Alsu Tagirova is a Faculty Member in the Academy of History and Documentation of Socialism at East China Normal University, Shanghai.

The history of the Sino-Soviet border is often considered a stumbling block in the relationship between two powerful states. Most academic works examine it as such and pay a significant amount of attention to this history’s power dynamics. While this approach reflects history prior to the 1980s, starting from the Gorbachev era, the issue was subjected to internal conflict within the Soviet Union. With ethnic tensions on the rise and union republics seeking independence, Moscow found itself searching for solutions to thorny problems within Sino-Soviet border relations. The aim was to locate a scenario that would not only satisfy Moscow and Beijing, but would also be acceptable to the administrations in the regions.

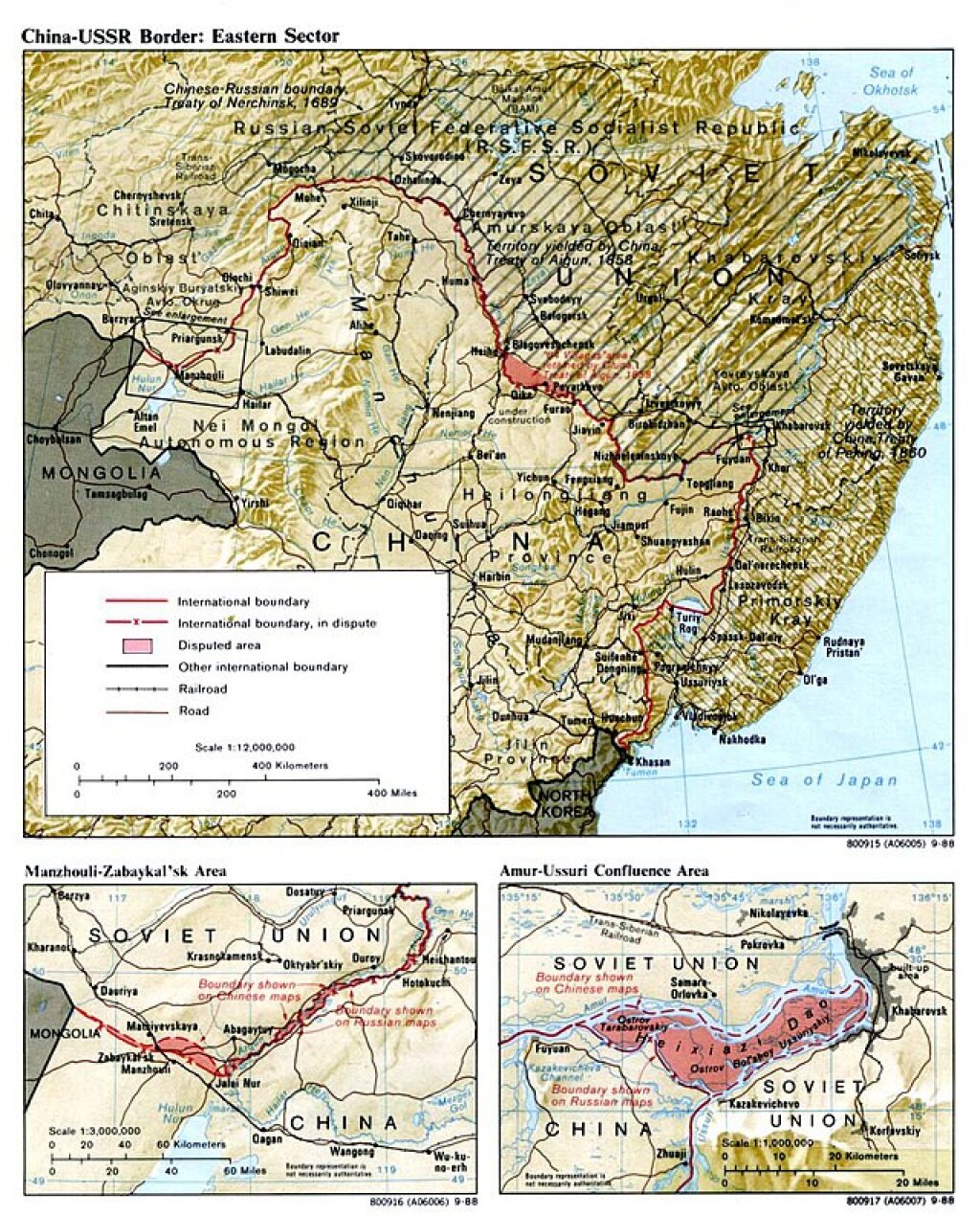

The bilateral border first became problematic in the early 1960s, as Sino-Soviet relations began to deteriorate. The negotiation that ensued can be roughly divided into three distinct periods. The first round, in 1964, ended in preliminary agreements, which were never signed because of the Sino-Soviet split. The second round of talks, which took place between 1969 and1978, was a direct result of the Damanskii (Zhen Bao) Island Incident. The talks revolved around the actual border issue for only the first three years, whereas the two delegations spent the remaining six discussing issues related to ideology and the state of Sino-Soviet relations. After almost a decade of negotiations, the parties failed to reach a final resolution. With the beginning of Mikhail Gorbachev’s reforms, China and the USSR were able to initiate a rapprochement and hold border talks between 1987 and1991. This round concluded with the signing of the Sino-Soviet Agreement, which stipulated mutually agreeable conditions relating to the border’s eastern part. Meanwhile, two contentious sections, also located on the border’s eastern part, were set aside for later discussion.

The Soviet government first invited representatives of Central Asian republics to the negotiation table in 1988. The Chinese were reportedly worried that the local population would not accept a Sino-Soviet border agreement unless they were granted some agency on the matter. One Soviet diplomat recalls that “the leadership of these republics, as members of the highest political governing bodies of the country, was aware of the content of the directives that the Soviet delegation had received [from Moscow].” However, the local governments could hardly play a significant role in the formation of Soviet directives in the 1987- 1991 negotiations.

On 16 February 1989, after his return to Moscow, Georgian leader Eduard Shevardnadze reported to a Politburo meeting that the Chinese hoped to secure Soviet territorial concessions in the Khabarovsk region in exchange for 27,000 km2 in the Pamirs. Shevardnadze advised the Soviet leadership to accept the offer. At the time, the Soviet leadership was battling the rise of ethnic conflicts across the Soviet republics and, presumably based on these considerations, refused the proposed territorial swap.

In February 1991, on the initiative of Ilya Rogachev, then head of the Soviet delegation, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the USSR organized internal consultations with representatives of the Soviet republics bordering China. As a result of related meetings, representatives of the Russian, Kazakh, Kirghiz, and Tajik Soviet Socialist Republics became members of the Soviet delegation.

