David Rainbow (Ph.D., History, NYU 2013) is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Columbia University’s Harriman Institute for Russian, Eurasian, and East European Studies.

Everyone’s afraid of the separatists these days; they’re messing up countries all over the place.

Britain’s Prime Minister David Cameron is sweating bullets today as Scotland votes on independence. Spain’s Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy promised to ban a referendum on independence planned for two months from now in Catalonia, where separatism, some fear, could set off a domino effect across Europe. Chinese officials have been fighting Uighur separatists for years, a struggle that’s included violence on both sides. The U.S., too, has its own (relatively tame) separatists. Seven hundred thousand people signed petitions in 2012 to secede from the Union, including one hundred and twenty five thousand Texans. The petitions prompted an official response from the federal government, a thanks-but-no-thanks direct from the White House. Separatism is afoot in the land of my birth, too: more than a million Californians are in favor of a plan that would dismember the state into six pieces. My piece would be the poorest state in the nation. Horrible idea!

What’s a political leader to do? Maybe it’s time to follow the lead of Prime Minister Cameron: ask President Putin.

If one of the Kremlin’s news agencies is to be believed (which isn’t mandatory), Cameron approached Putin earlier this year asking for help to keep Scotland from leaving the Kingdom. Russia, to be sure, has had its fair share of experience with separatists. They’re in Chechnya, Kazan, Siberia and the Far East, among other places. But Putin has been fighting separatists since before anyone knew who he was. He cut his teeth in the post-Soviet political world fighting Chechen rebels. Today Grozny isn’t setting any records for attracting foreign tourists, but it’s still part of Russia. If a series of campaign ads from his 2012 presidential bid are to be believed, “Russia without Putin” would disintegrate into an apocalyptic wasteland, sliced up and devoured by separatists (with the help of Europeans and Americans). It’s not surprising, then, that Cameron would have asked Putin’s advice in dealing with break-away regions.

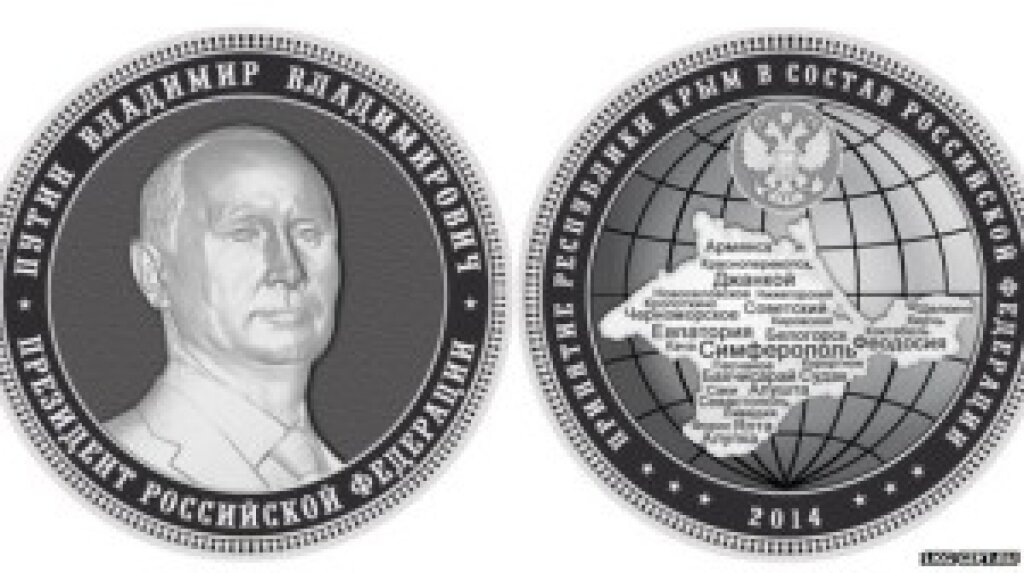

Cameron’s alleged (though unconfirmed) solicitation of Kremlin wisdom took place in January, in other words, before Putin invaded Ukraine, staged an illegal referendum in Crimea, annexed the peninsula, and began sending Russian troops to help separatists in Eastern Ukraine. However, recent Russian actions shouldn’t make the world’s leaders less eager to ask for Russian anti-separatist advice, but more eager. Breaking Crimea off of Ukraine, after all, yielded a Colbert-style bump to Putin’s approval rating, which remains around 85%. So maybe it’s time we all listen up and take some advice from a leader who knows how to keep his country together by breaking other ones apart.

Flesh and Bones

As everyone loves to point out, Russian leaders have been strong for a long time. Back in the good old days, Russian unity wasn’t achieved through nationality or religion or even law, but through autocracy, which stood above them all. As the territory of the empire expanded outward from Moscow at a staggeringly rapid pace between the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, it came to include a vast array of ethnic groups, religions, and cultures. The tsar held it together. A political consensus emerged (though no polling data have remained) that no other state form could possibly hold such a huge and diverse country together. If longevity is any indication, it worked pretty well. Until, of course, it didn’t.

