Jared N. Warren (PhD NYU, 2021) is a member of the academic staff of the Leibniz Institute of European History in Mainz, Germany.

Poland underwent several upheavals in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries that prompted extensive reflection about its borders and national belonging. A series of three partitions dismantled the Polish-Lithuanian state in 1795, its territories absorbed into Prussia, the Russian Empire, and the Austrian monarchy. When Napoleonic forces arrived in the Polish lands, the creation of a French puppet state, the Duchy of Warsaw, prompted hopes for renewed independence. These were partially satisfied with the establishment of a new Kingdom of Poland in 1815 that was dynastically linked to the tsarist Empire until the violent November Uprising (1830–1831) dashed Poles’ dreams of Russian benevolence. Each of these reformulations of Polish geography pushed Poles to reimagine what it meant to be Polish in the absence of their own state.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, Polish-speaking political and intellectual elites strove to restore the country to its pre-partition borders. The boundaries of the Commonwealth, established in 1569, had once covered much of today’s Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Belarus, and western Ukraine.

While contemporary stereotypes often identify Poles as necessarily Roman Catholics, Polish intellectuals and politicians in the early nineteenth century understood that the Poland they imagined was a territory whose inhabitants practiced a wide range of religions that included Roman Catholicism, Uniate (or Greek) Catholicism, Orthodox Christianity, and Protestantism, as well as Judaism and Islam. The statistics that circulated widely in the early nineteenth century identified almost sixty percent of the population of this space as non-Roman Catholics.

After the Partitions, the Polish elite continued to foster pretensions to this entire territory and its population, shaping how Poles imagined the relationship between religion and politics. Historians and sociologists have argued that the strong integration of Roman Catholicism and Polishness occurred relatively recently, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the early nineteenth century, on the other hand, many Polish elites understood that associating Poland too closely with Catholicism risked alienating parts of its imagined territory and population. Instead, Poles often depicted “Poland” as, by definition, multi-confessional. For instance, the poet Seweryn Goszczyński polemically declared in the early 1840s that “it is not possible at the same time to be both a good Catholic and a good Pole.”

The Roman Catholic hierarchy was similarly skeptical of the revolutionary politics that many Poles advocated throughout the nineteenth century. Many Polish political actors were anticlerical and responded negatively to Pope Gregory XVI’s condemnation of revolution in an 1832 encyclical that ordered the Polish clergy and faithful to obey their lawful ruler, the Russian tsar. The papacy’s memories of the threats that revolution and liberalism had posed to the Church’s temporal power during the French Revolution and Napoleonic wars meant that Polish revolutionaries, too, aroused its anti-revolutionary ire.

Before Catholicism became a dominant part of the Polish national imagination, Poles carefully crafted visions of Poland-Lithuania’s past that interpreted the Commonwealth as a bastion of religious tolerance. In the 1830s and 1840s, for instance, the socialist historian Jan Czyński celebrated Polish kings who “understood that Poland’s strength consisted in freeing the masses and in the widest religious tolerance.”

