Riccardo Nicolosi is Professor and Chair of Slavic Philology at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich.

This post is based on an article published in Ab Imperio in Spring 2022.

Present-day Russian political discourse is built on repeated references to phantasms of loss, constantly alluding to humiliation and offense and giving voice to fantasies of hate and retribution. In his speeches, Putin speaks of “parts of Russia’s own historical regions having been severed and detached” (speech of February 21, 2022), of how, after the declaration of Ukrainian independence, Russia felt “not only as if something had been stolen from it, but as if an outright robbery had taken place” (speech of March 18, 2014).

This rhetoric of privation feeds on and amplifies the real experience of loss and despair that Russian society went through after the end of the Soviet Union. In this framing, Russia’s recent history is an uninterrupted sequence of humiliations. These are the emotional drivers for imagining a future geared toward rectifying the losses suffered. The political discourse in today’s Russia is thus shaped by an intense emotional economy of resentment.

One of the most striking markers of Putin’s time is the cultivation of victim narratives. A society such as Russia’s—individualized, atomized, and depoliticized—is not held together by positively defined ideals, even though the constitutional reform of 2020 gave formal grounding to the identity-forming significance of tradition and conservative values. Instead, many Russians are united in a certain emotional reality—that of resentment. A shared sentiment of deep-seated grievance as a result of alleged humiliations draws those living in Russia together, creating, as a logical consequence, the desire for Russia to “rise from its knees.”

Since at least 2007—that is, since Putin’s widely publicized, confrontational appearance at the Munich Security Conference—the Russian president’s speeches have consistently presented the country as having suffered profound injustice, insults, and deceptions at the hands of “the collective West.” Per Putin, the conflict around Ukraine is the latest (for the moment) stage in the political agenda to “contain” Russia, which is being stubbornly pursued by Western powers.

In full conformity with the emotionally charged rhetoric of resentment, the sentimental space of seeking revenge created in this way has a substitute object that is, on the one hand, sufficiently concrete, and, on the other hand, not so tangible as to be annihilated by its own reality. In the current Russian political discourse, the “collective West,” which Putin also called “the empire of lies” in his speech of February 24, 2022, assumes the role of the agent that inflicted the humiliations and wounds the nation has lived through and the impact it feels as a result. This narrative makes the West the real target of Russia’s thirst for revenge, since Ukraine is presented as its puppet. The rules for ascribing particular states and institutions to the “collective West” are somewhat flexible, but the notion is concrete enough to allow for an approximate localization of “the enemy.”

Quite frequently, the source of the humiliation Russia has putatively suffered is made even more abstract and de-historicized through allusions to so-called Russophobia—that is, anti-Russian sentiment. For approximately the past twenty years, any criticism of Russia is interpreted as a manifestation of a deeply rooted, global hatred of Russian culture and the Russian people. The reasons for the existence of this supposedly universal and centuries-old pathological state are explained only vaguely through references to a collective envy of Russia’s size, and hence its geopolitical power, which supposedly transforms this envy into fear and hatred. The idea of anti-Russian sentiment embodies a paranoid-victim narrative that cannot be falsified and so, like all paranoid narratives, serves to “explain” a wide range of phenomena. “The world is against Russia, because Russia is Russia”—such is the paranoid, tautological foundation of the narrative of anti-Russian sentiments as part of the current discourse of resentment.