Once Bolsheviks killed the autocrat in 1918, the state needed a new basis for unity, a need made desperate by Russia’s vicious Civil War that broke the empire into dozens of “independent” pieces. There were a number of tactics used to reunify the state, such as (paradoxically) promoting autonomy for national minorities, mobilizing working classes, and lots of guns. It’s not irrelevant that the word “Union” featured prominently in the country’s new name. But the Soviets didn’t abandon the principle of strong leadership: union was forged by a singular party, at the head of which stood a strong leader.

It’s true that there are similarities between Russia’s past and present. However, to say that Putin is reinstating an autocracy (he’s not), reconstituting the Soviet Union (he’s not), or, somehow, both at the same time, is to miss the point. Russian state power today draws freely from it’s past but in doing so it is constituting something new, a union spanning time, so to speak, as well as space. “United Russia,” Putin’s nearly hegemonic though nevertheless democratic political party which combines tsarist symbolism, Soviet mobilization tactics, and electoral politics, is one example of this. The annexation of Crimea, seen as simultaneously a reenactment of Ivan the Great’s sixteenth century “gathering of Russian lands,” a step toward restoring Soviet brotherhood, and an emblem for increasingly virulent Russian nationalism, is another. Putin’s sky high poll numbers – and, more than that, the fact that poll numbers matter – should be proof enough that the unity-inspiring power of Putin is not just a rehash of the past.

It’s not that we in the West haven’t done anything to mitigate separatist tendencies. We have devised our own ways of telling ourselves that we’re unified, like the constitution, and putting a U. in front of S.A. (I’m looking at you, Vermont). As an American, just telling someone what country you’re from is a performance of state cohesion. There was also the matter of the American Civil War. But lately we’ve resorted to posting memos on the White House blog when separatists strike. Lame.

The British rely on equally soft measures: Prime Minister Cameron is letting the Scottish people decide their own destiny, hoping that his passionate reminders of the United-ness of the Kingdom will convince the “Yes” voters to change their minds. But these are abstract ways of bringing about unity. They’re nothing like the unity that can be effected by a good, strong, flesh-and-bones leader.

Crime Time

Sadly, telling people that they are united doesn’t always work, which is why you need a back-up plan. Criminalizing talk of separatism is a good one.

Here, too, we can learn from Putin. Thanks to a robust new law criminalizing calls for separatism that he signed last December, the term “separatist” in Russia has become a useful shorthand for not obeying the state. An owner of a fish processing plant in Murmansk named Mikhail Zub, for instance, was recently accused of separatism. Zub can no longer buy enough fish to keep his plant open because of this year’s sanction-wars between Russian and the West. He filed a lawsuit against the Russian government to try to get permission to buy much-needed salmon from Norway. Despite the fact his course is a legal one, he’s not optimistic. “I am now considered a separatist,” he told the Moscow Times, “one who goes against a uniform government policy.” You see, anyone can become a separatist, even if he’s not.

The UK has decided not to go the criminalizing route, unfortunately for Scotland’s “No” campaign. However, there are hopeful signs that at least some Americans are in favor of making separatism a crime. For instance, eleven thousand or so anti-separatists worked themselves into a tizzy in 2012 in response to the petitions submitted to the White House for the right to secede. They called on President Obama to sign an executive order that would strip citizenship from the people who signed the petitions and then deport them. This is a good start.

Readers who happened to see these anti-separatist petitions will know they were meant to be hilarious (dumb ol’ Texans). But that doesn’t necessarily diminish their potential for bringing about much-needed change. Everyone knows we shouldn’t be having conversations about self-governance. So those clever calls for exiling people who do are a good way to shame them into shutting up. Plus, maybe someday we really will have laws that criminalize petitioning our elected leaders. That would be funny.

Outside In

There’s one more thing we can learn from Putin, which brings us back to Ukraine. The formula is: support separatism abroad to help fight it at home. Some might think it supremely ironic that Putin, who has been so successful at neutralizing separatists and plucky regional elites, should so blatantly sponsor separatism in neighboring Ukraine. But it actually makes quite a bit of sense.

For one thing, Putin knows how important regional cohesion is to the stability of a state. His presidencies have been characterized by, among other things, working to more closely unite the country in order to shore up state power. So he knows how separatism works from the inside out. His destabilizing actions in Ukraine, therefore, are a matter of reverse engineering.

For another thing, invasions can rally public support at home. Leaders have known this for a long time, which is one of the reasons empires wage wars. It can get risky not to be energetically committed to your country when a foreign invasion is underway (“United We Stand”?). In the case of the Crimean peninsula, the 90% majority who supposedly voted for union with Russia could easily serve as an inspiration for would-be separatists inside Russia to fall in line (fish packers obviously require different kinds of persuasion). I would imagine that Putin hopes the pro-Russian separatists he’s supporting in Eastern Ukraine are having a similar effect. How could you want out of the Russian state when so many people want in?

Every country fears the loss of political and social cohesion inside its borders. Over the years, Russia has developed some useful methods for keeping that from happening. Since it’s way too much work to carry on civil debate about the nature and shape of our political unions, maybe it’s worth considering some of the Russian solutions. There’s always room for improvement.

Now, if only there were a peninsula somewhere south of California we could annex…