José Alaniz, professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures and the Department of Comparative Literature (adjunct) at the University of Washington, Seattle, has published two books: Komiks: Comic Art in Russia (University Press of Mississippi, 2010) and Death, Disability and the Superhero: The Silver Age and Beyond (UPM, 2014). His research interests include death and dying, disability studies, eco-criticism and comics studies. Current book projects include Resurrection: Comics in Post-Soviet Russia. His own comics have appeared in The Stranger, the Seattle anthology Dune and Tales From La Vida: A Latinx Comics Anthology.

The rise of a viable comics industry in Russia, more or less congruent with Vladimir Putin’s third term, has seen a handful of works examining the country’s troubled past. Some comics position themselves as introspective views into said past, others as exemplars of a unique art form. A very few do both.

Russian comics artist Olga Lavrenteva reflects on how graphic narrative uniquely represents Russian history, popular memory and trauma — and what that fact says about Russian comics themselves. A 2009 graduate of the Art Department of St. Petersburg State University with a degree in graphic design, Lavrenteva was welcomed into the ranks of St. Petersburg’s Artists' Union in 2013. She has released four long-form works of comics, including the harrowing biography Survilo (Boomkniga, 2019). Based on her 93-year-old grandmother’s experiences during the 1930s Stalinist repressions and the Siege of Leningrad, Survilo deserves to be called “the Russian Maus.”

