Elżbieta Olzacka is Assistant Professor in the Center for Comparative Studies of Civilizations at Jagiellonian University working on cultural mobilization and the dynamics of national identity construction in Ukraine during the Russian invasion.

The article on which this post is based, “The Development of National Cinema in Post-Maidan Ukraine,” appeared in the July 2022 issue of East European Politics and Societies.

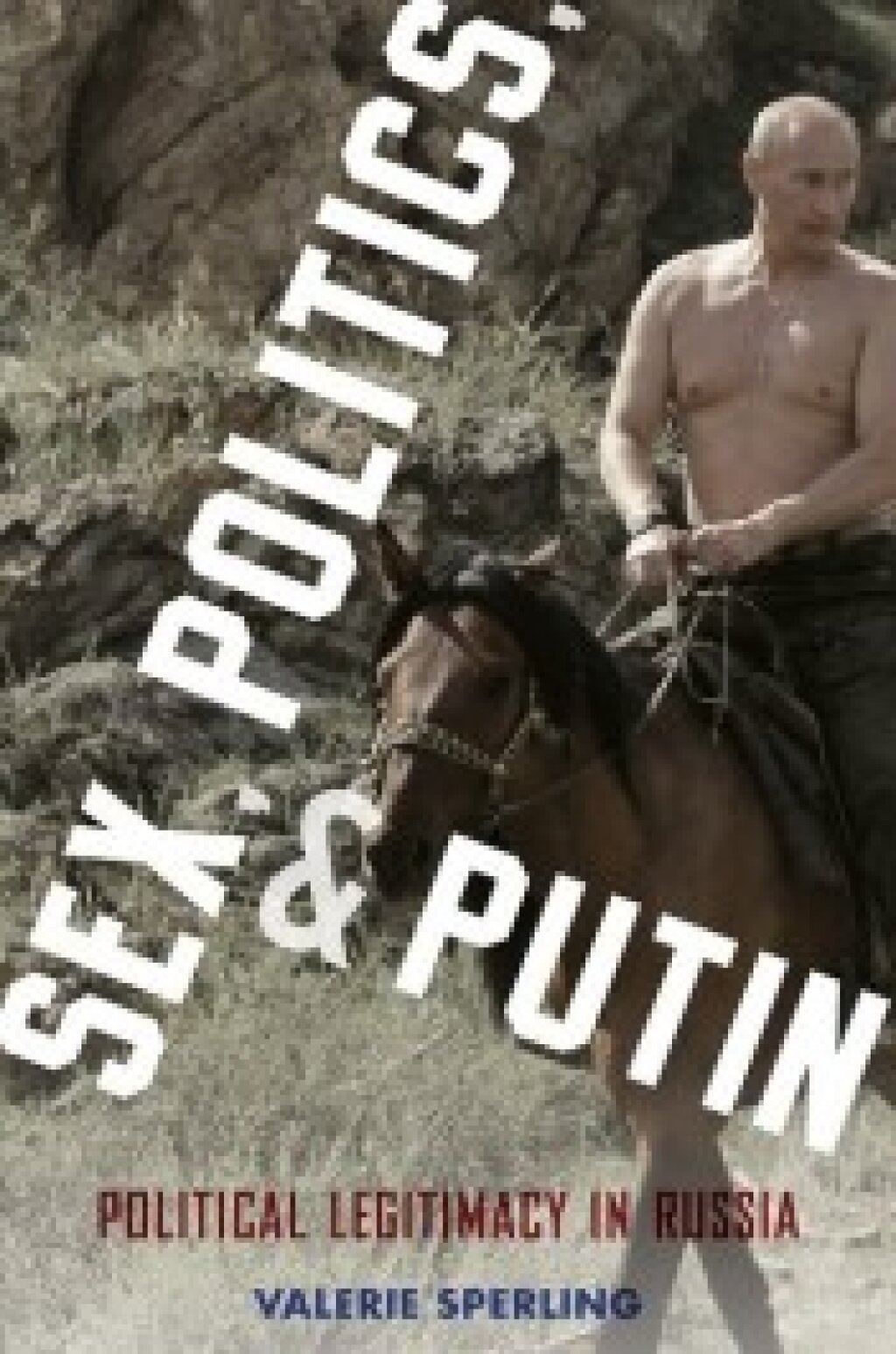

Above: Ukrainian film producers onstage during the 2022 European Film Awards. Source

In the wake of the Revolution of Dignity in 2013–2014, Ukraine experienced a remarkable cultural renaissance. The film industry likewise felt a surge of innovation. Suddenly, Ukrainian filmmakers felt new wind in their sails after years of constant hardship. This creative fervor was fueled by significant state support for cinema at levels unprecedented in independent Ukraine. The Ukrainian State Film Agency (Derzhkino for short) was restructured. New, more democratic standards replaced the old film financing system, which relied heavily on bribery and personal connections.

