This is Part III of a three-part series. Part I may be found here and Part II here. A version of this piece appeared originally on Gorky Media.

Ilya Vinitsky is a Professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at Princeton University. His fields of expertise are Russian Romanticism and Realism, the history of emotions, and nineteenth- century intellectual and spiritual history.

Translated by Emily Wang, Assistant Professor in the Department of German and Russian Languages and Literatures at the University of Notre Dame.

Part III. The Don Quixote of Newspaper Fantasy

The Richest American Name

Ivan Ivanovich Narodny (real name — Jan Sibul, 1869-1953) arrived in America in February 1906 at the invitation of some young American journalists who sympathized with the Russian liberation movement. Onboard, he had presented himself as John Rockefeller (the name of the richest American then known to him).

In the declaration he submitted upon arrival, he lied in response to almost every question and was cheerfully accepted into his new homeland. In his first interviews with the American press at port, he declared himself a great Russian revolutionary, the head of the Kronstadt uprising, the creator of the Red People’s Guard and the Baltic Constitution. (He actually had been a delegate at the First Bolshevik Party Conference in Tammerfors, now Tampere, Finland, but his participation in revolutionary activities was minimal and, in general, controversial.)

He also related that he had been imprisoned in a one-room cell in Peter-and-Paul Fortress for four years on account of his revolutionary activity. There he “befriended” his only companions, a kind mouse and a loyal flea, which he painted red to distinguish it from the other fleas. In fact, Narodny—then still Sibul—had been not in prison, but under psychiatric observation in relation to his forgery of banknotes.