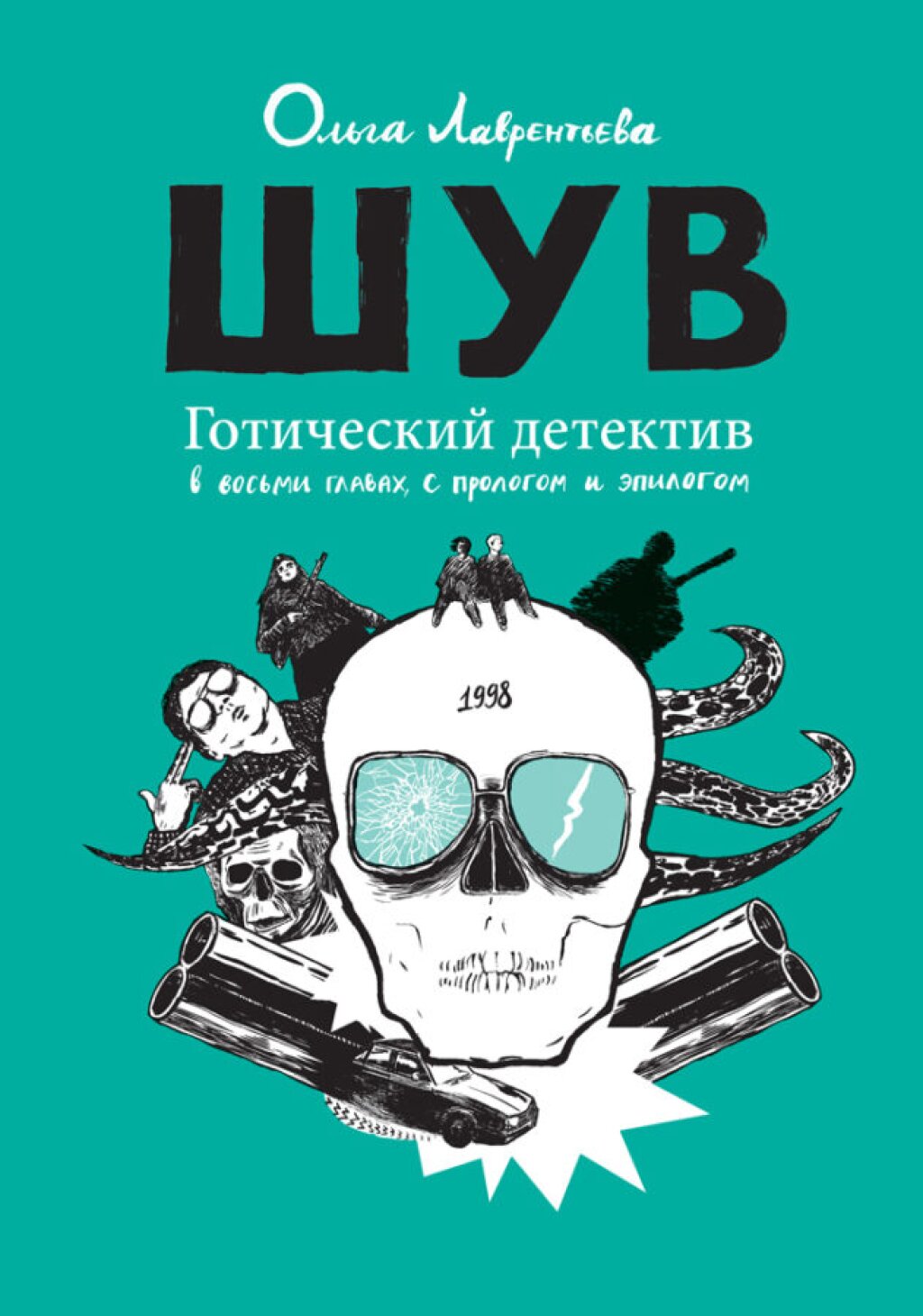

Lavrenteva’s “gothic detective” graphic novel ShUV (Boomkniga, 2016) recollects and reexamines a much more recent national trauma: the 1990s.

The plot involves a brother and sister of tender age living at their dacha late in the decade. The siblings fill their days with imaginative and horribly sadistic games: they role-play Chechen terrorists, Russian dictators, prostitutes and dead-ender soldiers, subjecting their stuffed toy bears and Barbie dolls to mock torture and executions (in cringingly hilarious scenes that evoke a gory, R-rated Calvin and Hobbes).