Funding for Dzerzhkino has grown significantly. The budget for 2022, before the full-scale Russian invasion, was planned to be UAH 1.6 billion, compared to UAH 63 million in 2014. The outcome was a significant increase in the number of Ukrainian films being made. Finally, efforts to promote and distribute Ukrainian productions in domestic and global markets have led to Ukrainian films being screened in theaters, distributed via international streaming platforms, and recognized at festivals worldwide.

The development of new film awards demonstrates domestic cinema’s rising prestige. While presenting the newly founded Kinokolo award in 2014, Serhiǐ Trymbach, head of the National Filmmakers’ Union of Ukraine, disarmingly claimed that had previously been no need to grant an annual award for the greatest Ukrainian film because there were simply too few films. Ukraine also has its own Oscar equivalent, the Golden Dzyga Film Award (Zolota dzyga), presented annually since 2017 by the Ukrainian Film Academy.

At the same time, post-Maidan cinema is made in a country at war, with strong support from a government pursuing a military agenda. Russia annexed Crimea in March 2014 and has since backed pro-Russian separatists in the country’s east and south. The so-called “anti-terrorist operation” in the Donbas swiftly morphed into more traditional warfare.

The war affected both the subjects filmmakers chose to tackle, and the film policy pursued by the state. Derzhkino’s head in 2014–2019, Pylyp Illienko, did not try to hide the political motivations behind the government’s decision to raise funds for the growing Ukrainian cinema. “The film industry is even more effective than guns because it’s fighting for the mind,” he said.

In the conditions of the hybrid war Russia has waged against Ukraine since 2014, “tele-decolonization” has risen to the top of the agenda for Ukrainian authorities. The aim is to limit the impact of Russian propaganda promoting Russia’s version of events in Ukraine and to prevent Ukrainians from viewing themselves through Russian eyes.

Bolstering these efforts were actions by activist groups like Vidsich, which in 2014 called for a boycott of Russian television and movies. Many theaters in Ukraine joined the boycott and stopped showing Russian films. State regulations followed the actions of the activists. Already in October 2014, Derzhkino published its first list of banned films. These movies either featured actors who openly supported Vladimir Putin’s policies or who promoted the power structures of the “aggressor state.” A law that seeks to shield Ukrainian public spaces from “hostile content” went into effect a few months later. All Russian films made after 2013 were included, not just the ones listed above.

The (re)construction of “national cinema” became the second focus of post-Maidan film policy in Ukraine. Derzhkino headPylyp Illienko took this assignment very seriously. As an activist in Euromaidan and a politician affiliated with the nationalist “Svoboda” party, he felt duty-bound to make Ukrainian cinema more Ukrainian. The March 2017 implementation of the law “On State Support for Cinema in Ukraine” provided the legal framework necessary to make these ambitions a reality.

The new legislation precisely delineates the criteria determining what films count as “national” and are eligible to receive state support. Moreover, it clearly and concisely defines what constitutes a “national film.” Every film that applies for a state subsidy receives a “national film certificate” once the Council for State Support for Cinema has evaluated it. Ukrainian or Crimean Tatar must account for 90% of all dialogue, and the film must have been produced on Ukrainian territory with the cooperation of Ukrainian filmmakers and actors.

In practice, therefore, films made in the Russian language were excluded from the category of “national cinema,” causing significa controversy among filmmakers. Most vocal in their opposition were creators whose first language is Russian, like director Sergei Loznitsa, who called the idea of dubbing his 2018 film Donbas in Ukrainian “strange.” First, he notes that, in the area where the action takes place, people speak Russian, meaning dubbing in Ukrainian would sound unnatural. Second, in his opinion, such a change would be unnecessary because “everyone understands Russian well,” the language being “absolutely clear and accessible to all who live here.”

However, many people responsible for shaping cultural policy in Ukraine now consider this argument irrelevant. They think cinema is a fundamental tool for systematically promoting Ukrainian language and culture. In fact, the new law’s introduction highlighted the shortcomings of Ukrainian film studios, which struggled to provide Ukrainian soundtracks and dubbing or to find actors with sufficient proficiency in Ukrainian.

Some in the film industry also voiced concerns about the growing role of the state in the arts. Illienko made it clear in an interview with “Ukraïns′ka Pravda” that the Derzhkino he managed was eager to fund movies to help Ukrainians develop national pride and a modern identity. Thematic competitions were used to promote films about the Ukrainian national liberation movement of the twentieth century and about the contemporary Russian invasion. In 2018, a special Ministry of Culture program funding “patriotic films” with a budget equal to Derzhkino’s total budget further fanned the flames.

Despite these controversies, recent Ukrainian films are worth a look. The new Ukrainian cinema is simultaneously establishing a new cultural milieu in Ukraine and making significant inroads into the European cinematic landscape.