Oleksa Drachewych is an Assistant Professor of History at Western University. He is the author of The Communist International, Anti-Imperialism and Racial Equality in British Dominions (Routledge, 2018) and the co-editor of Left Transnationalism: The Communist International and the National, Colonial and Racial Questions (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020). He is currently working on a book highlighting connections and parallels among Soviet atrocities during and after the Second World War with Russian atrocities in Ukraine today.

The post draws on his 2024 article in Russian History, “The Comintern and the National and Colonial Question: the Roots of Soviet Anti-Imperialism and Anti-Racism Reconsidered.”

Since Russia’s escalation in Ukraine, scholars have emphasized the nationalistic, militaristic, and imperialistic nature of Putinism. While engaging in its imperialistic war against Ukraine, in part motivated by its own nationalistic instrumentalization of the memory of the Second World War and of Russian and Soviet history, Russia is also focusing on growing its relationships with the Global South. Drawing on the legacy of Western imperialism and its impact in the Americas, Asia, and Africa, while also instrumentalizing Soviet policies promoting anti-imperialism or decolonization, Russia hopes that these nations will naturally align with them in world affairs and counter American unipolarity.

Of course, the reality is much more complicated. Many nations in the Americas, Africa, and Asia, even if they require Russian economic or political support for their own stability or development, have also shown their willingness to use the United Nations and other fora to criticize Russian actions. Nonetheless, Russia’s instrumentalization of Soviet history toward these regions has become increasingly apparent, meaning historians can play a role in challenging these narratives.

Many scholars and journalists highlight the Cold War as the main time period on which Russian leaders draw—whether it be Nikita Khrushchev’s support for decolonization through the United Nations, Soviet support for Cuba against American interference, or Soviet support for anti-apartheid efforts, to name just three examples.

