Mark Eliot Nuckols is an independent scholar and a translator for www.watchingamerica.com. He also translates for www.rightsinrussia.org, which is how he became interested in the Dmitriev case.

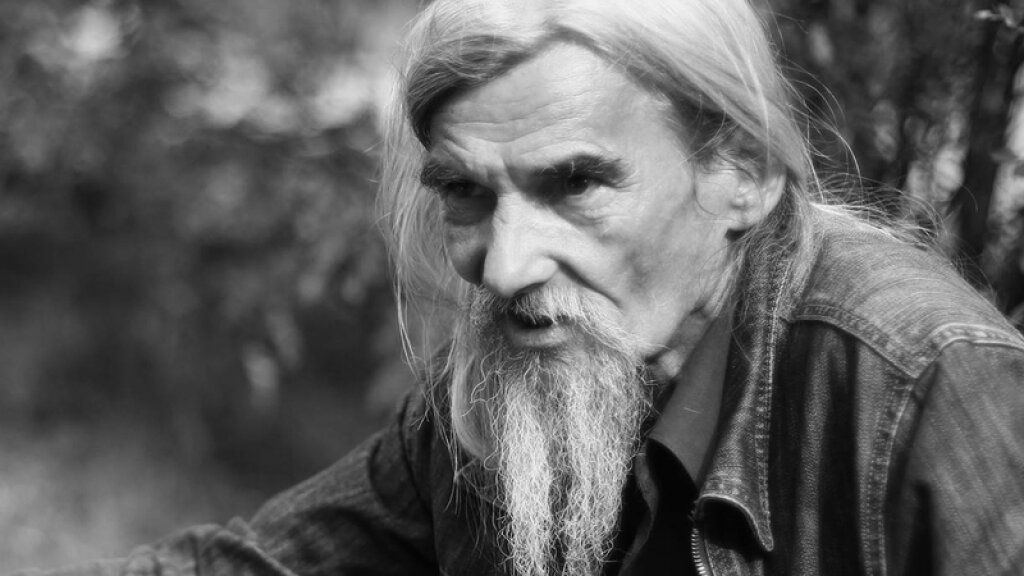

With his sunken cheeks, thick dark brows, and long gray hair and beard, it’s no surprise amateur historian Yuri Dmitriev’s friends often call him “Gandalf,” after the wizard from The Lord of the Rings. His eccentric behavior includes asking babushki in Karelian villages where it is that locals fear to tread – and going directly to those places in search of mass graves from the Stalin era. The methodical madness has led to the discovery of the remains of thousands shot in the woods of Russia’s northwest.

Dmitriev was born in 1956 in Petrozavodsk, 250 miles northeast of St. Petersburg and a hundred miles east of the Finnish border. he spent his first year in an orphanage before being adopted by a Soviet army officer and his wife. As a young man, he studied medicine but soon dropped out. He’s been in and out of work for much of the last three decades, taking jobs such as plumber, factory worker, and security guard.

After being briefly locked up over an altercation, he came back from prison with anti-Soviet views. During the late Gorbachev years, he began working for Ivan Chukhin, a deputy of the RSFSR Supreme Soviet and later of the State Duma, who was also the first chair of the Karelian Memorial Society. Memorial had been founded in 1989 to document Soviet-era repressions, memorialize the victims, and monitor human rights. Chukhin engaged in the work largely to rehabilitate his father, who had taken part in executions.

Through this association, Dmitriev took interest in three “quotas” or batches of political prisoners from Solovki in 1937, at the time of Stalin’s Great Purge. Solovki, once called the “Mother of the Gulag” by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, is on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea, some 250 miles north of Petrozavodsk. Originally a monastery, it was converted to a concentration camp in 1923. The three quotas of prisoners were taken aboard ships which were then deliberately sunk – or so it had been widely presumed until Memorial’s investigations.