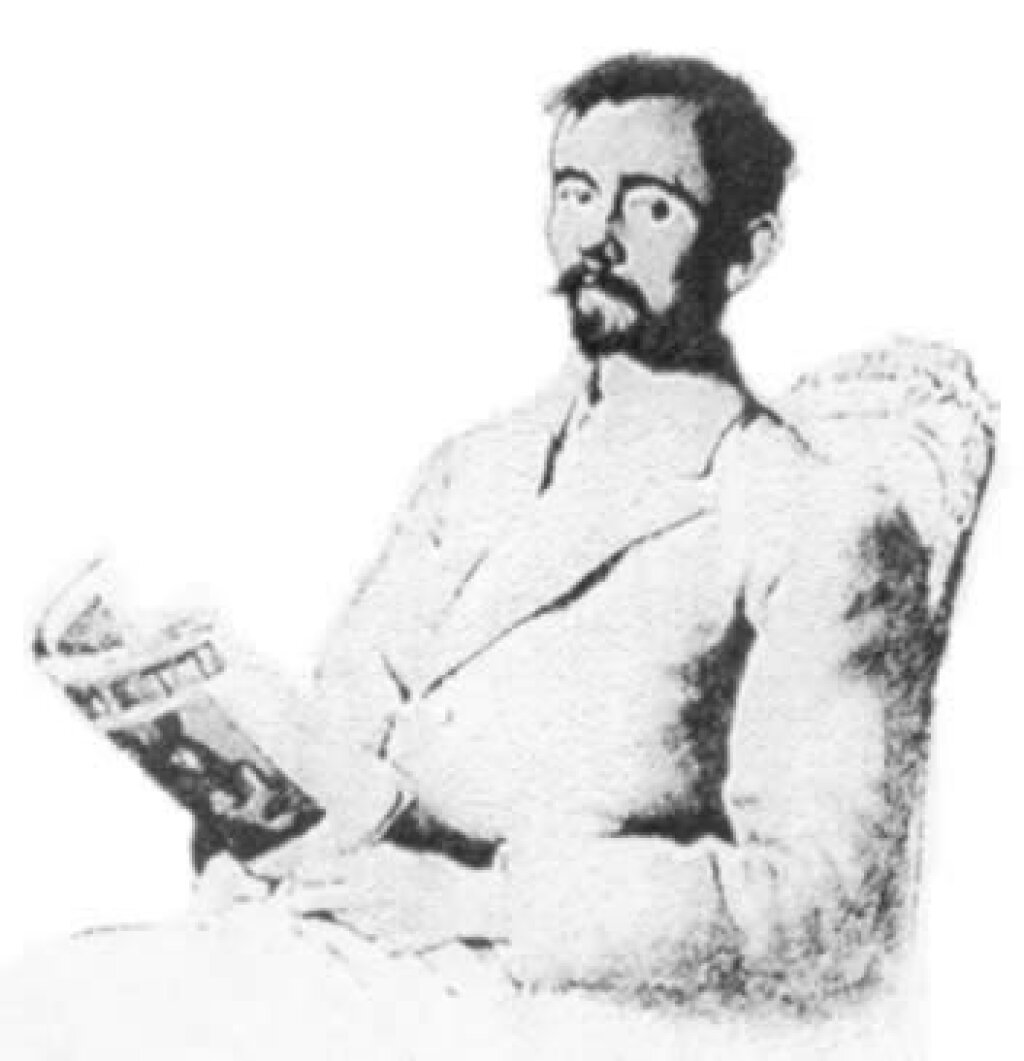

“Ivanovitch Narodny. A fine type of the professional Russian revolutionist” (reading Pushkin’s Boris Godunov)

In the end, he was released as partially insane, for it was noted that he considered himself an incarnation of the Buddha and believed that he desperately needed money to propagate his teachings and found an Estonian colony in Latin America. Narodny also told the American public that his wife and two sons were killed by Cossacks. In an interview that took place two days later, he related how his wife had lost her mind, while he had secretly gone to Russia to save his sister, who was being molested by imperial forces. (Interestingly, the woman in the photograph of the "sister" he saved looks exactly like his new wife, who accompanied him from Finland in place of Sibul's previous wife, whom he left behind.)

Ivan Ivanovich Narodny, announcing his overthrow of Emperor Nicholas II and the United States’ recognition of the new Russian Provisional Government.

In other interviews (given at the same time!) Narodny presented himself as a Russian aristocrat, a courtier, a close acquaintance of the Tsar, a general in the Russian army, and a knight of a high imperial order. He learned English very quickly and actively participated in revolutionary fundraising. He was even one of the organizers of Gorky’s visit to America. (There’s a photograph of Narodny sitting next to Gorky and Mark Twain.)

Ivan Narodny (is in the lower left corner) at the dinner for Maxim Gorky on April 11, 1906

Having realized that Gorky was a competitor who did not want to share the money raised for the revolution, Narodny began to spread malicious rumors about the Stormy Petrel of the Revolution (Gorky’s poetic nickname), which ended up cutting the revolutionary writer’s mission short. Then he made up an entire cycle of stories about a conspiracy against Gorky, organized by the founder of a Russian spy network in America. Tellingly, the attached photograph of this agent depicts... Narodny himself.

The Russian Jefferson

In 1908, the revolutionary Narodny “overthrew” Emperor Nicholas II in his own Declaration of Russian Independence. He announced the creation of the United States of Russia and swore fealty to this new republic. At the same time, he presented himself as an eminent critic of ballet and music. In 1916, he published his book Dance, in which he formulated a mystical conception of this art form.

This publication was accompanied by articles that had first been released in American music and ballet journals. These articles were dedicated to beautiful ballerinas, Duncan's rivals, innovative composers, and talented artists, among whom his own wife, a singer, particularly stands out. In his writings, Narodny included letters attesting to the fact that he had fabricated interviews with celebrities — for example, Anna Pavlova’s preface to one of his works, or excerpts from a letter that the Finnish composer Jan Sibelius had written him.

Narodny was also an active businessman, opening fake or semi-fake foundations and firms by presenting himself as an agent of the Russian Imperial government. During the First World War, he tried to “purchase” American submarines for Russia. After the Revolution, he claimed to have obtained the richest collection of Russian Imperial jewelry, as well as huge resources of Siberian furs and vodka.

Narodny actively participated in organizing music festivals and concerts in Woodstock, N.Y., working to seek out and promote new stars. One of the ballerinas he discovered and praised, Lada, surpassed (in his opinion) Isadora Duncan herself. She repaid her patron and worshipper a hundred times over. A Russian Grand Duke visiting America was so taken with her “Dance of Salomé” that, on her request, he procured amnesty for the former revolutionary Narodny.

