On Monday, October 29th The Jordan Center hosted Professor Nariman Skakov for his talk titled “Socialist Orientalism: Aleksandr Rodchenko’s and Varvara Stepanova’s Ten Years of Uzbekistan.” Nariman Skakov is an Assistant Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at Stanford University, and has published numerous works on 20th-century Soviet and Post-Soviet literature and culture, with his current research focusing on the intersection of Soviet Modernism and the Soviet Orient. The talk, part of the Occasional Series, was introduced by Assistant Professor of Russian at New York University Rossen Djagalov.

Professor Skakov began the talk by recalling a line from a letter Aleksandr Rodchenko wrote to his partner Varvara Stepanova during his attendance of the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative of Modern Arts in Paris: “The light from the east is not only the liberation of workers; it is the new relation to person, to woman, to things; our things in our hands must be equals, comrades, and these blackful and mournful slaves as they are here,” the quote reads. This quote, according to Skakov, evokes an “emancipatory” rhetoric that proposes a new “affective” relationship with the “world of things.” Seven years prior, a fragment of the same phrase was used by Joseph Stalin in an article he published in “Pravda,” that characterized the West as a “breeding ground of darkness and slavery,” and proposed a re-orientalization towards the East for the socialist movement. For both of these revolutionary figures, the East served as a new point of origination, where the “sun rises.” But this specific perception of the east, according to Skakov, experienced a “modification” in the 1930s. “Russia, as an oriental luminary, would re-orientalize towards its own orient – the republics of Central Asia – assuming a role as the enlightening Westernizing force, while building socialism in one country,” Skakov said. Professor Skakov’s research, which deals with Rodchenko’s work over the course of this decade, argues that the Constructivist movement “didn’t just yield to external political pressure of the epoch, but also adopted principles in line with the ideological demands of the epoch.”

Following the introduction, Professor Skakov outlined the key features of Constructivism during its most prominent decade of the 1920s. The movement set out to manifest the “communist expression of material structures,” to disrupt sets of binary pairs such as art and reality and contemplation and production. The movement saw the factory as a collective enterprise and as the antithesis to bourgeois individualism, while both Rodchenko and Stepanova’s obsessions with the object, according to Skakov, “repudiated any form of artistic decoration.” The phrase “material-formation of the object” was key in understanding Constructivism’s early impulses. Citing scholar Maria Gough, Skakov explained how the Constructivist notion of “factura” experienced a transformation from an “anti-authorial materiological determination” to a more “conventional functionalism”.

When Constructivism’s influence began to wane, the leading avant-garde theorist Viktor Shklovsky began to promote similar ideas regarding materiality. According to Professor Skakov, Shklovsky transitioned from the perception “of materials that passively await to be modified” to a focus on the “human artistic engagement with tools.” “The defamiliarized thing of the 1910s as an object of perception,” said Skakov, “was replaced by the artifact, whose materiality was pronounced so that its material structure could be better apprehended in the 1920s.” Shklovsky was preoccupied with the “concrete material perceptibility” as not a “mere abstract perception”. The inherent qualities of the objects, and the perception of individuals engaging with the object became the focal points of Shklovsky musings. The theorist characterized this human-object relation as a “prosthetic alliance.” To help understand Shklovsky’s conception of this new human-object relationship, Skakov cited the following passage from a letter Shklovsky wrote: “A tool not only extends the arm of a man, but also makes him an extension itself… Things make of man whatever he makes from them.” In the final segment of the passage, Shklovsky exhibits a certain urgency in mankind’s responsibility in mastering the machine. Each of these machine-man pairs, Skakov said, “actualize each others capabilities.”

Skakov segued his talk into an analysis of the photomontage, and a major theoretical shift that characterized Rodchenko’s work between the decades of the 1920s and 1930s. Rodchenko’s camera tilts performed complex functions: to reorientalize the gaze, and, as Rodchenko himself put it, to “remove the cataract from the eyes.” For Rodchenko, the “lens of camera is the pupil of the cultured man in socialist society,” and the camera a tool for visual reeducation – an assertion that “acknowledged the restraints of reality.” However, by the 1930s, as photomontage became a tool for political propaganda, the aim of visual reeducation was discarded. The Socialist Realism style used photomontage to reinforce the influence of the real object, while eroding the Constructivist principles under which the practice was initially created. For the Stalinist psyche, explained Skakov, “the construction of a socialist society left realm of reality” and wandered into realm of representation. The utilitarianism that characterized Russian Constructivism entered a “symbolic field.”