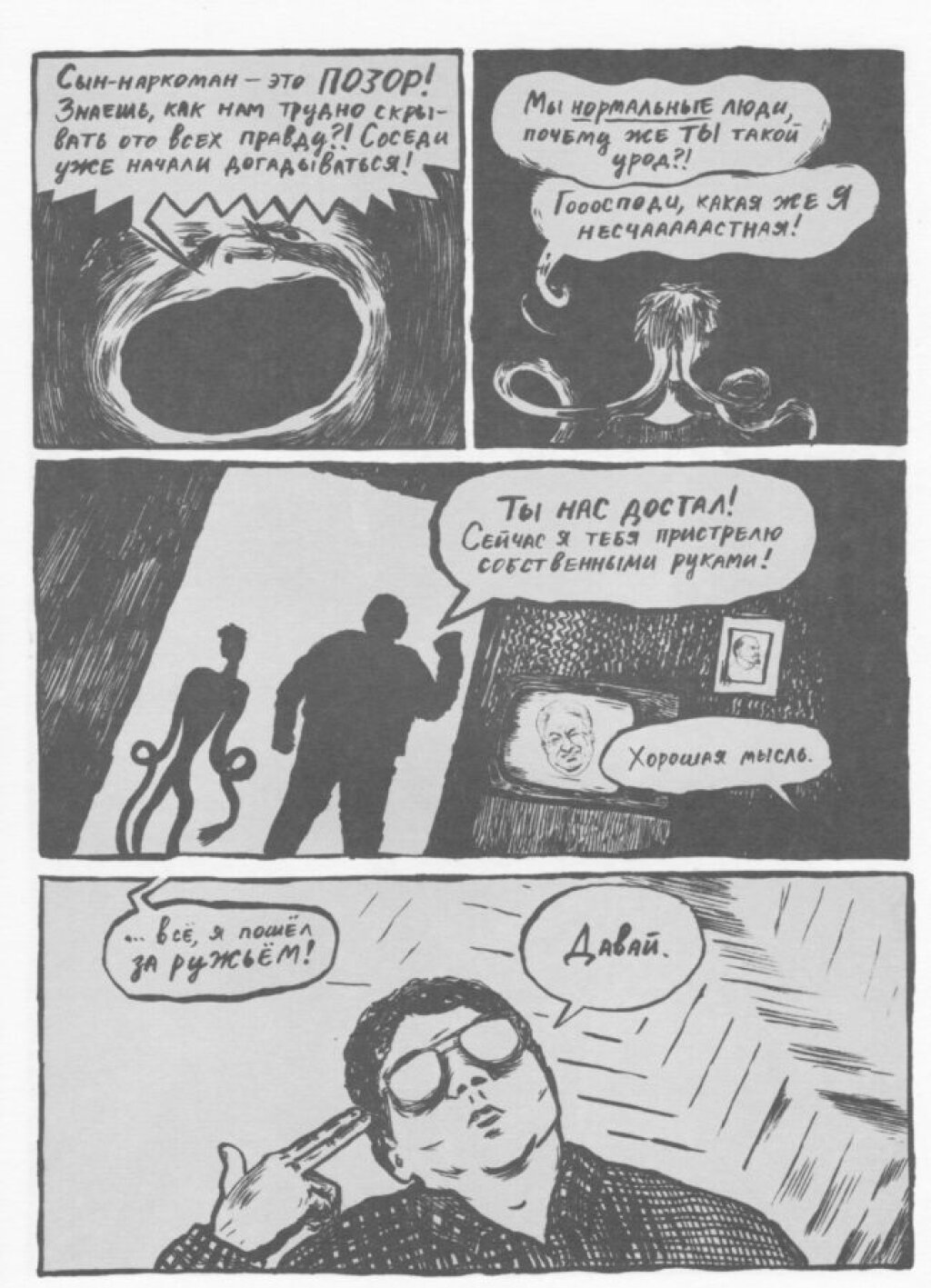

Clearly, the unnamed young siblings are reacting to a vision of Russia brought to them by television and newspapers — a world full of sexual violence, mafiya hits and war. This was the lurid mediated reality for Pelevin’s Generation ‘P’ in the 1990s, whether on the news; in popular fiction genres like the boevik (action story) and detektiv (crime novel); or the movies (where chernukha ruled the roost). For the kids, though, all this bespredel merely serves as raw material for their fanciful, blood-curdling play.