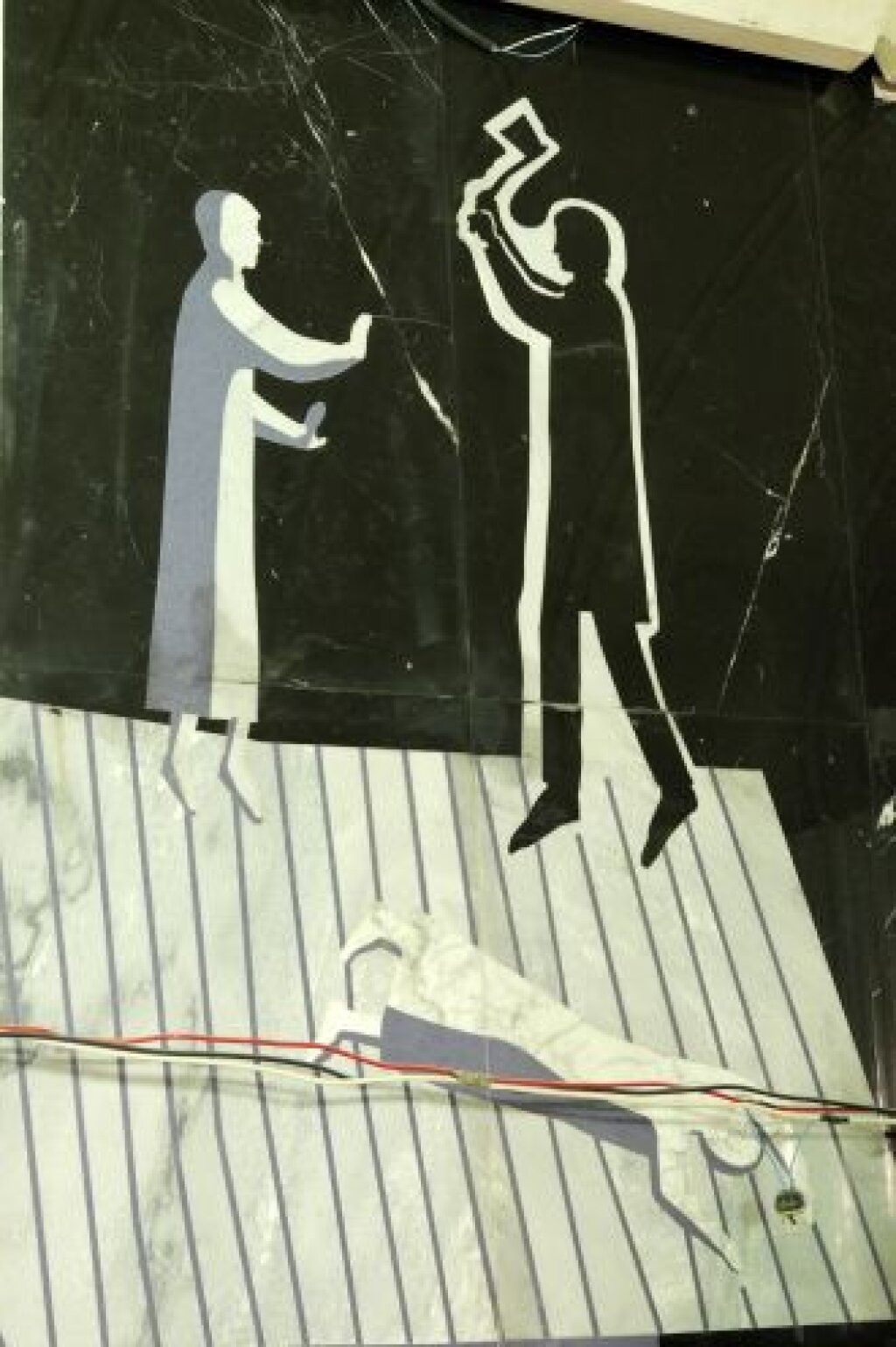

Putin transformed the exhibition and even cultivation of Russia’s own past impotence and its intensifying frustration into rhetorical and military aggression. The aggressiveness of Russian political discourse, which the Kremlin has promoted and vividly illustrated all these years, also comes across in a dramatic appeal to fears of the country’s supposedly imminent fragmentation and partition, which the West apparently craves. Following the Russian line of reasoning, Ukraine’s “breaking away” is only the first stage in a plan will culminate in Russia’s division and transformation into separate, independent states. The loss of Ukraine becomes synonymous with a mutilation of the Russian body politic, and with it, the “Russian soul.”

Russian propaganda points again and again to the purported existence of Western plans for a partitioning of Russia. Fanciful maps are presented featuring states like “Moscovia,” “Siberia,” “Ural,” “Tatarstan,” and so forth. Putin’s argumentation frequently includes horror scenarios of Russia’s fragmentation. One example was a controversial (or staged as such) conversation at the Council for Human Rights in December 2021 with the film director Aleksandr Sokurov, who pleaded for a separation of the republics of the Northern Caucasus from the Russian Federation. Putin replied in a furious, hysterical tone, saying that Russia’s territorial integrity must never be questioned—unless one wants Russia to disappear as a state or, in the best case, shrink to what, in the Middle Ages, was the Grand Duchy of Moscow.

In this context, the war in Ukraine, in which the Russian Federation is violently slicing off parts of a neighboring country, becomes a brutal reaction to state-generated fears of Russia’s complete disintegration as a state. In Ukraine, Russia is realizing the very horror scenarios it had habitually ascribed to its hypothetical existential adversaries: invasion and occupation, forced assimilation and colonization by foreign powers, territorial division and fragmentation, terror and extermination.

Ukraine becomes what Russia—according to this line of state propaganda—could have become. It also becomes a projection of Russia’s own anxieties regarding internal, as well as external, “enemies.” The war of extermination Russia now wages against Ukraine “shows” what devastating consequences can follow a regime change resulting from street protests. A Russian “Maidan,” the absolute worst nightmare for Putin’s regime, must be prevented at all costs.