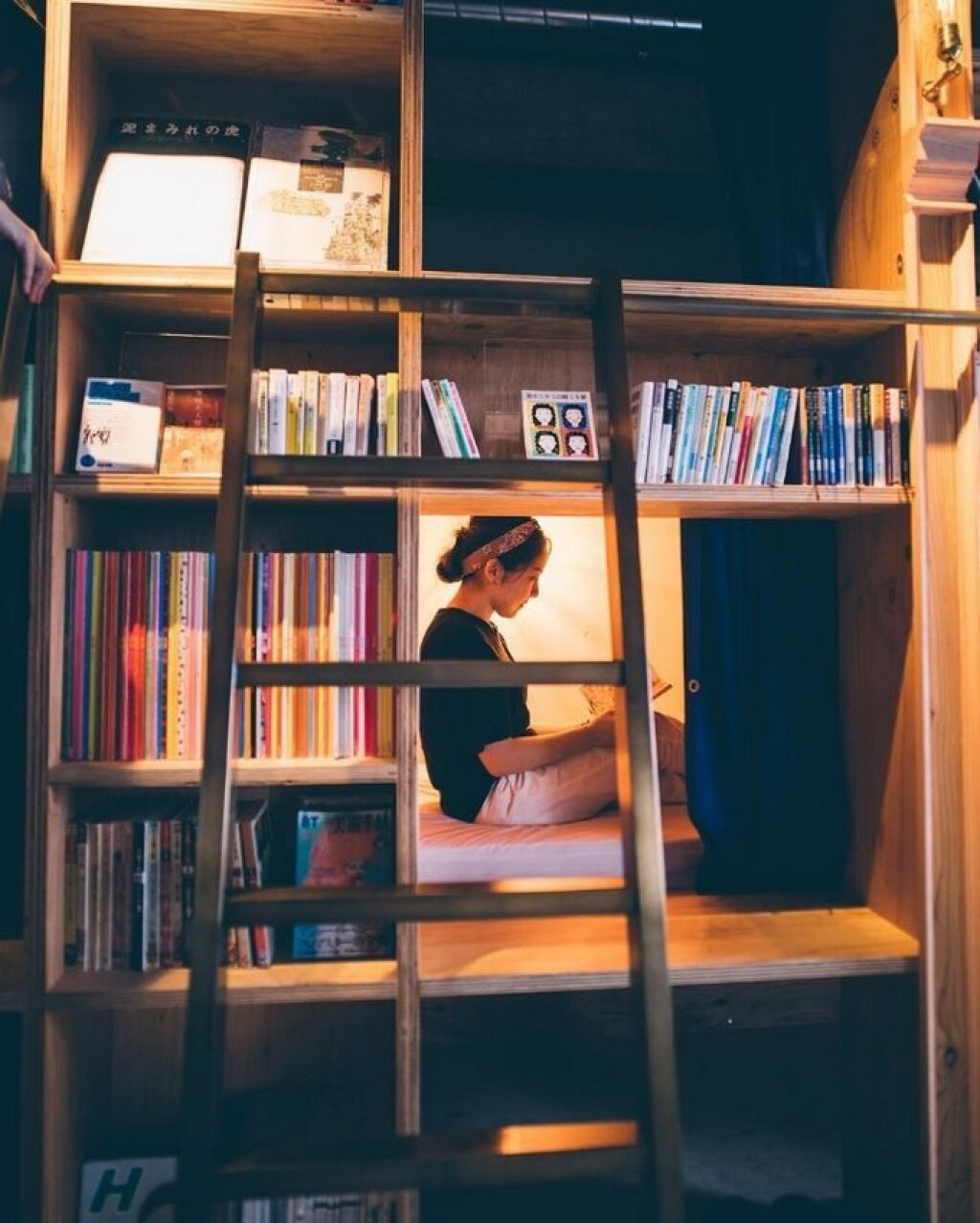

My story of immigration began about ten years ago when, while working on my thesis in a Saint Petersburg Public library one snowy evening, I suddenly came upon books by Princeton historians on my topic. I was writing about Byzantine icons at that moment. Russian academia ten years ago resisted inter-disciplinary topics, but I became interested in modern French philosophy and I sought to apply its ideas to literature and history. I became dissatisfied with the exclusive focus on historical documents and political ideas. I wanted to write about the people of the past and to understand how their psychology could be different than ours. This was the reason why American texts related to my topics of study greatly appealed to me; they seduced me with inter-disciplinary themes and an emphasis on the history of consciousness. It was the moment I started to imagine America and wonder whether one day I could find my path there.