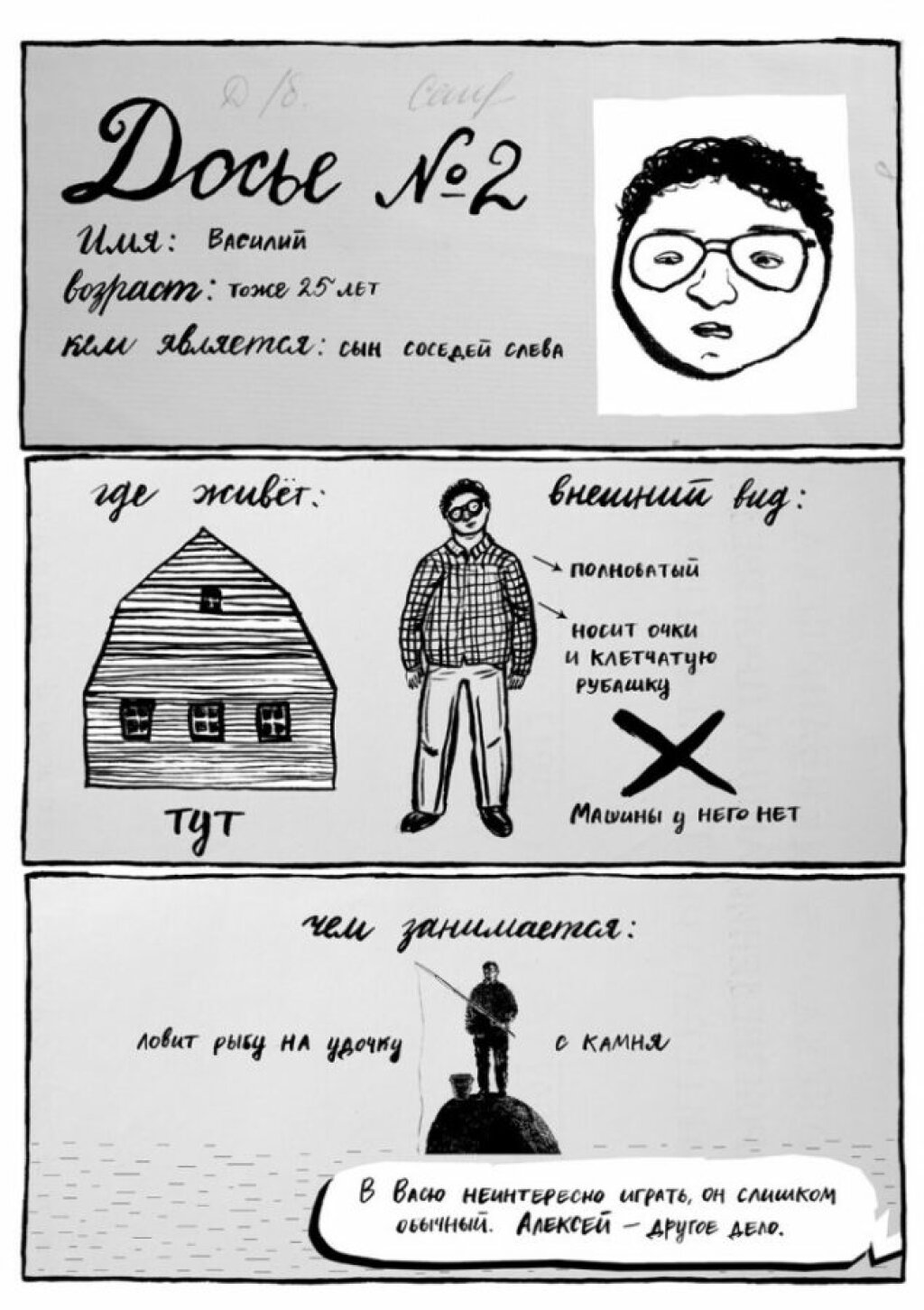

But nothing fuels the siblings' imaginations like the real-life suicide by gunshot of their dacha neighbor Vasya, a pathetic schlub they later learn was a drug addict.

