On November 27th, 2018 the Jordan Center hosted its event “The Vory: understanding Russia’s gangsters in their historical and political context,” a book talk with Mark Galeotti. Mark Galeotti is currently a Senior Non-Resident Fellow at the Institute of International Relations Prague, and is renowned expert of transnational crimes and Russian security. The event, as part of the Occasional Series, was introduced by Jordan Center director Joshua Tucker.

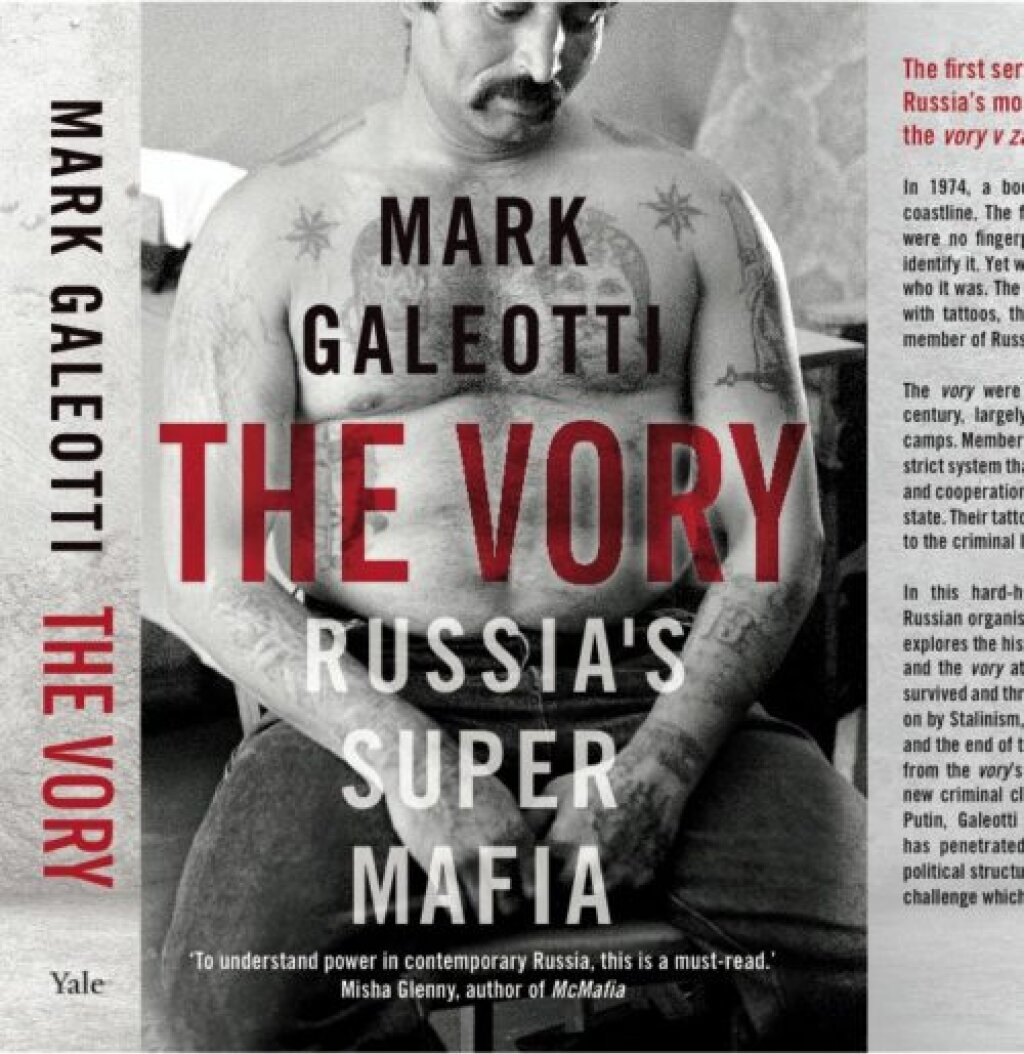

The talk concerned Galeotti’s latest book, The Vory: Russia's Super Mafia, which, as a result of Galeotti’s exhaustive research and personal encounters with Russian criminals, presents an in-depth historical account of Russia’s vory v zakone, or, thieves-in-law. Galeotti prefaced the talk with a personal anecdote in which he described a meeting with a Chechen hitman. Unlike criminals in other countries, Galeotti explained, Russian gangsters rarely express caution or practice self-censorship when speaking to journalists, as they are essentially protected by the law. The Chechen hitman spoke extensively about his life story, and Galeotti was struck by the extent to which the hitman “defined his criminal career in terms of the political environment.” During the hitman’s childhood, his family was deported by the Stalin regime, yet, he maintains no animosity towards Russians or the Russian state; this event in his life story simply made him “more tough,” and taught him that rules were defined by the individual. The hitman joined the army in his young adult years, fighting for the “very state that screwed him and his people over,” Galeotti said. At the time the conversation took place, the hitman was specializing in high value organized crime targets, such as godfathers and kingpins. In order to maintain financial stability, the hitman only needed to complete a few hits a year, a fact he used to rationalize continuing in this profession. Galeotti proceeded by explaining the paradigm through which the hitman saw the criminal ecosystem that he was a part of: organized crime, low crime and hackers were not a parasitic force, as much as they were an alternative economy, an alternative “parastate structure.” The hitman’s cultural cache, according to Galeotti, wasn’t simply defined by his kills, but also defined by his personality. Galeotti pointed to an entire internet fan base – online forums that rate various notorious criminals – as an example for a perception and culture around criminality in modern Russia.