From the beginning of the 1910s, Narodny was an employee of Hearst’s newspaper syndicate. He began publishing in the Sunday supplements — one apocryphal, sensationalist story after another. These articles covered a wide range of topics, though all were associated, as a rule, with Russia and Russian art. He did not accept the Bolshevik Revolution and even declared that he was preparing to do battle with it as the head of a new revolutionary government in Kronstadt. American newspapers reported that Narodny, “the dance master,” had departed for Russia in the role of its new leader. He never did.

The Village Guru

At the end of the 1910s, the theosophist Narodny (recall his earlier belief that he was a reincarnation of the Buddha) became the secretary and domestic guru of the aforementioned American millionaire, the modernist artist Bob Chanler, and lived in his famous “Fantasy House” in Greenwich Village – the center of New York bohemian life during the first half of the 1920s. Here, he became acquainted with wealthy people and aristocrats (including the Prince of Wales), arms dealers, spies, adventurers, and ladies from all levels of the demi-monde.

In the middle of the 1920s, Narodny stood at the head of a group of Russian émigré artists. This group included his friend David Burliuk, one of the founders of Russian futurism, who had painted Narodny’s portrait and dedicated a poem to him, as well as the sculptor Sergei Konenkov, who had built a wooden chapel at Narodny’s farm in Connecticut. He also published a modernist journal, funded by Chanler, in which he announced that he had created a new cosmocratic religion calling for the union of science and art and for the liberation of artists from the yokes of commerce and machines. He presented himself as the high priest of this new religion and, in addition, the founder of the science of time. He also advocated for Dionysian ritual dances (preferably performed while naked) and polygamy (he had two wives himself).

During this period, Narodny printed the erotic “mimodrama” (pantomime) dystopia The Skygirl and a series of mystifications that came to be widely disseminated not only in America, but throughout the entire Anglophone world. (Hearst’s newspapers with Narodny’s articles came out in Canada, Great Britain, Australia, and New Zealand, and some of them were translated into French, German, and Estonian.)

His specialty was the nonstop production of various mystifications. He wrote about Lev Tolstoy’s prophesy about World War One; a Russian spy network in New York; a “man in an iron mask” who had languished for almost half a century in Keksgolm (now Priozersk, Russia) near Lake Ladoga (in Narodny’s version, this was Peter III, the grandfather of Alexander I); the escape of the daughter of the last Russian emperor to San Francisco; the mysterious Shambala; Catherine the Great’s romance with American Admiral John Paul Jones, etc. Depending on the topic, he called himself either the author of the Russian Declaration of Independence, or the author of a foundational book about modern dance, or the founder of the occult art of chronosophy, or just a prominent poet, writer, literary scholar, philosopher, journalist, playwright, and by far the most informed American expert on Russian affairs, a close friend of Teddy and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Gorky, Lenin, Nicholas II, Tolstoy, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, David Burliuk, Nikolai Roerich, Reinhold Glière, Isadora Duncan, and Sergei Esenin.

The World of Ivan Narodny

Narodny’s remarkable propensity for newspaper fantasy came from his capacity for creating mystifications in “clusters” and series. One invention would lead to a second, then a third, a fourth, a fifth, a ninth, and so on. Though his favored motifs elaborated upon and contradicted one another, the author had no interest in correcting contradictions, as we saw on the example of his Esenin cycle.

All in all, his apocryphal texts most closely resemble cheap melodramas or musical librettos (he tried his pen at this genre as well). Moreover, Narodny managed to create a peculiar and colorful universe inhabited by European aristocrats, American millionaires, brave revolutionaries, extraordinary crooks, visionary artists, adventurous archeologists, Mongolian lamas, Northern composers, and even Martians. Naturally, Narodny himself stood at the center of this universe. He was the keeper of all the world’s rumors and secrets, a spiritual wanderer and madman, an impersonator and “playboy of the imagination,” the owner of the rarest treasures and artifacts, friend and confidante of all celebrities, a “tabloid modernist.” In this imaginary world, split into numerous (p)articles, anything was possible, even the most fairy-tale transformations and the freest associations of Narodny’s imagination, unhindered by any boundaries of healthy rationality.