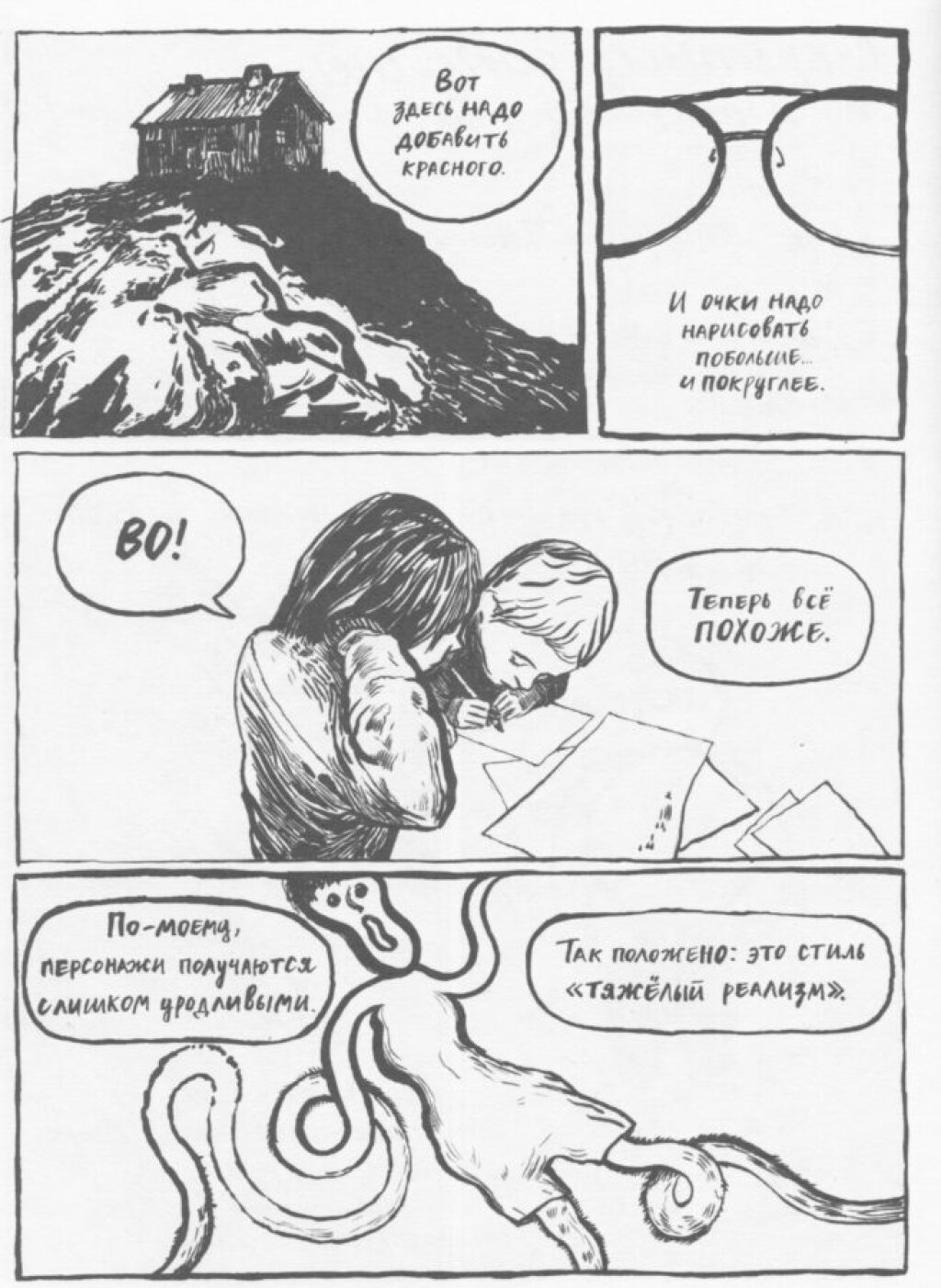

Their stuffed toys can’t compete with another medium — comics — as a vehicle for their expressive élan. The boy and girl start making picture stories about Vasya’s death, which soon take on a whole new cast when they come to suspect the young man was actually killed by his wastrel parents, who have covered up the crime. Their “super secret” comics, housed in a cheap green notebook, take on the significance of a “holy manuscript” as they wildly speculate about how the killing occurred.

