Christopher Tremoglie attends the University of Pennsylvania, where he is majoring in Russian and Eastern European Studies and minoring in Political Science.

Early Soviet cinema pioneered the use of film as propaganda rather than entertainment. From the regime's inception, the Bolsheviks saw cinema as a fruitful avenue for persuading Russians to adopt Soviet ideals.

During the Bolshevik Revolution and Civil War, for example, Soviet leaders needed to rapidly drum up support for the revolutionary cause from a largely illiterate populace. Given the scarcity of celluloid in Russia at the time, Soviet filmmakers had to be inventive, ensuring that each move had instructional as well as entertainment value. To this end, they developed new and innovative techniques to stimulate their audiences. Many of these techniques, chief among them montage, remain in use today — for example, in the television series Game of Thrones.

Prominent Soviet filmmakers Sergei Eisenstein (1898-1948) and Lev Kuleshov (1899-1970) developed many methods for stimulating the viewer's emotions, which facilitated the promotion of Soviet ideology through the use of aesthetically pleasing material. Considered conventional today, these developments were groundbreaking in their time. Then, as now, the pace and rhythm of editing, as well as musical scores, were key to stirring audience emotions.

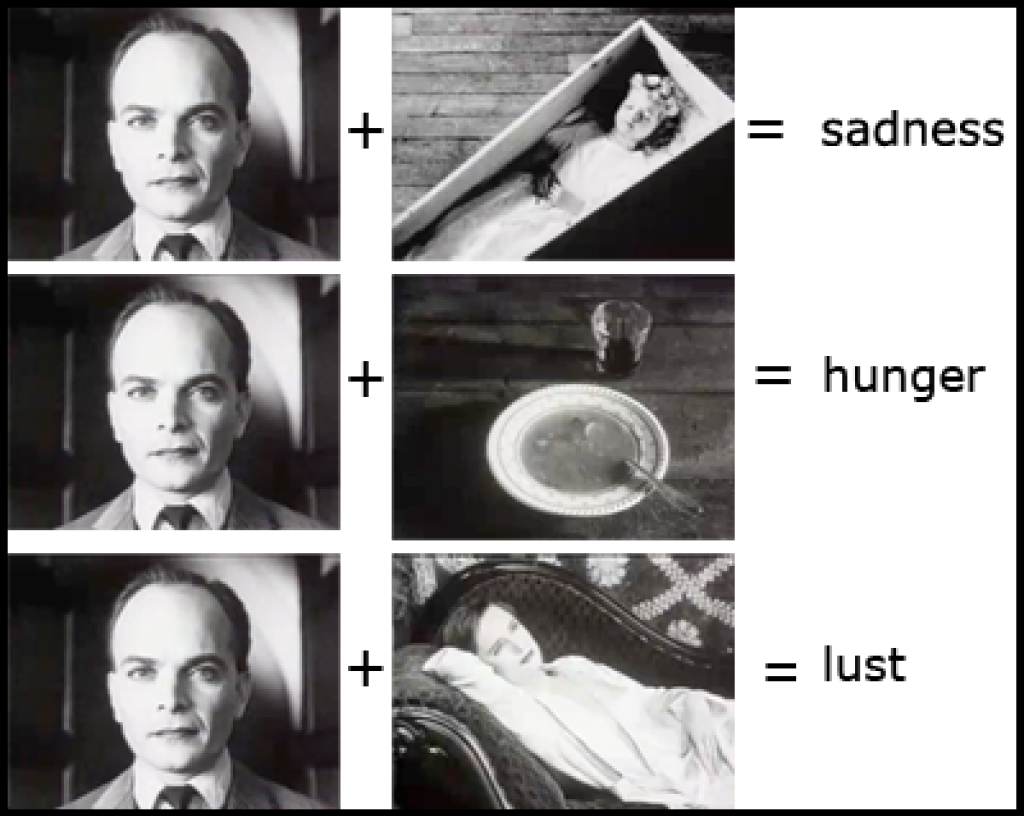

Kuleshov, for instance, realized that it was possible to string together emotional responses through a strategic sequencing of shots. In what became known as the Kuleshov effect, the filmmaker followed shots of an actor, whose facial expression remained the same, with one of three different images: a girl in a coffin, a hot plate of soup, or a pretty woman lying on a couch. The audience's reaction to the three pairs of images revealed their "collective" value: depending on the image that followed the shot of the actor's face, he could be made to look either sad, hungry, or lustful.