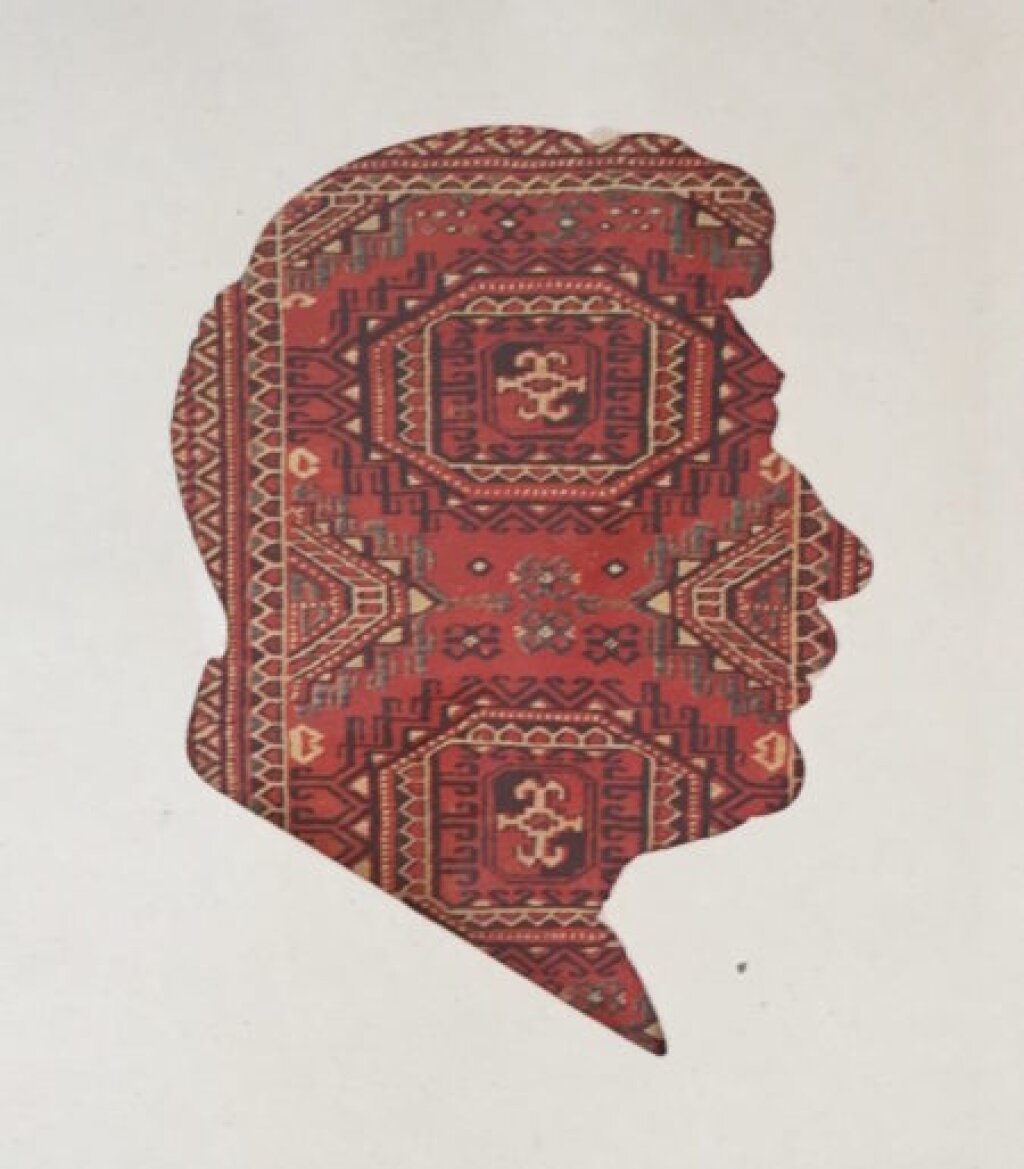

This particular theoretical shift, argued Skakov, is most evident in Rodchenko and Stepanova’s design of the “Ten Years of Uzbekistan” album. The album was commissioned and produced in 1933, with the intent of producing a luxurious folio to commemorate the tenth-year anniversary of the Uzbek Socialist Soviet Republic. At the time, the Central Asian republic was considered “an exemplary space” for manifesting the Socialist goal: the inherent emptiness of the land was filled by accelerated construction as a result of political decrees. By the 1930s, however, this newly inhabited space also “needed to be filled with symbolically meaningful content,” and this is where Rodchenko and Stepanova’s project came into play. The album, explained Skakov, was an “impressive graphic design achievement” that blended photo collage with portraits of the political elite that gave rise to the republic and textual inserts. These “epic visual compositions” were able to overcome the spatial limits of the page: the book, which was physically very large, was comprised of fold out pages. The images depicted a sort of “typographic oriental carpet”, that presented Uzbekistan as both an “exotic fairytale land and an advanced socialist topos.” But Stalin’s purges added yet another interesting aesthetic element to the book, as many of the individuals whose photographic portraits featured in the book fell out of favor with the Stalin regime. Due to the fact that it was illegal to possess books with full photographs of political personnel who the state deemed an enemy, Rodchenko and Stepanova resorted to covering these portraits with ink blotches. According to Skakov, this particular stunt evolved into a radical aesthetic gesture: the ink stains simultaneously conceal the victims, while revealing the profound horror of removing somebody from history. The “the dark void,” Skakov said, “is an arresting representation of an all-consuming animal fear,” that competed with Malevich’s “Black Square” in its representational radicalism. The portraits themselves were shot from a straightforward angle unusual to Rodchenko’s earlier work.

During the height of Constructivism, Rodchenko urged photographers to capture the full “conception” of an object by shooting it from every angle possible. But his reorientalization, and exposure to the fringes of the country, prompted him to readjust his theoretical apparatus. The Soviet orient, according to Skakov, was a reservoir for an unfamiliar experience that didn’t necessitate a special “rakurs” (angle), but rather, it needed a mode of representation that made it familiar and accomplished a “cognitive closure.” His use of rakurs, however, didn’t altogether disappear, as examples of it can be found in the book: photographs of both factories and factory workers are taken from various, unconventional angles. Likewise, Rodchenko’s use of color filters in the photographs featured in the album echoes his famous monochrome series. Stepanova’s theoretical contributions are also crucial to the foundation of this album: multiplicity of color in photographs and a single dominant figure within the photograph are just a few examples of Stepanova’s conceptual contributions. Likewise, Stepanova drew from her experience with handwritten books and “hard material,” such as with the Zaum book, to assemble this album from an assortment of unconventional material. In its entirety, the album reveals a “peculiar blend of modernism and socialist realism.” While the formal language of the avant-garde remains in place, albeit slightly modified, the clarity in line with the official style of the Soviet Union is also very present. The book aspires not for representation, but for “presentation and display as hyperreal, future oriented” entities.