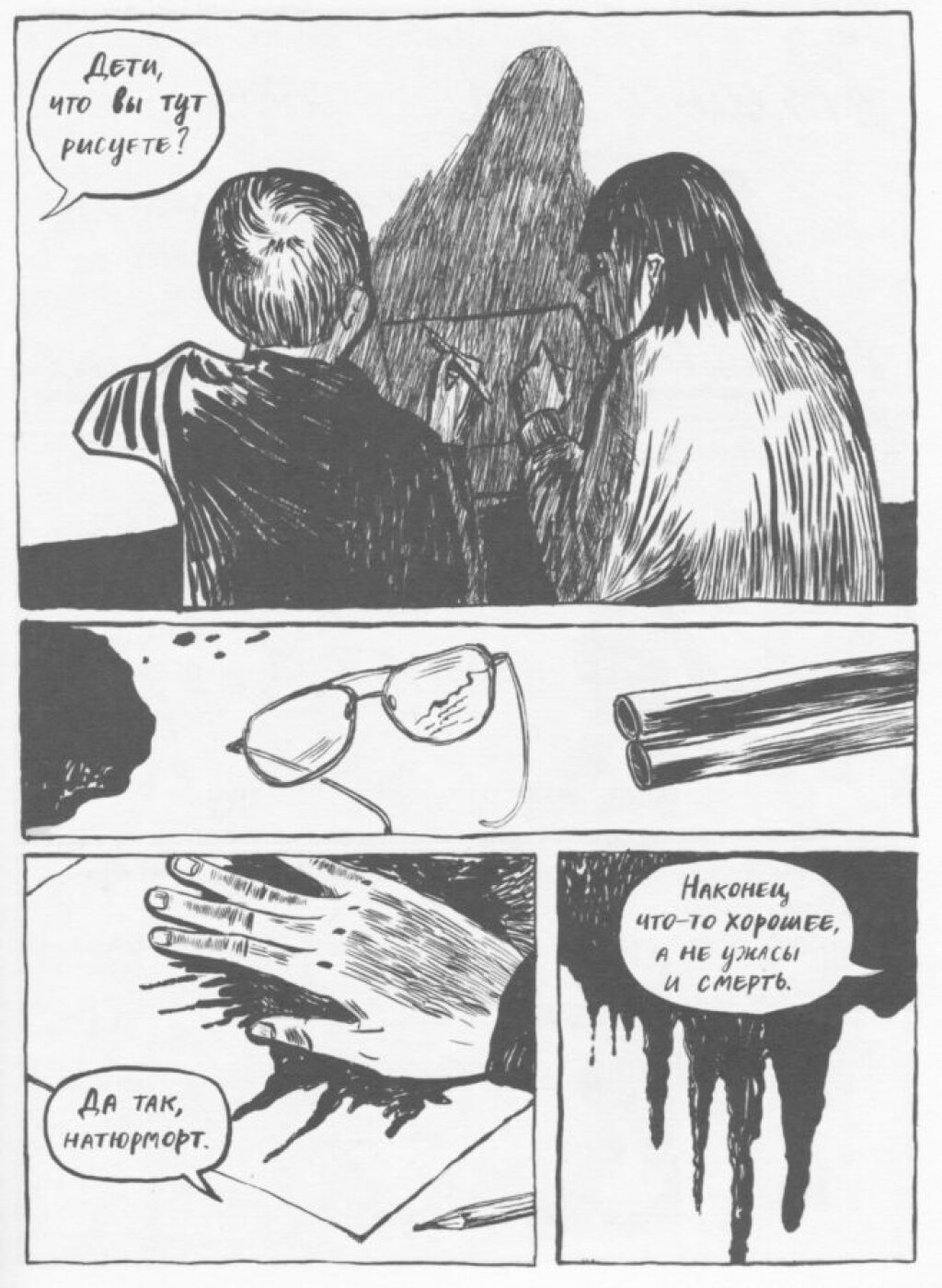

Equal parts transgressive, funny, and tragic, these comics-within-the-comic are also, as Alexei Pavlovsky puts it, “comics about comics” (“Russkaia gotika,” my emphasis). Our young authors endlessly debate the form and content of their ever-evolving opus, which redounds to the construction of ShUV itself — making for an intensively self-reflexive reading experience: “Here’s the blackest panel,” a text box announces, over just that. And Lavrenteva’s kids have a keen eye for style, too: when one of them objects, “I think the characters look too ugly,” the other replies, “That’s how it’s done: this is in ‘hard realism’ style."

At another point, one of them interjects: “That’s it, stop! That’s enough snakes. Otherwise the comic’ll turn out too gross.” This is Cortázar or Borges by way of Edward Gorey's Gashlycrumb Tinies. And, of course, the more mayhem the better. A panel of Vasya with his brains spilled onto the floor prompts one of the siblings to cry out, “Whoa! This comic is cooler than the last one.” Variations on the sound effect BA-BAKH (KABOOM!) repeat throughout the work, as the kids depict different versions of the supposed murder over and over, escalating the gore with every pass.