Source: http://www.elementsofcinema.com/editing/kuleshov-effect-and-juxtaposition/

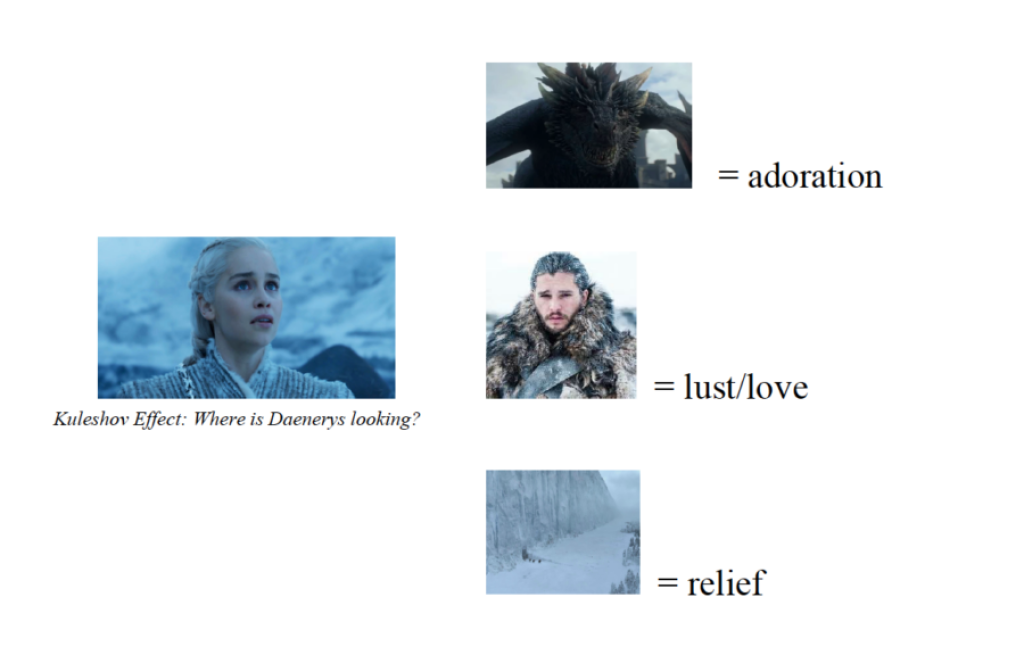

The Kuleshov effect is used almost every episode of Game of Thrones to great emotional effect. For example, “The Dance of Dragons” (Season 5, Episode 9), Daenerys Targaryen watches two men fight in a gladiator pit. Daenerys has a frantic, worried and concerned look on her face over the fate of one of the combatants, her old friend Jorah Mormont. The juxtaposition of shots of Daenerys’ face and Jorah fighting conveys to the audience that she is worried about Jorah. The audience, which is presumably already attached to Daenerys, thus becomes emotionally invested in the fate of her friend. The Kuleshov effect dictates that the shot of an unchanging expression on Daenerys’ face, mixed with shots of three other images, would result in the audience interpreting her feelings in three different ways:

Another enduring technique of early Soviet cinema is montage, especially as used (and theorized) by Sergei Eisenstein. Eisenstein famously used montage in two of his most important works: Strike (1925) and October (1928). In the former film, a sequence in which cows are slaughtered is cross-cut with shots of workers being murdered by the provincial military. This type of montage, which privileges images with significant political, aesthetic, or social associations, came to be known as “intellectual montage.” Eisenstein, like Kuleshov, sought to generate emotional reactions in the viewer through a panoply of techniques, including montage, stretch time (in which an action sequence is "stretched" far beyond its "real" duration), manipulation of light, and tertium quid (in which an indistinct "third thing" is associated with two known elements).

In Game of Thrones, one example of Eisenstein’s influence is Arya Stark’s training montage. In this sequence, a blind Arya submits to vicious training by an assassin known as the Waif. Early shots in the sequence — at which point Arya is a novice enduring regular beatings — are rather dark. As she improves, more and more light is inserted into each shot. When Arya finally emerges victorious, the screen is filled with light. The progression from darkness to light in the training sequence follows Arya's improvement and elicits the audience's sympathy. This scene draws deeply on Eisenstein's characteristic use and manipulation of light in his films.