In general, this journalist’s compulsive myth-creating expressed not only the eccentric cast of his own thoughts (and he really was diagnosed as "partially insane"), his material interests (he was always in need of fast cash), private aspirations (the utopia of syncretic universal art, promoted by high priests like Isadora), and idiosyncrasies (unbridled ambitions and desire to expand his own significance to global proportions). His story also exemplifies American “yellow” (tabloid) journalism in the age of Hearst, with all its craving for sensationalism, melodrama, and exotic, reckless mobility, colorful superficiality, political bias, absolute unscrupulousness, and the cynical exploitation of readers’ tastes and expectations that were far from refined. In a certain sense, Narodny’s newspaper articles might be likened to an Etruscan vase, in which the eclectic ashes of contemporary history are artificially mixed together.

David Burliuk, Portrait of Ivan Narodny and His Other Selves

Of what was this world of Ivan Narodny made? It is important to note that he did not invent his stories whole cloth, but rather transformed (sometimes to the point of unrecognizability) things he heard from acquaintances and facts or testimonies he found in the newspaper. Thus, Esenin’s imprisonment, in Narodny's version, proceeds from the news that the poet had stayed in a psychiatric hospital not long before his death, while the antique urn motif derives from the dances depicted on Etruscan vases in Duncan's possession.

The American dancer Dorothy Billings, whom Narodny sent to Esenin’s cell to comfort the poet and to whom he “dedicated” his verses written in blood, actually did exist. By contrast, the poet’s “authentic” farewell verses addressed to Duncan (“Invocation of Death”) were created by the fantasist to fill in an intriguing information gap, since the American press had first reported a suicide poem dedicated to Duncan discovered next to the couple's scattered correspondence and a torn-up photo of their young son. Narodny's fantasy was also an effort to “debunk” the poem “Farewell, my friend, farewell,” printed in newspapers in translation on December 31st, 1925, as poor work unworthy of Esenin. In the USSR, incidentally, this poem was first published on December 29th in the Red Gazette as part of the article “Esenin and his death.” Interestingly, some Esenin scholars moonlighting as conspiracy theorists fifty years hence have also subjected the poet’s farewell verses to doubt (granted, working with entirely different motives).

Picture of an Etruscan vase from Ivan Narodny’s article about the Russian “religion of dance,” discovered by his student ballerina Lada in Novodevichii Convent

As far as Esenin and Duncan themselves are concerned, the tabloid fantasist Narodny saw them, above all, as iconic images of bohemian culture and high priests of the “Roaring Twenties.” He “simply” completed and “beautified” their life stories according to his own preconceptions, the demands of the mass-market adventure genre, popular in the “yellow” press, and his own theosophical ideas about the future synthesis of poetry, dance, and life. The paradox here is the fact that this naïve “completion” allowed him to express and even take to its logical, yet absurd, conclusions the pretentious, sensational, journalistic, cosmopolitan, “operatic” and “tasteless” character of the tragic life and art of the real-life Serge and Isadora.

“The fairy tale,” remark the authors of one of the latest biographies of Esenin, “was the formula for Esenin’s life.” These words are no less relevant to the fate of Duncan. But in both cases, one essential epithet should be added: a glamorous, tabloid fairy tale, circulated among a million people, a phenomenon (or literary fact, to use Tynianov’s term) of 1920s-era bohemian culture that spanned the globe from San Francisco to Leningrad.

In this newspaper-oriented mass culture, the Poet’s and Dancer’s terrible fates were written not in blood, but in typographic font. And in this capacity, they are real and worthy of a scholarly attention. One should not be surprised that as sophisticated a connoisseur of Russian modernism as V. F. Markov (who obviously preferred the “authentic” Velimir Khlebnikov to the “superficial” Sergei) believed the fantastic legend of Esenin’s last will and testament, as related in the memoirs of the American impresario. Good cultural historians not only record rationally established facts and weed out fabrications, but also listen in, paraphrasing Alexander Blok, to the vulgar, popular “music” of contemporary myths and the most unlikely rumors, slanders, and mystifications.

Ultimately, what we might call the mystification industry speaks in its own “ridiculous” (mass-market) language not about things that actually happened, but rather about (ethe)real biases, aspirations, fears, and ideological conflicts — which it reenacts and sells to the world.

Ivan Narodny’s Last Abode: his home in Sharon, CT, and his “grave” (marked) at Ellsworth Cemetery (photo by Brent Prindle)