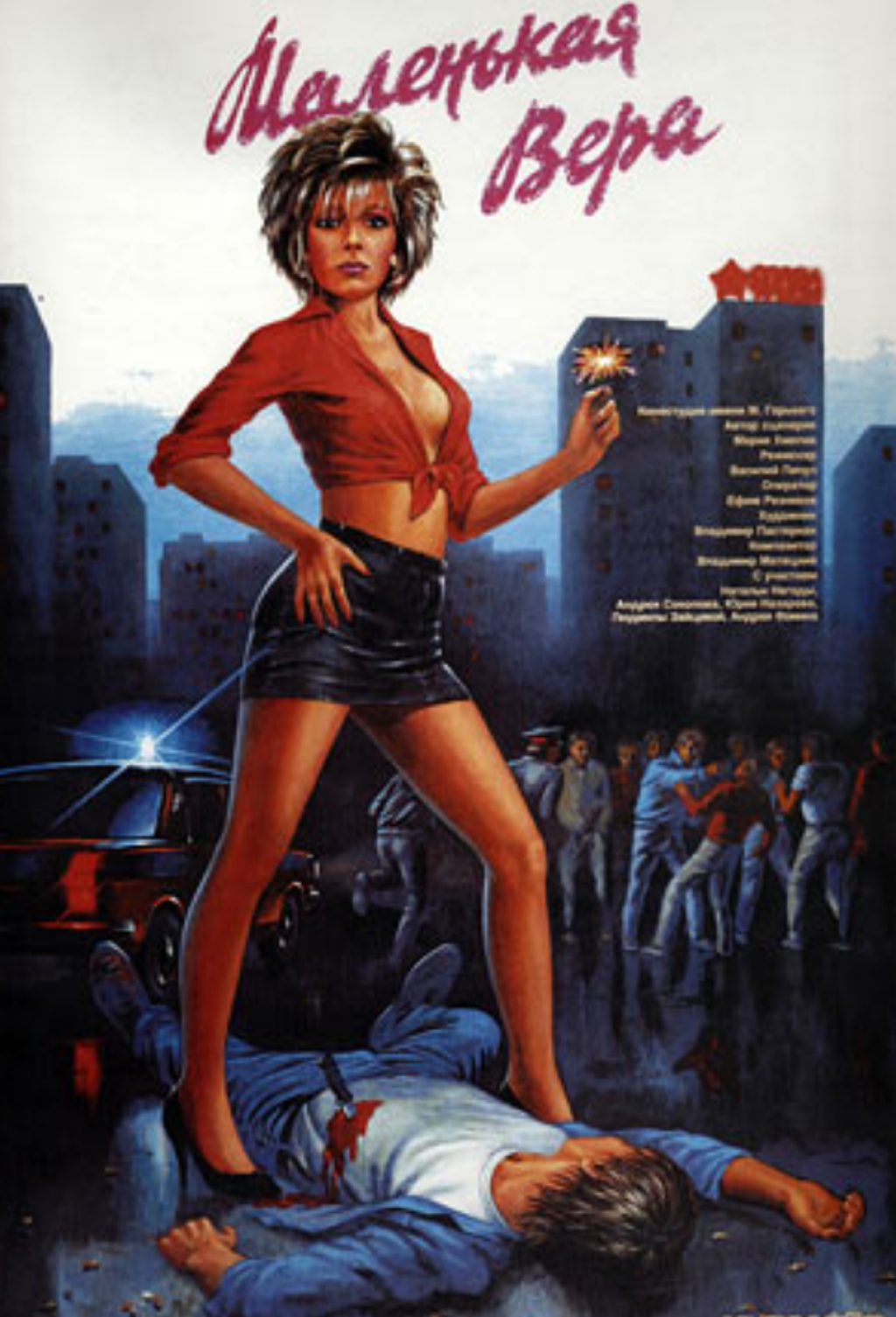

Above: The theatrical release poster for Vasily Pichul's smash hit Malen'kaia Vera (1988).

Svetlana Ter-Grigoryan is a doctoral candidate in the Department of History at The Ohio State University.

On May 12, 1990, President of the USSR Mikhail Gorbachev created the "Committee on the Development of Urgent Measures to Protect Public Morality.” This committee consisted of “moral experts” from the offices of the Ministry of Culture, the Prosecutor’s Office, the Supreme Court, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and several others governmental bodies. During perestroika, many felt the moral fabric of the country was under attack due to the sudden plurality of opinion and values made possible by glasnost-era reforms. The Committee met eight times over the course of 1991, painstakingly drafting “The Resolution for the Project on Urgent Measures to Protect Public Morality and Suppress the Propaganda of Violence, Cruelty, and Pornography.” Their meetings, resolution drafts, and feedback demonstrate that the Soviet state recognized the vital role that legislating pornography would play in defining the parameters of legal reform and personal freedom in the era of perestroika.

