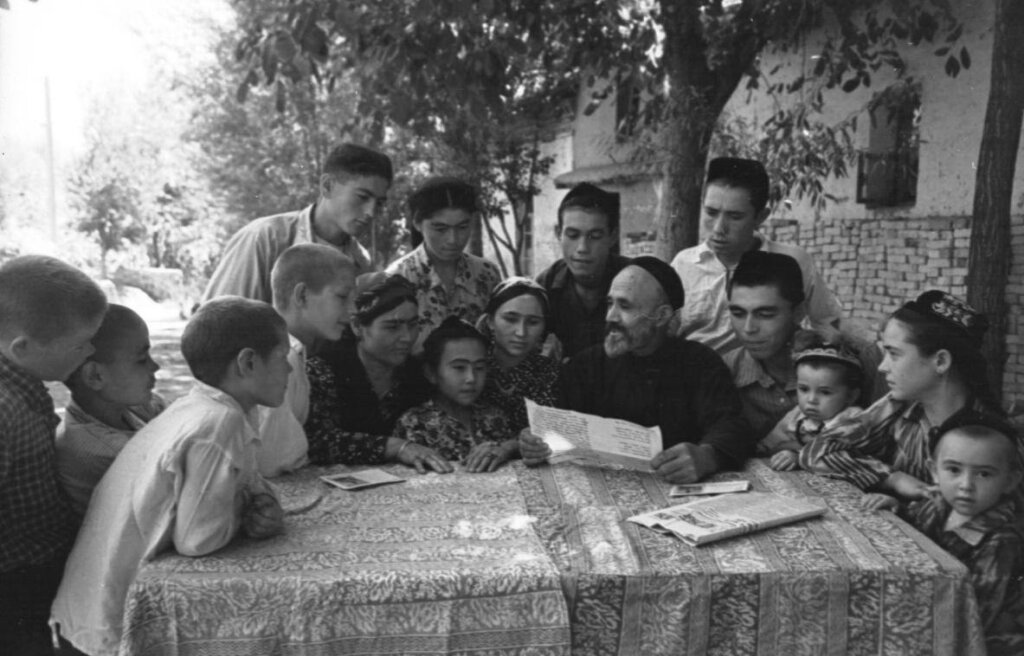

Above: The family of Akhmed Shamakhmudov and Bakhry Akramova,1955, Tashkent. Courtesy of O’zKFDDA, 0-33715.

This is Part I in a two-part series. Part II will follow on Thursday, 4/15.

Zukhra Kasimova holds an MA in Comparative History from Central European University in Budapest, Hungary. Currently, she is a PhD candidate in the History Department at the University of Illinois at Chicago researching Soviet Central Asian social and cultural history.

“The family of an Uzbek blacksmith identified as Shamakmudov [sic] may be the most multi-national in the world, the TASS news agency reported today. Akhmed and his wife adopted 14 children of soldiers killed in World War II including Uzbeks, Russians, Jews, Tartars, Moldavians, and Gypsies,” various American local daily news outlets reported in December 1964. Indeed, the main Soviet information agency, TASS, had run a short article on this Uzbek family as an exemplar of Soviet "friendship of the peoples."

During the war, the multinationalism and diversity of the Shamakhmudov adoptees was touted as an embodiment of the friendship among fifteen Soviet national republics. Despite their lack of education and limited Sovietization, the adoptive parents of these fifteen children were glorified in a poem, a book, and a film. Finally, they were immortalized in a city sculpture erected next to the Friendship of the Peoples Palace in Tashkent, capital of Soviet Uzbekistan. Bakhry Akramova was the first non-biological mother to be awarded a “heroine mother” order, aimed at granting agency and stature to formerly marginalized Central Asian women. During the Cold War and detente, Soviet propaganda further instrumentalized this family’s story to showcase Soviet internationalism and world peace efforts.

The Shamakhmudovs were one of many local families to adopt war orphans in the Uzbek SSR. Out of all these families, they were hand-picked by local authorities as early as 1942 to represent an “upgraded” version of the postwar Uzbek nation in the emerging new configuration of the multinational Soviet “family.” Their non-normative social characteristics notwithstanding, the Shamakhmudovs were favorably distinguished from many other Central Asian foster parents of even greater marginality from the perspective of Soviet modernization efforts. These latter families were either ethnic minorities, single parents (who thus compromised the trope of the “family”), or those living in “traditional” rural areas and could therefore not represent an exemplary “Soviet” model.

By adopting Slavic and other non-indigenous children, Central Asian families—impenetrable to Soviet discourse prior to the war—gained a chance at inclusion and active participation in the Soviet project through expansion of traditional “kinship” categories and the renegotiation of the relationship with the elder Russian “brother.” Family and kinship idioms played a key role in Soviet nation-building from the very beginning of korenizatsiia (indigenization) policies of the 1920s. Rhetorical constructs such as “brotherhood of nations” or “family of Soviet nations” coded the Soviet vision of “empire of nations” based on a peculiar social evolutionism.

As Francine Hirsch has explained, this vision implied the correspondence between a higher degree of modernity and a developed national consciousness and culture, which together served as a precondition for advancement to a yet higher, socialist, stage of social-economic development. Soviet nations were supposed to be national only in form and socialist in terms of ideological “content” of their respective modernities. Instead of national competition, they practiced “friendship of the peoples,” thus downplaying contradictions between nation-building and postcolonial class internationalism within the project of Soviet modernity.

By the end of the 1930s, the rise of state-sponsored Russian nationalism made this discourse more explicitly hierarchical by promoting the trope of the Russian people as the “elder brother” in the “family” of Soviet nations. Corresponding language was widely disseminated in state propaganda: “When the talented, freedom-loving, and courageous Russian people rose up to win their freedom…they were hailed as first among the equals by the other peoples of the USSR, just as brothers in a close-knit family, despite being equal, prioritize their elder brother.”

Echoing this discourse in his speech at the Eigtheenth Party Congress in March 1939, First Secretary of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan, Usman Yusupov, argued that “the Uzbek people can emerge victorious by following Red Moscow, the great Stalin, the Russian people.” In July 1941, he reaffirmed: “the Uzbek people know they owe all of their historical accomplishments, their freedom, and happiness to Moscow, to the great Russian people, the Bolshevik Party, and their beloved leaders Lenin and Stalin.” Like many Party leaders, Yusupov frequently and creatively adopted kinship tropes during the war, saying, for instance:

German Basmachi broke into the house of your elder brother—a Russian, and into the house of your other brothers—Belarusian and Ukrainian… the house of a Russian is also your house, the house of a Belarusian is also your house! For the Soviet Union is a close-knit family: although each lives in his own house, the land and household form an indivisible unity.

The persistence of kinship metaphors in official all-Soviet and Uzbek Soviet discourses illustrates the intrinsic connection between family as a real social institution and the imagined Soviet symbolic order. This series of links justifies my exceptional interest in the Shamakhmudov family, which was hailed by official propaganda both in Uzbekistan and in Moscow as an embodiment of the friendship of the fifteen Soviet nationalities — but who, at the same time, provided an authentic local idiom of this official trope from the vantage point of the Soviet “East.”