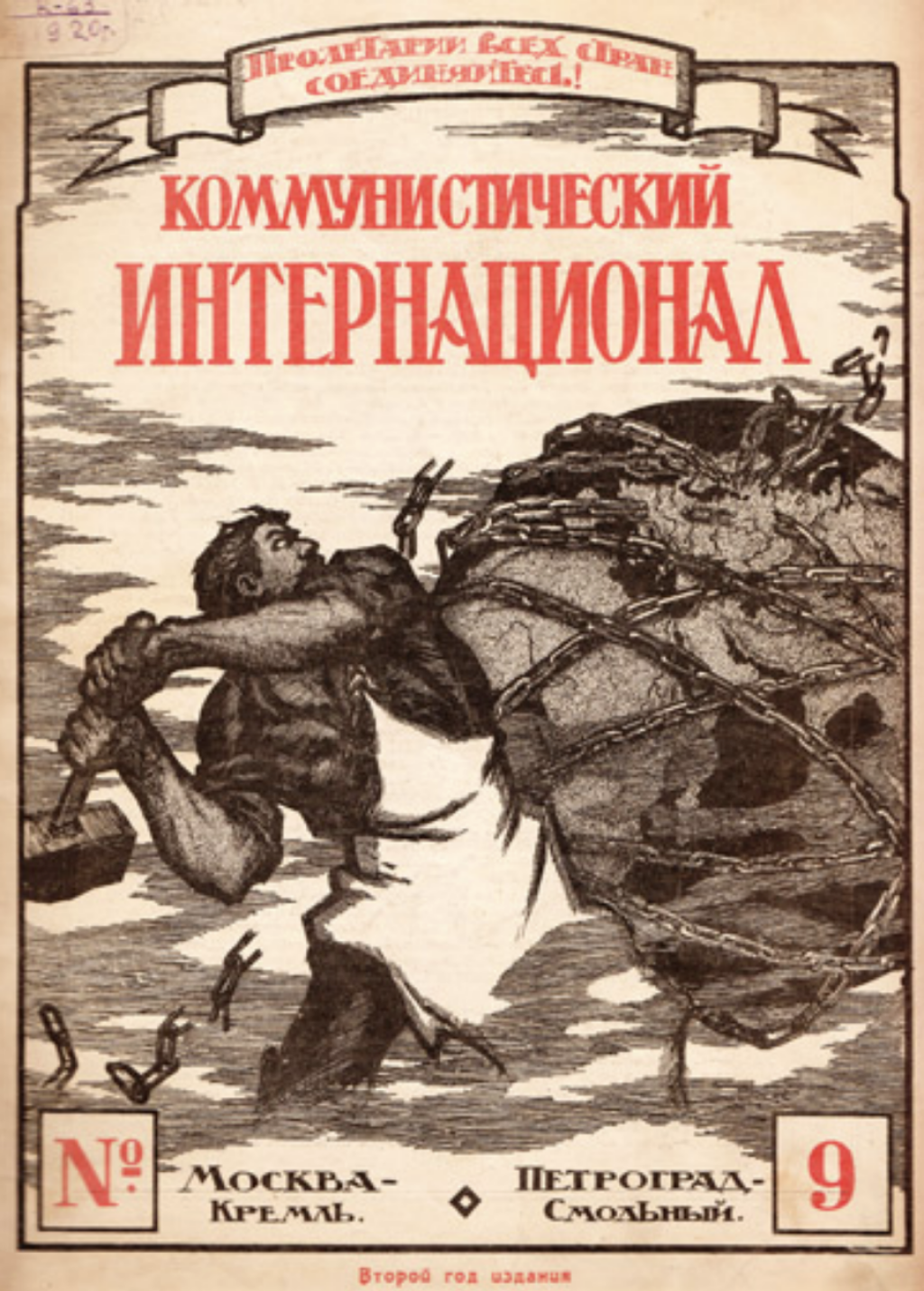

Russia’s history of instrumentalizing relations with the Global South should also include the Comintern. Through the Comintern, the communist movement developed many foundational principles of what would become Soviet anti-imperialism and anti-racism. Internationalizing Lenin’s ideas on self-determination and imperialism, the Comintern would also promote Soviet policies of korenizatsiia (indigenization) as having “solved” the national question. Black communists from the United States and Africa attended meetings or obtained training, while also introducing communists to the importance of responding to racial oppression. It is possible that Soviet support for anti-apartheid or the introduction of leftist ideas into civil rights movements in the United States would not have taken place without the forum the Comintern offered.

Recent scholarship on the Comintern has expanded our knowledge of communism’s importance to anti-imperialism, decolonization, and racial equality movements in the interwar period. This research moves away from Cold War binaries, and increasingly focuses on the people in the movement and on transnational exchange. Yet the issue of empire remains tricky. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the broader field of Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies has started to reconsider the history of the Soviet Union as an empire, while some call for a further decolonizing of the field. Several academic journals have focused on this trend; ASEEES even made it the theme for their 2023 Annual Convention.

Histories of the Comintern often emphasize its legacy in anti-colonial and anti-racist circles. The Soviet Union was seen as an anti-imperial nation. Asian nationalists, for instance, considered it an anti-Western, or at the very least, an Eastern or Eurasian nation capable of supporting the broader fight against imperialism. The Bolshevik fight against the Entente during the Allied Intervention into the Russian Civil War seemed to confirm the Soviet Union’s bona fides in the fight against imperialism.

Yet there were limits. Lenin himself understood that Bolshevik efforts during the Russian Civil War, especially in the Caucasus, could be perceived as imperial actions. Asian nationalists, though they saw the Bolsheviks as partners in their own struggle, sometimes believed they maintained an “imperial mindset.” Communists in the movement took issue with the doctrinaire nature of Bolshevik leadership, especially under Stalin. They diverged from Moscow’s edicts, using the ideas of class oppression or organizational tactics for their own aims.

The Comintern was also plagued by its own priorities. Under Lenin, it emphasized attention to “the East”—a result of the revolution’s failure to through Europe, but also because of the potential to form coalitions with oppressed peoples in the Global South. That “Eastern” attention, however, tended to ebb and flow, fluctuating with world affairs or Soviet priorities.

The League Against Imperialism, formed in 1927 with communist support, was a triumph for aligning communists with like-minded people, including prominent national leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru. By 1929, that support expired because of doctrinal shifts within the Comintern. In particular, communists could no longer align with non-communists, since the crisis of capitalism was believed to be at hand.

The Third Period in Comintern history, from 1928 to 1935, was defined by this approach and saw increased attention to fighting for Black liberation. Yet this same era also saw the Executive Committee turning Western European parties away from colonial matters in favor of domestic ones, eventually prioritizing the fight against Nazism. This shift led to the Comintern downplaying British or French imperialism during the Soviet search for allies. Meanwhile, racism remained a problem within the ranks of the movement.

The Soviet government’s efforts with respect to its own territorial periphery also had notable impacts. For example, in Australia, the local communist party’s “New Deal for Aborigines,” whose framers regarded it as the solution to longstanding Australian settler-Indigenous problems, was influenced by Soviet policies in Central Asia.

Most scholars of the Soviet Union argue that even if the Bolsheviks meant well, they often operated imperially. Other critics are firmer: the Soviet Union was an empire. Some in the Global South would agree—for example, the Soviet Union was not allowed to attend the Bandung Conference of 1955. Delegates discussed Soviet imperialism in reference to the USSR’s recent takeover in Eastern Europe, as well as Soviet policies in Central Asia.

As I concluded in my article in Russian History:

The Soviet Union, and the Comintern, promoted anti-imperialism, colonial liberation, self-determination of nations, and racial equality. Yet the Soviet Union was still an imperial power with its own misconceptions about race and ethnicity. Both of these statements can be true at the same time. This is the paradox of Soviet anti-imperialism and Soviet anti-racism.

This paradox must be considered in future studies of the Comintern and its platforms on anti-imperialism and racial equality. To do so would not be to return to Cold War paradigms, but instead to recognize the realities of Soviet policy, while allowing scholars to better highlight the roles of individual communists or the movement’s broader impact on world affairs—both positive and negative—without essentializing them. The Comintern must also be reinserted into histories of the Soviet Union and Empire as its ideological partner in promoting Soviet policies abroad. Such a nuanced study of the Comintern would enable the REEES field to combat Putin’s instrumentalization of the Cold War history of Soviet “anti-imperialism.”