This period of my life was not the happiest. My field, Byzantine studies, became almost extinct, my advisor, the last professor in the field in my city, fell ill and lost interest in continuing her work in the field. Some male professors “kindly” advised me to avoid an academic career (because the road to success was so “hard and challenging”) and it would be better to focus on having children instead. When confronted with my academic ambition, one of my favorite scholars, an extremely eloquent and handsome philosopher, remarked: “You are so pretty, why do you care so much about pursuing an academic career? I really think it is wonderful when girls have kids early, because kids help us all overcome egoism!” Such comments only left me feeling estranged. Uncertain about the academic job market, I turned to a business career, promising myself that I would one day return to academia I kept telling myself: “The day will come, I will have the career I have always dreamt of.” And this day did come.

From a dream in a library on a snowy evening, America materialized into reality. This reality was in many ways different from a dream, but with unexpected pains came unexpected moments of excitement.

"How Is America?"

The experience of immigration teaches you that every unexpected disappointment is compensated with unexpected moments of revelation. Soviet writer Sergei Dovlatov, who was an immigrant himself, wrote that people are neither categorically good nor bad, but rather are only transiently “good” or “bad” depending on context. This is something you learn through immigration: life and people are a neutral zone.

As an immigrant in a new and unfamiliar country, every day has brought a feeling of being unmoored, as the things I have taken for granted at home are suddenly absent, and thus at once their centrality to my identity and well-being is made clearer.

An immigrant in this situation can no longer rely on communication with, or at least the calming proximate availability of, familiar relatives and friends. I sometimes wonder if I can even anchor myself in memories of my younger years back home, as I often question whether these even belong to the same person I am now. After all, who am I now? Am I not a white sheet upon which life can write any narratives and unexpected plot twists it may capriciously choose?

I have learned to accept that I cannot know what to expect each day; and I’ve learned not to expect too much lest I suffer disappointment.

My Russian friends frequently ask me “How is America? Is it as amazing as we think of it?”

I answer: “Yes, at times... but not in a way you think.”

Often I hold back from elaborating. My experience as an immigrant is hard to articulate fully, and the only ones who understand it are those who have lived through it. In short, immigration is much like death and resurrection, which makes it a good way for Christians such as myself to test their faith.

Or maybe I am exaggerating? Maybe in immigration you just learn more about the fragility of life, and its uncertainty, whereas before the constant fragility went unnoticed due to the mediators that protect people from seeing life as it is: a circle of good friends, a city called home full of childhood memories, a particular job, and what not.

Time perception changes, and you are already not sure what was earlier and what was later. Childhood seems closer than it was before, perhaps because the feelings of childhood vulnerability have returned. Or perhaps because one sees the world, and one’s place in it, with fresh eyes, and thus leaves behind the preconceptions that people in less self-aware times assume are givens of life and reality.

Some Are More Equal Than Others

America declares that it supports equality but on every step you will be told that you are not equal. You are just not. In no way. Your deposit for an apartment is higher because you do not have a credit history here. You pay more taxes because you are a foreigner. Your educational system is not the one Americans value and trust. And, besides, they say, Russia is an unstable, unsafe country, Russian people are nationalistic, they admire their president too much, their economy is in the tank, and their literature is about depression and neurosis. What, you don't agree? How can you not agree? Really, aren't all Russians nationalistic?

Russians are just all different, like Americans are all different and, as Dovlatov said, none of us is extremely good or extremely bad, with some very few exceptions, and most of us are a neutral zone... depending on circumstances.

I have met amazing people in America, and it is amazing that they appear at the moment when you find yourself in utter despair. It is okay to despair, just never let yourself dive into it. One Soviet writer, Boris Vasil'ev, who fought in the Second World War, wrote that in war, at the moment when you are filled with “fear as heavy as mercury”, you are already dead, even if you are still alive and the enemy is far away. Never let “mercury fear” fill your soul, whatever happens. It is not worth it. Immigration deprives you of private space and a private circle, with one important exception: your soul is the last private space, and one must never become alienated from it.

So, what now? Those people who advised me not to go to America because “you are already too old, 31!” admit now that I was right having made my own choices; and they have revealed that the reason why they advised me not to try was only because they had to give up some of their own intimate dreams and hopes. Those who supported me are extremely happy for me, and I thank them every day in my prayers, because without them trusting in me, I never would have succeeded.

In my country people these days spend a lot of money on motivational trainings and programs designed to foster “personal growth.” I consider these things to be wastes of money. If you have a dream, do not give money to people who pretend that they know how to help you. Instead, surround yourself with people who will tell you as many times as you need that “yes, you are capable of achieving your dreams!” – and just start doing what you have always dreamt of doing. The best thing about America is that it is full of people who dared to do something to change circumstances for the best. America itself appeared of such an effort, and it happened far before the epoch of trainings of “personal growth”.