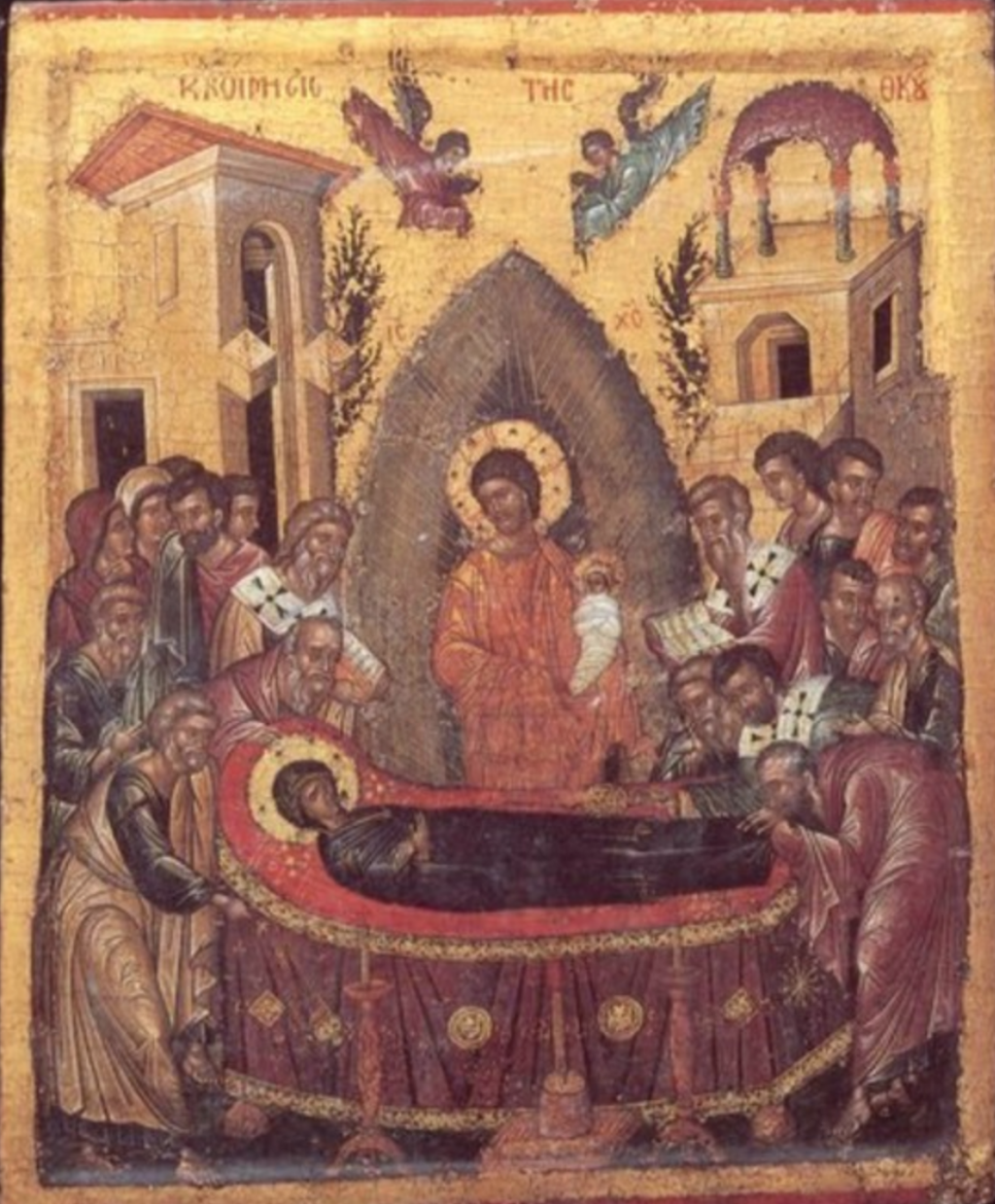

It was not just leftists like Czyński who sought to defend a multi-confessional Polish society. Conservatives, too, could emphasize religious tolerance within their political work, contrasting the Commonwealth’s historic religious inclusiveness against the intolerance of the Russian empire. The chief example in these arguments was the longstanding Russian persecution and complete suppression of the Uniate Catholic Church on the territories of the former Commonwealth.

The conservative prince Adam Czartoryski believed that Catholicism distinguished Poland from Protestant Germans or Orthodox Russians. At the same time, he believed that a future independent Polish state would of necessity guarantee the rights of all religions. “There cannot be true faith,” he declared in a speech in November 1840, “without freedom of conscience.”

These various attempts to grapple with the challenges of a religiously mixed population were part of a broader European political transition away from early modern practices of religious toleration—where the license to practice a given religion did not guarantee the same political status to members of different confessions—to a more modern system of protected legal equality.

The early modern Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had been an officially Catholic polity, but tended to be more tolerant of its other religious communities than most European states at the time. The Constitution passed on May 3, 1791, four years before the final partition of the Commonwealth, declared Roman Catholicism to be the “dominant national religion” while also guaranteeing the “freedom of all rites and religions in the Polish countries.” The primary privilege of Roman Catholicism was that its faithful were forbidden from converting to other denominations.

In the context of this transition between regimes of religious tolerance, it is unsurprising that a defense of tolerance did not imply that Poles viewed all religious confessions as politically equal. New hierarchies or relationships among confessions were being worked out.

Socialist and democrats in the first half of the nineteenth century sometimes ranked different religious confessions according to their ability to promote their desired political society. In their formulations, Protestants—seen as highly educated—were considered best suited for an enlightened future citizenry, followed by Roman Catholics, and Greek Catholics, with Orthodox Christians ranked lowest. This hierarchal understanding linked “backwardness” to the east and “enlightenment” to the west. The absence of an independent Polish state enabled such figures to foster dramatic fantasies of religious engineering.

In contrast to their treatment of Christian denominations, many of the Polish intellectuals, politicians, and publicists who commented on the Polish question selectively ignored or forgot Polish Jews in their writings. Sometimes, they depicted Jews as an oppressive economic threat to the Polish peasantry. Individual voices did, on occasion, combat such antisemitism. For instance, in the 1830s and 1840s, Jan Czyński advocated strongly for Jewish political rights, arguing that antisemitism weakened Poland’s social cohesion. He constantly excoriated his compatriots for their antisemitism.

In contrast to Judaism, Islam was sometimes seen more positively. Michał Czajkowski, a conservative novelist and diplomat who worked for the nobleman and statesman Prince Czartoryski, believed that Poles could consider converting to Islam if it enabled their ability to fight for Polish independence. Czajkowski himself converted in 1850 and during the Crimean War (1853-1856) led a Turkish legion against Russia. Other Polish thinkers in the 1850s explicitly argued that the defense of the predominantly Muslim Ottoman Empire and of European (Latin) Christendom against Orthodox Russia were compatible political goals.

Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, Polish elites cultivated a broad variety of perspectives on Catholicism and its relationship to Polishness. While Roman Catholicism did ultimately become prominent in Polish national politics, that outcome was never historically foreordained. Such a transformation required the emergence of stronger political and religious conflict after 1848, the hardening of institutional confessional boundaries, and a growing Catholic skepticism of religious tolerance in the second half of the nineteenth century. The rise of a more integrated Catholic nationalism was part of an ongoing renegotiation of the relationship between religion and politics in Poland that continues to the present.