Dmitriev spent a good part of the 1990s in FSB archives examining case files on purge victims. After finding gaps in the lists, he asked for protocols from NKVD “troikas” – special three-person tribunals created to act as judge and jury in rigged trials. Those documents contained confirmation that death sentences had been carried out. But Dmitriev wasn’t allowed to copy or photograph them. So he would spend all day in the archives, reciting the information into a dictaphone.

At night he would stay up late, fueled by coffee and cheap Belomor cigarettes, typing and correlating the troika protocols with lists of people purged. He’d then get four hours of sleep and restart the cycle. The amateur historian had little paid work, and when his daughter, Katya, asked about his obsession, he replied, “I don’t know who I was in my past life, but I’ve understood the reason I’m living today, and I know I have to do this.” With this sense of purpose, he singlehandedly created the most thorough published record of executions in the former Soviet Union.

As he spent winters in the archives, so he spent summers literally digging around in the Karelian forests. As an experienced tourist guide, he knew his way around. Much like Finland, located 100 miles to the west, Karelia is a land dotted with lakes. Petrozavodsk lies on the western shore of Lake Onega, in an area covered in pines and full of mosquitos, horseflies and gadflies. Dmitriev would often accompany Chukhin on expeditions, but this mentor died in a car crash in May 1997.

Less than two months later, undeterred, Dmitriev found an unholy grail.

On July 1, 1997, he explored woods not far from Medvezhya Gora, about three hours from Petrozavodsk at the north end of Lake Onega. Katya, twelve at the time, and two members of St. Petersburg’s Memorial Society were with him. Following an execution squad’s notes to a spot remote enough that the killings could be kept secret, they found large oval depressions.

Local authorities readily arranged for a unit of soldiers stationed nearby to help. Soon they were digging up skulls with bullet holes. Over the next several days, they uncovered nearly forty pits, which were eventually found to contain over seven thousand bodies. They decided to name the site Sandarmokh, from nearby “Sandarmokh common” on an old map.

The group held a commemoration at the site on October 27, 1997. The ceremony marked the sixtieth anniversary of the first executions held there — those of the first Solovki quota, according to Irina Flige, head of Memorial's St. Petersburg Branch. “In 1998," Flige noted in a 2017 interview, "at Memorial’s behest, the Karelian government and the Medvezhyegorsk District administration established a International Day of Remembrance here at Sandarmokh. Its date, August 5, marks the beginning of mass punitive operations of the Great Terror in 1937.”

The commemorations grew from year to year. Families came to create small shrines for relatives. Faces of the dead, on black-and-white photos pinned to the pines, now stare hauntingly into the deep forest. Local authorities have typically attended, and in 2010 Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill led a service for the departed. The governor had a road built to the site, and buses have been provided for attendees. The Karelian government awarded Dmitriev with a certificate of merit.

Increasingly, foreign delegations have attended the annual events, as there are fifty-eight nationalities represented by the victims, among them Poles, Finns, Georgians, Ukrainians, and Tatars. Monuments have been erected in numerous languages, with Catholic crucifixes, Finnish flags, Muslim crescents, and other ethnic and religious symbols.

But official support has dwindled rapidly over the past four years, and some Dmitriev sympathizers suggest that, with Russian nationalism on the rise, the site has become too non-Russian and non-Orthodox.

The first sign of trouble came in 2014, after Russia’s annexation of Crimea. The Ukrainian delegation refused to attend, and the Karelian government declined to provide a sound system. Still, Dmitriev gave a speech, which included criticism of Russian military actions in Ukraine. The following year, “a mad Ukrainian grandad from Lviv in a Ukrainian nationalist uniform came as part of the Ukrainian delegation.”

Then, in early 2016, regime-friendly media began circulating stories about Finnish units executing Soviet prisoners during the Winter War of 1939-40. That summer, the Russian Orthodox Church sent no representatives. In October, the Russian government designated Memorial a “foreign agent.”

And in December of that year, Yuri Dmitriev was arrested.