Stephen F. Cohen is professor emeritus of Russian studies at New York University and professor emeritus of politics at Princeton University. His books include Soviet Fates and Lost Alternatives: From Stalinism to the New Cold War.

Katrina vanden Heuvel is the publisher of The Nation. Her books include The Change I Believe In: Fighting for Progress in the Age of Obama.

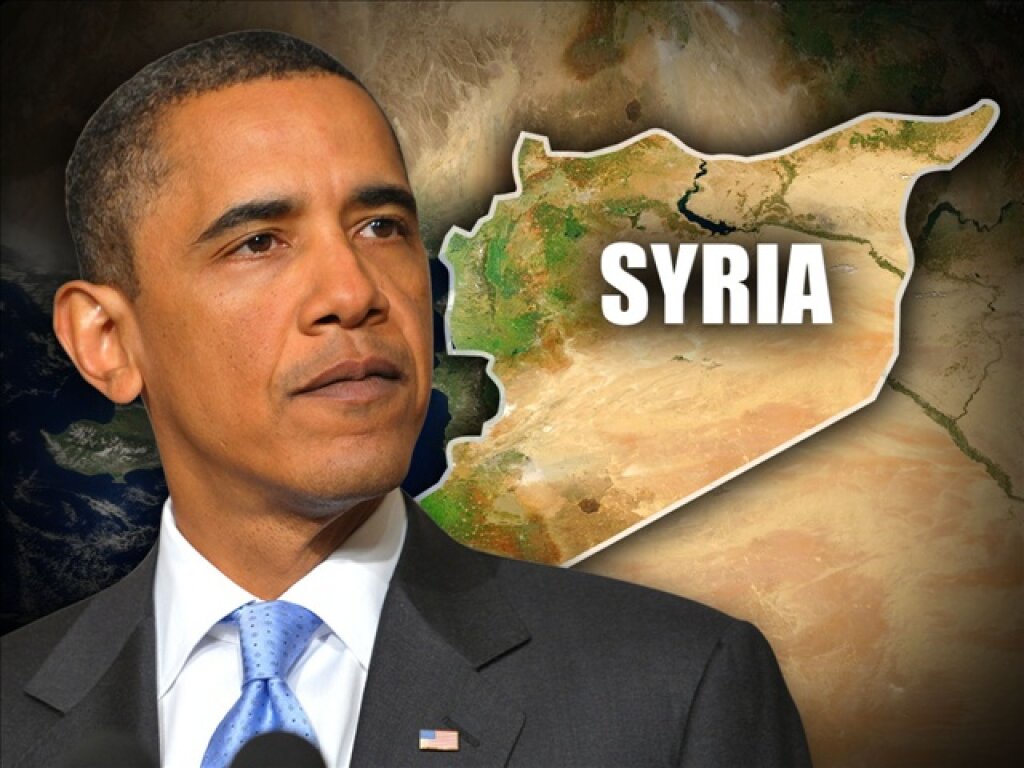

By claiming for weeks that “doing nothing” is the only alternative to a “limited” military response to the Assad regime’s reported use of chemical weapons in Syria—plainly stated, an illegal American war against a nation that has not threatened the United States—the Obama administration has continued Washington’s post–Cold War disdain for diplomatic solutions to international crises. It has done so in the same triumphalist, America-as-indispensable-nation spirit that inspired the Clinton administration’s bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999 and the Bush White House’s disastrous war in Iraq, both carried out without a UN mandate and over Russia’s protests.

But the Russian foreign minister’s September 9 proposal to put Assad’s chemical weapons under international control makes clear that a diplomatic solution to the Syrian crisis is eminently possible. President Obama called the initiative “potentially positive,” while Washington’s powerful pro-war and anti-Russian lobbies rejected it, as usual, as bogus and “very bad news.” In fact, the best approach has always involved both the UN Security Council and Moscow. Until now, the Obama administration has refused to pursue this path on the grounds that Russian President Vladimir Putin, whom it has repeatedly denigrated, would use Russia’s veto to block any military action—in effect, dismissing diplomacy before it is even tried.

The Obama administration should now fully endorse an emergency session of the Security Council without calling for immediate military measures. The session should begin instead with a full examination of conflicting claims as to who used chemical weapons, the Assad regime, as the White House insists, or Syrian insurgents, as the Kremlin suggests. All of the evidence, including the findings of the recent UN inspection mission, would be weighed by the Security Council.

Even if the evidence points conclusively to Assad, a compelling nonmilitary approach remains, if it is backed by the United States, Russia—whose leading political and logistical role is essential—and the UN. Assad should be given a limited period of time to place all of his chemical production facilities and stockpiles under joint UN-Russian control. Moscow and UN specialists—both of whom have ample knowledge and experience in this regard—would then begin the long, complicated process of destroying those installations and weapons, whether onsite or outside Syria, as has been done in other countries. In addition, Assad would sign the 1993 international treaty that bans the production and use of such weapons and requires their destruction.

Influential segments of the US political-media establishment will vehemently object to any central role for Russia. For years, they have demonized Putin rather than analyze what he actually says about international developments. But given his longstanding argument that aggressive American policies have been fostering dangerous instability and jihadism in the Middle East, not democracy, there have been good reasons all along to think Putin would be receptive to this kind of diplomatic approach to the Syrian crisis. After the September 9 proposal made by his foreign minister, there can hardly be any doubt. (If nothing else, Putin’s insistence on a peaceful resolution should be tested.)

Certainly, the advantages of US-Russian cooperation would be enormous, possibly a turning point in international relations. The United States would avoid a military action that is likely to kill many more innocent Syrians without eliminating Assad’s chemical weapons capacity; again inflame Muslim and Arab opinion against America; undercut recently empowered moderates in Iran; do nothing to end Syria’s civil war, possibly making a negotiated settlement even less likely; create yet another US precedent of unsanctioned wars for others to imitate; and further the perilous drift toward renewed cold war between Washington and Moscow. Instead, their joint diplomatic effort at the UN could restore the necessity and legitimacy of the Security Council, revive the US-Russian plan for a Geneva peace conference on Syria, repair the needlessly damaged relationship between Obama and Putin and lead to fuller cooperation in the fight against international terrorism and in other dangerous conflicts that lie ahead.

This opportunity for a nonmilitary resolution of the crisis must not be lost. It is a major test for both American and Russian leaders, especially President Obama, who once called for a “new era of American diplomacy” but has yet to act on that promise.