Masha Kissel is a Lecturer in the English Department at the University of Dayton.

Today’s post is the a pedagogical field note, a category for discussing issues related to the Russian classroom.

This year marks the 125th anniversary of Mikhail Bulgakov’s birth. Moscow is celebrating with more than 100 events throughout the year, including a Bulgakov festival at Patriarch’s Ponds and an exhibition titled “Manuscripts Don’t Burn” at one of Bulgakov’s former apartments on Bolshaya Pirogovskaia. As if that wasn’t enough cause for celebration, the author’s most famous work, The Master and Margarita, marks 50 years since its first appearance in print. Penguin/Random House published a 50th anniversary Pevear/Volokohnsky translation of the novel, attesting to the work’s magnetic pull for an English-language readership.

"Follow me, reader!"

The Master and Margarita has followed me around for most of my life, and I can’t seem to shake it. If I had to choose a book to bring on a desert island, I wouldn’t choose this one. It’s not even in my list of top ten favorites. Yet, somehow, it became the focus of my scholarship and is a fundamental part of my teaching today, even though I no longer teach in a Russian Literature Department. I believe that the attraction of this work for me personally, and for my English composition students, lies in an unintended effect, a conflation of magic and history that creates a sense of enchantment with the Soviet past. Given the fact that the work satirically rallied against the clichés of Communist culture and was unpublishable during the author’s lifetime, it is a great irony that to today’s Western reader it seems emblematically Soviet.

In her article titled “Communism as Kitsch: Soviet Symbols in a Post-Soviet Society” Theresa Sabonis-Chafee writes about Russian nostalgia for Soviet totalitarian language and imagery.[1] It may seem that The Master and Margarita should be regarded as the opposite of Communist kitsch: Bulgakov’s status as outcast places him outside of Soviet cultural production and the work’s complexity continues to generate scholarly debate. Yet the novel’s characters and famous aphorisms (“second-rate freshness”) have become cultural symbols of the Soviet past. They are semantically ossified commodities, like Soviet pioneer pins. There are walking tours through locations mentioned in the novel, Master and Margarita merchandise and eating establishments around the world that have co-opted the characters in their brand.

I have spent much of my professional life thinking about the novel’s dual status as popular entertainment and as a timeless classic. The novel has always evoked a kind of Pavlovian nostalgia for my own Soviet childhood. I remember the forbidden thrill I felt as a Soviet tween, reading a work that made fun of the Soviet Union and very nearly depicted sex. When I re-read the novel as an Americanized college student, it awakened an acute sense of longing for a cultural sensibility I erased with years of diligent assimilation. Although the work no longer seemed edgy, it was a familiar memento, like looking at a photograph of myself in a Soviet school uniform. Today, when I have come untethered from my disciplinary mothership, the novel has unexpectedly become central to my identity as an instructor of composition.

The Duel Between the Professor and the Poet

After receiving my PhD in Slavic and holding several visiting positions, I followed my husband to a university that didn’t have a Russian program. I didn’t think that I would teach Russian literature again. My first teaching assignment at the University of Dayton as an itinerant Slavist was a second-year writing course, with unlimited freedom to pick a theme and corresponding texts. I did not initially choose to teach The Master and Margarita. One of the biggest challenges of creating a composition course is finding a balance between skill-building and content. A composition instructor must explain rhetorical strategies and concepts, illustrate differences in writing genres and conventions across disciplines, teach students how to engage in scholarly dialogue, and facilitate every step of the writing process for several types of assignments. Of course, good writing also requires intellectual and emotional engagement with a text. Choosing appropriate course material for this audience is the hardest part.

The majority of my writing students are in the business school or STEM fields. My course is their last required English class, and many enter it with a genuine dislike of reading and writing. They may never read another work of fiction, so my task is ideological too: I want to convince them of the value of literature.

The decision to use The Master and Margarita was a gamble. I was nervous that the work would be too strange for my students or that it wouldn’t work in a composition course. I chose it because I knew that I could teach it well and I hoped that Bulgakov could enchant and edify my students. Rather than wax poetic or drone practical about the worth of literature, I wanted to show them a world where a book could send you to prison and the pleasure of reading could feel like love. My course, titled “The Devil in Russia: Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita in Context” has been my greatest teaching challenge and possibly my greatest teaching success.

In a sense, I have been preparing to teach rhetoric in a Soviet context since graduate school. Part of my dissertation examined how Bulgakov’s early satirical writings for a newly literate Soviet reader influenced the form and themes of The Master and Margarita. This novel works well for thinking about how and why texts are made. For instance, a close reading of the conversation between Berlioz, Ivan and Woland in Chapter 1: “Never Talk to Strangers” helps students understand the role of audience in a rhetorical situation. I ask them to consider what characters choose to say and not to say in response to real and imagined audiences. The linguistic registers of the Moscow and Jerusalem plots allow the students to see how word choice and tone can give the reader a sense of the author’s intended readership. The Master and Ivan provide opportunity to discuss how purpose can influence an author’s choice of genre.

Teaching the novel in this unexpected setting has been hugely rewarding. We spend eight weeks on it, a luxury I never had before. Overwhelmingly, students fall in love with the work, but their affection progresses slowly. Most know very little about Russian culture and they are initially bewildered. We spend several class periods immersing ourselves in the first chapter to get over the culture shock. After we establish how names work and go around the class saying our patronymics, we focus on the material details of early Soviet Moscow, discussing fortochkas, primuses, communal apartments and pickled mushrooms.