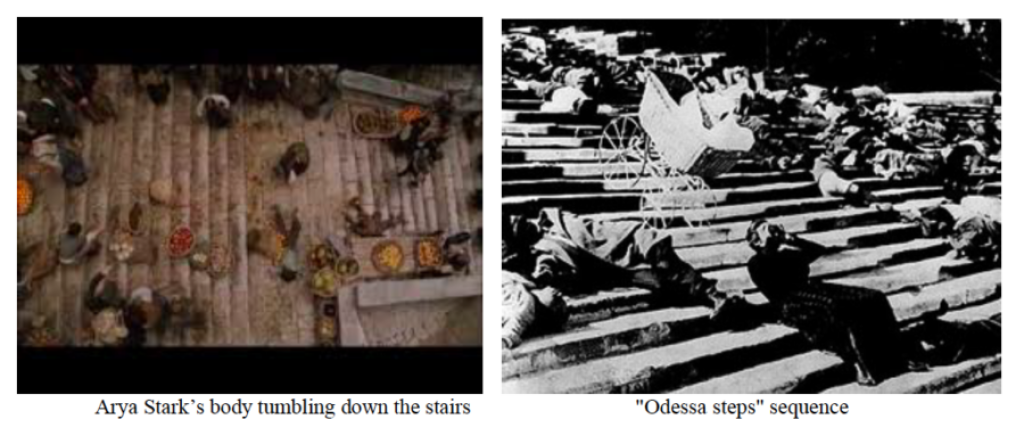

Another example of Eisenstein’s influence in Game of Thrones occurs in the episode “No One” (Season 6, Episode 8), where the Waif chases Arya. This scene culminates in Arya falling down an outdoor flight of stairs. The reference to Eisenstein is unmistakable: the scene recalls the famous “Odessa Steps” sequence from Battleship Potemkin (1926). Instead of the stroller, however, we have Arya Stark’s body rolling down the stairs, with the Waif replacing Eisenstein's soldiers. Though Game of Thrones was filmed nearly a century after Eisenstein's iconic film, it uses many of the same techniques as Battleship Potemkin, especially graphic images, rhythmic montage, and dramatic shifts from wide shots to extreme close-ups.

We can observe montage and tertium quid in both the “Battle on Ice” scene in Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky (1938) and the “Frozen Lake Battle” in Game of Thrones (Season 7, Episode 6). Both scenes depict large-scale, important battles against an intimidating adversary fought on a frozen lake. Nevsky’s army faces long odds against the Teutonic knights, with their very existence hanging in the balance. The same holds true for Jon Snow in Game of Thrones. Both scenes use intellectual montage and tertium quid to emotionally bind the audience the characters' fates.

As the use of Soviet-style visual techniques would suggest, Game of Thrones is not without propagandistic purpose. In the Season 7 finale, “The Dragon and the Wolf,” Jon Snow declares: “I’m not going to swear an oath I can’t uphold. Talk about my father if you want; tell me that’s the attitude that got him killed. But when enough people make false promises, words stop meaning anything. Then there are no more answers, only better and better lies, and lies won’t help us in this fight.” This speech was later revealed to be metaphorical commentary about the election of Donald Trump to the US presidency. In an interview, the actor Liam Cunningham (who plays Jon Snow's top adviser) disclosed that the episode filmed just hours after Trump's 2016 victory. "That speech that Jon Snow gave about the nature of lies and what’s been said, and what happens if we don’t stick to our word," he said, came into being "on exactly the day that a certain POTUS was elected, and it had incredible resonance while we were filming it." It is not difficult to imagine Eisenstein creating a scene where Jon Snow's words are uttered as scathing criticism of tsarist rule or lying, greedy capitalists.

Many of the themes, techniques, aesthetic decisions, and concepts of Game of Thrones draw deeply on pioneers of Soviet cinema like Eisenstein and Kuleshov. Over a century of use, these techniques have demonstrated their flexibility and power, whether they are deployed to introduce Soviet viewers to Lenin’s New Economic Policy or chronicle the ascension of Jon Snow to “King of the North” for contemporary American television audiences. Far outlasting the regime they were developed to promote, montage, tertium quid, and other innovations of Soviet cinema continue to exert their transformative influence on entertainment cultures worldwide.