Gorbachev’s Committee was a response to a perceived morality crisis proceeding from the sudden influx of pornography, erotica, and violent media from the West. Although pornography remained illegal in the USSR, glasnost threw into disarray the state’s censorship bodies and created gray areas around the legal definition of freedom of speech. At the same time, glasnost exposed the country’s messy social realities of rising domestic violence and sexual assault rates. According to sociologist Igor Kon, sex offenses increased nearly 60 percent between 1961 and 1991, with the perestroika period alone accounting for 21.3 percent of that growth.

Commentators in the press discussed the state of moral decay and asked aloud if glasnost reform had inadvertently exposed citizens to Western debauchery during an especially vulnerable time. Ordinary people sent in letters to the Ministry of Culture and the Supreme Soviet, arguing that the growth of violent, often sexually motivated, crime must be connected to the growing presence of pornography throughout metropolitan cities.

From the 1917 Revolution through the NEP years of the 1920s, there were few legal restrictions on sexuality. Literature with sexual themes was popular during the NEP period and reflected the heated nature of the Bolshevik revolution. However, reproductive and sexual liberties such as abortion and decriminalized homosexuality were curtailed under Stalinism. All publishing was placed under the control of the state, which prevented the appearance of overtly erotic themes in literature or other media. Despite the crackdown, pornography flourished in the underground economy, and by the 1960s, there was a black-market cottage industry of homemade pornography. In response, the state formalized its ban on pornography by adding a statute (Article 228) to its criminal code which penalized the production, distribution, or advertisement of pornographic materials.

Gorbachev’s reform policy — glasnost — loosened the reins of censorship across the country and allowed for a greater degree of eroticism in state-funded media. It also legalized the production and distribution of independent media for the first time since the NEP period. Soviet films like Malen'kaia Vera [Little Vera, 1988], the USSR’s highest-ever grossing film, toed the line between erotica and pornography. Many independent publishers fully ignored the ongoing ban on pornography.

In the USSR, anti-obscenity laws existed, but were rarely enforced. Between 1986 and 1989, the number of people held criminally liable under Article 228 decreased by 81 percent. The lack of prosecution under Article 228 had an inverse relationship with the amount of pornographic materials entering the country. By the late 1980s, one could not walk through a metro station or city underpass in any major Soviet city without being bombarded by pornographic images for sale at every magazine and newspaper stand. Most were cut from Western magazines and Xeroxed, but some were higher-quality materials smuggled into the country from Europe and the United States.

Gorbachev's Committee agreed that enforcement of Article 228 was profoundly lacking. However, the body's deliberations were contentious from the beginning, with members disagreeing on all issues connected to regulating pornography. This lack of consensus is unsurprising in light of the Committee's ideological diversity: indeed, the inclusion of both abolitionists and libertarians guaranteed conflict. Some members openly objected to the very fact of the Committee's creation and vowed to sabotage its efforts. The libertarian stance held that further regulation and censorship, no matter where applied, would only strengthen the spirit of authoritarianism that perestroika sought to lessen.

Those who resisted renewed censorship efforts stated that they did so in the interest of protecting personal freedom and creative expression, hard-won victories of glasnsot. The Committee ultimately drafted fourteen separate versions of the Resolution before it was finalized on April 3, 1991, with each draft recognizing the concept of “personal freedom” to a greater and greater extent. Each draft began with a preamble that stated the Committee’s mission and the Resolution’s intent. Early drafts focused more heavily on addressing societal moral decay and policing media for the sake of protecting the youth, while later drafts of the preamble minimized focus on moral decay and dedicated more space to the idea of “inalienable rights” to freedom and creativity.

The Committee’s greatest challenge was in defining pornography, a prerequisite for drafting meaningful legislation against it. Even pornography abolitionists acknowledged the importance of erotic themes in art and literature and did not wish to return to a Stalin-era blanket ban. Finding the line between erotica and pornography was especially challenging in the era of glasnost, when citizens were bombarded with raunchy new domestic and foreign media that blurred the line.

The Resolution addressed these difficulties by creating an “expert commission” of “prominent members of the culture and art communities, psychologists, sociologists, lawyers, and other highly qualified specialists.” These experts were tasked with the arduous work of reviewing every piece of media, state sponsored and independent, for pornographic or grossly violent themes before approving them for distribution to Soviet citizens. Thus, the Committee avoided the impossible task of enshrining a definition of pornography into law and elected instead to create a cumbersome bureaucratic structure to approve media on a case-by-case basis.

The continued inability to clarify the definition of pornography undermined the Resolution’s proposals. Prosecution of Article 228 had fallen drastically during the glasnost years for the exact same reason: confusion around which media, exactly, were pornographic. The Committee’s efforts were doomed from the beginning, their Resolution another unsuccessful reform initiative in the months and years leading up to Soviet collapse.

The Committee’s failure to delineate pornography is central to understanding reform under perestroika. The state’s legitimacy ultimately came into question as every reform threatened to undermine the fabric of Soviet power, which was based on the idea of a social, political, and moral monopoly rather than on the plurality of opinions glasnost engendered. The conflict between the ideal of moral law and personal freedom exposed fatal weaknesses in the Soviet state, marking it as incapable of reform.