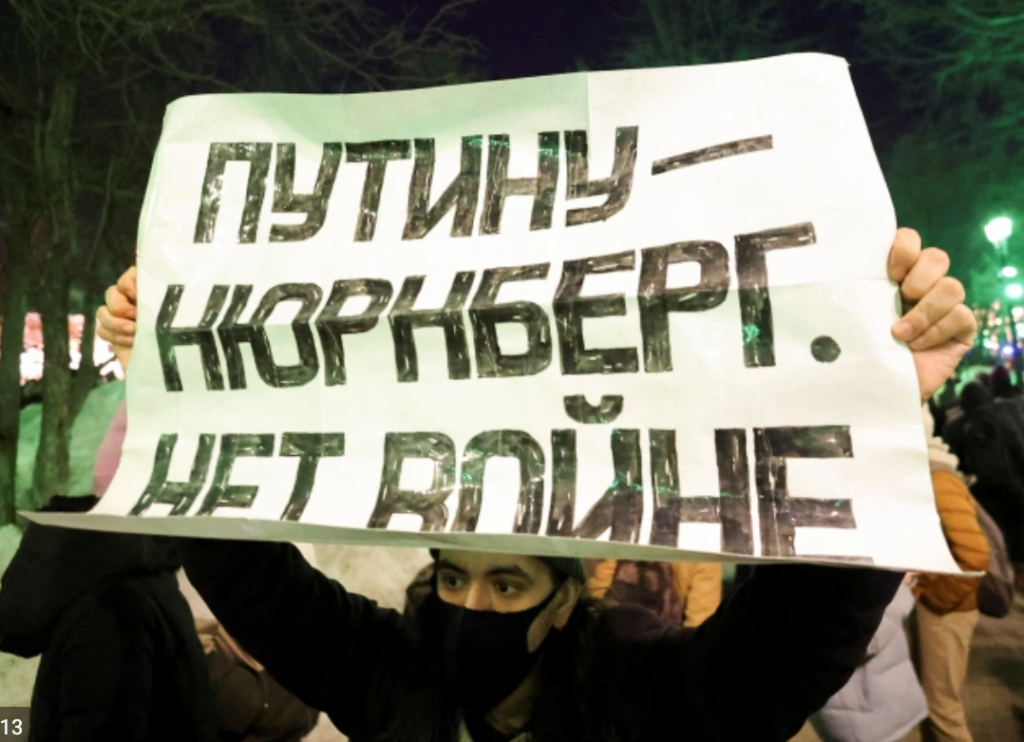

From a Western perspective, the novel perpetuates cold-war type narratives of Soviet Russia as a miserable and frightening place, of Soviet citizens mechanically going about their day in a monochrome urban hellscape, about the Russian temperament, bubbling with atomic intensity beneath a stoic surface. Darkly romantic portrayals of Russia on popular television shows such as FX’s The Americans and Netflix’s House of Cards have prompted discussions about the novel’s relevance to other periods of Soviet and Russian history.

Schizophrenia, as Predicted

While students eagerly engage with the novel’s Soviet past, I have noticed discomfort with the fictionalized rewriting of the Gospels. I teach at a private Catholic University where religion and faith are frequent topics of discussion and debate. I was aware that The Master and Margarita paints an unorthodox portrait of Jesus, but always saw Yeshua as a highly amiable character. Although some students find this humanized figure relatable, others describe him as “a coward” and “a manipulative charlatan,” who tries to escape death through cheap parlor tricks and by groveling before political authority (in reference to Yeshua’s conversation with Pilate, in which he seems to read his mind and cures his headache). They bristle at “his lack of confidence” and that he “doesn’t stand up for himself.” The true Son of God, they insist, is not afraid of anything and boldly accepts death. They are also dismayed that he is without family and does not have a lot of followers.

Interestingly, this response is not all that different from the Russian Orthodox Church’s critique of Bulgakov’s take on Jesus. In 2004, the making of Bortko’s serialized adaptation of the novel, prompted a strong reaction from the Church. Father Mikhail Dudko, a senior church official reacted similarly to Yeshua: “the real figure of Christ has been substituted by some helpless philosopher.” I have been impressed, however, that my students’ initial reaction inspires intellectual curiosity and has prompted some truly insightful research papers on Bulgakov’s theological and literary sources for the creation of Yeshua and Woland, as well as classroom discussions about how the Moscow and Jerusalem plots intersect and enrich the reading of each reality.

Enter the Hero

I have also been surprised by how many students similarly dislike the Master for his lack of manliness. They see him as weak and whiny and wish that he would “man up.” A female student who hadn’t said anything all semester stood up on the last day of class and spoke passionately for ten minutes about how upset she was that the Master was a loser who doesn’t really love Margarita. The novel has prompted conversation of censorship today by international students from China and Saudi Arabia. I was amazed to hear several typically quiet students speak out openly about censorship in their home countries and friends who have served time in prison for mocking the government or for selling illegal books.

Just as the novel vacillates between a serious tone and irreverent light-heartedness, so do our class discussions. There have been some good jokes (one student cleverly dubbed the novel a Mean Girls’ “Burn Book”), revelations in rock n’ roll history (did you know that Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil” was inspired by the novel?) and a critique of gender roles I hadn’t previously considered (a textually-supported comparison between Margarita and Pilate’s dog).

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of teaching The Master and Margarita for me has been my own enjoyment of it after avoiding it for several years. Although I rely on its Communist kitsch veneer to initially grab the students’ interest, in the course of teaching it in a new disciplinary and institutional context I have been reminded that this book really is unique and mysterious and houses unlimited possibilities for new readings and new connections to popular culture.

Note

[1] Theresa Sabonis-Chafee. “Communism as Kitsch: Soviet Symbols in a Post-Soviet Society.” Consuming Russia: Popular Culture, Sex and Society Since Gorbachev, ed. Adele Marie Barker (Durham and London: Duke University, Press, 1999).