Lavrenteva heightens the mood of impropriety by conveying to the reader a sense of being inducted into the children’s private world: their intimacies, verboten pleasures and hiding places, concealed even from their parents — especially from their parents. The “sacred text” of their comics is a box with many locks. Even the title ShUV functions as a code that needs to be deciphered; it’s an abbreviation for the kids’ hypothesis, made up of the letters Sh, U and V: “Shlomov Ubil Vasyu” (Shlomov Killed Vasya). The reader, perhaps disconcertingly, enters an unseemly secret society, a puppet theater of cruelty.

The author here is primarily targeting the 1990s, a decade many Russians associate with unmitigated disaster and would rather forget (and also a decade many in the modern Russian comics industry dismiss outright as a lost age). Lavrenteva lays the references on thick: apart from the mentions of Chechnya and the mafiya, we see Yeltsin on TV, while Lenin’s portrait still hangs on the wall; Criminal Russia, a blood-and-guts-filled true crime show of the era; a bookshelf well-stocked with Stephen King horror novels, whose translations won over many fans in that decade, and which Galina (Vasya’s mother) reads obsessively. It’s no surprise that the siblings label their third comics story “sovershenno sekretno [top secret]" — a plausible descriptor, but also the name of a sensationalistic 90s tabloid.

Ultimately, ShUV’s references, devices and transgressions come to implicate the reader in the excesses and dehumanization of so much Russian media of the Yeltsin era, when the country was veering from the state control of the USSR to the raucous “freedom” of first-stage capitalism. It’s all sick fun — but at what cost? The graphic novel forces a confrontation with the legacy of a terrible time and its unacknowledged psychic scars, with how the survivors of the 90s (failed to) process the horrors of their age, carrying them forward through life.

Lavrenteva is further asking: why do comics excel at thrilling impressionable young people with Grand Guignol-type fare? Could there be anything redemptive in all the carnage? (We should hope so.) I would say yes: we could read ShUV as we do the EC horror comics of the 1950s — as grisly entertainments steeped in socially-conscious political critique. Others, like Gerard Jones, have argued for the psychologically beneficial effects on children of comics-based violence and “monstrous” representations. But ShUV’s own answers to the questions it poses are both more profound and more disturbing.

As Pavlovsky perceptibly argues, through their endless production of words and pictures, the kids themselves become Vasya’s symbolic killers (“Russkaia gotika”), tormenting his image over and over, just as they do their hapless stuffed toys.

But in the process, somehow, through art and imagination, “Vasya” takes on a bizarre afterlife — as indeed do the 1990s themselves within ShUV’s pages, with all their humiliation and horror. This makes ShUV, in part through its mise-en-abyme structure, a graphic novel that insistently interrogates its own medium’s Baudrillardian representation of death, its simulacral capacities to both take “life” and to give it back.

The kids’ version of Vasya is always dying — another way of saying he’s always alive, ready to die again. This idea in turn leads us to consider how graphic narrative, among the most interactive of arts, allows readers to mentally inhabit imaginary characters (perpetrators as well as victims) up to and past the point of death; in other words, how identification functions in comics. Finally, the novel asks us to mull how comics participate in the enjoyment which, however guiltily, derives from the second-hand consumption of human misery. In Lavrenteva's remarkable book, as in any black and white comic, spilled ink looks just like blood.

Through these ambitious aims, which earned ShUV the 2017 Malevich Award for Best Script and its author comparisons to Nikolai Gogol (Bondareva, “Chto takoe”), ShUV blazes a trail for graphic narrative in Russia even as it looks back at a traumatic period of recent Russian history. Its plot, centering on the exposure of children to adult material they cannot really understand, and which they then sublimate into scandalous art, allegorizes the journey of Russian comics themselves in the troubled post-Soviet era.