In June 1991, members of the central government, headed by G. V. Kireev, visited Dushanbe, Alma-Ata, and Bishkek: in these cities, they met with leaders of the Central Asian republics and representatives of republican municipalities bordering China. The leaders of Union republics agreed in principle with Soviet directives for border negotiations. However, they expressed a desire to participate directly in talks with China and shared some of their specific concerns. Instead, the Soviet governmental delegation agreed to take into account reports produced by the special commissions established in the union republics, but not include the republics’ representatives directly.

After the fall of the USSR, Russia, as the successor state, received all rights and obligations put forward by the treaties to which the USSR was a party. Meanwhile, the Central Asian republics, as autonomous successor states, could choose whether to remain a party to any given treaty. Hence, prior Soviet obligations on the Sino-Soviet border issue were legally binding for Russia, but not Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, or Kazakhstan. Reportedly, the Chinese side wanted to negotiate with each of the former Soviet republics separately, only agreeing to speak to a Joint Delegation after lengthy talks.

By 1991, Soviet and Chinese diplomats had already initialed partial agreements on the delimitation of the western (Central Asian) section of the Sino-Soviet border. The Joint Delegation was bound to conduct talks within the framework of the directives inherited from its Soviet predecessor, an approach that seemed to yield little result. On the one hand, all post-Soviet states experienced pressure from their domestic constituencies. On the other hand, the central governments in all of these states believed that the cost of “no agreement” with China on the border question would be so high that they chose to risk dealing with complex issues at home over passing up the opportunity to settle the border with their strongest neighbor. They ultimately chose to do so with little regard for domestic opposition or the restrictions imposed by the Soviet delegation’s earlier commitments.

In April 1998, the Kazakhstani delegation chose to bypass the entire construct of the Joint Delegation and negotiate with the Chinese directly. Tajikistan began similar consultations in October 1997. The Kyrgyz part of the Joint Delegation took on an independent position and engaged extensively in bilateral consultations with China. Russians, too, conducted most of their negotiations with China directly.

Originally intended as a demonstration of unity and a show of strength in a power play with China, the Joint Delegation became almost redundant as a negotiating body. The commitments the Soviet government had made before 1991 limited the range of positive outcomes so significantly that each republic decided to try renegotiating their positions one-on-one, although the format of Joint Delegation was never officially terminated.

In addition to border issues, the former Soviet republics also signed a series of agreements with China to ensure the stability of the former Sino-Soviet border through the implementation of confidence-building measures and mutual reduction of military forces in border areas. These agreements have also become the basis for the establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a regional body that originally included all participant states of the Sino-Soviet border talks and which continues to expand its membership to include other regional powers.