The history of Russian organized crime, according to Galeotti, dates back to 19th century Russia, and largely sprung about through horse thieves in the rural areas and the rise of the bureaucracy in urban areas. Horses in the 19th century Russian provinces were both scarce and vital for survival, providing a very profitable opportunity for the thieves. If caught by the villagers that they stole from, however, the thieves were dealt with in the most savage of ways. Over time, a peasant rebellion grew in retaliation to the horse thieves, prompting the thieves to become more organized. Gangs of horse thieves began to swap horses with gangs from other regions, or sell them to the army, creating the the foundation for a criminal network. Through the medium of horse dealers, the first interaction whereby the state benefited from organized crime began to manifest. The second, and according to Galeotti, more successful form of “proto-organized” crime, largely took place in the slum neighborhoods and markets of Russia’s major cities – areas that the state largely neglected. This rise of urban criminality directly coincided with the rise of the Russian bureaucracy, and many urban criminals were simply fraudsters, who preyed on wealthy members of the aristocratic elite outside of their own community. The 19th century also gave rise to the first visual language of Russian criminality, primarily in the form of tattoos. The tattoos, according to Galeotti, served as “indelible signifiers” for the criminals, a substitute for identity papers. The blatant visibility of the tattoos, particularly on the fingers of the criminals, is a testament to how the thieves were eager to display their involvement in the criminal underworld. Like the Chechen hitman, and unlike members of other international gangs such as the Yakuzas, who hide their tattoos, the Russian criminals were never bothered by the idea of exposing their allegiances. The Russian vory wanted to parade the fact that they made a life choice to become a part of this subculture, the voroskoe “mir,” or world. This mir, according to Galeotti, was an entire culture, rather than an organization.

Under Stalin’s reign, the vorovskoy mir became significantly more interconnected and empowered than before, and this was largely a result of the Gulag labor camp system. Rather than an archipelago, as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn famously referred to the prison system, the labor camp system was, according to Galeotti, held together by a tight network. Criminals from all over regions of the country were placed in the Gulags, creating a network through which they were able to homogenize and disseminate their culture. As the years went by, the state began to see opportunities in co-opting the criminals as guards and wardens for cheap slave labor, adding yet another economic element to the criminal underworld. But because it was engraved in the old code that any collaboration with the state was strictly prohibited, criminals that turned to the state were branded enemies of the criminal world. Eventually, a wars spawned between the “traditionalist criminals” and the turncoat “scabs,” which became so volatile that many of the Gulag camps were forced to shut down. The state would offer its discreet support for the “scabs,” who ultimately triumphed, and rewrote the criminal code to allow state collaboration. From this point onward, it became entirely acceptable to collaborate with the state, as long as the vory profited from the exchange.

After Stalin’s death, and the subsequent opening of the labor camps, a new generation of vory began to permeate the Soviet underworld. The post-Stalinist state continued to maintain a powerful grip on society, yet corruption began to pervade its ranks. Corrupt officials, therefore, became the perfect targets for this new breed of vory. By the 1970s, black market entrepreneurs and corrupt Soviet officials were regularly communicating through intermediaries. Anti-alcohol legislation, introduced under Mikhail Gorbachev in 1980s, was perhaps the most empowering moment for these Soviet criminals. By illegally smuggling and selling alcohol, the vory essentially established their very “own economic sector.” According to Galeotti, the vast majority of Soviet citizens never blatantly encountered organized criminals, only if in the form of service providers, such as the taxi driver who would provide alcohol for a wedding. The liberalization of the Soviet economy during perestroika provided even more lucrative opportunities for the vory. These opportunities ultimately gave birth to the gangster-businessmen – the providers of gray area services.

With the collapse of the Soviet state, many of the criminals began entering elite positions. The infectivity of the authorities allowed for criminality to roam freely on the streets: terrified and outgunned, police would often patrol for no more than fifteen minutes. Eventually coinciding with Putin’s rise to power, the untethered criminality that defined Russia in the 1990s began to diminish. Galeotti noted, however, that the appearance of safer streets in Russia shouldn’t serve as an indicator of the disappearance of organized crime. “The rules of the game,” Galeotti explained, “have simply changed.” During Putin’s first term, high level security and police officers would have sit-down meetings with gangsters, explaining to them that any acts that resembled a challenge to the state, or embarassed the state, would result in severe and harsh crackdowns. The gangsters, left without a choice on the one hand, and an opportunity to continue their activities on the other, agreed to the terms. According to Galeotti, this negotiatory relationship between the Putin-led state and the criminal world shouldn’t come as a surprise, as Vladimir Putin had famously negotiated with the Tambovskaya mafia during his time working under Anatoly Sobchak. Under Putin, the state therefore became the “the biggest gang in town,” the one to which all organized crime groups were forced to adhere. But Galeotti also brought to attention that referring to Putin’s Kremlin as a “Mafia State,” is inadequate, as it implies that either Vladimir Putin runs organized crime, or organized crime runs Putin, which, because the state and organized crime are separate entities, is incorrect.

Galeotti concluded the talk with a prognosis on the future of criminality in Russia, claiming that “russia is going on the right directions,” and that the effects of Putin’s severe clampdown on organized crime are becoming increasingly visible. Many of the gangsters attempt steer their children from following in their own footsteps, as the climate no longer allows them to commit crimes with the freedom they had in the 1990s. Social mobility within the criminal underworld has withered, and many of the younger criminals in their 40s are becoming tired of having to serve as lieutenants. The general societal attitude towards crime and corruption is likewise worsening. Opinion polls show that there is a distinct shift in what society regards as an “acceptable level of corruption,” and although, according to Galeotti, that “may not sound great,” the reality shows that the the system is slowly maturing.

One of the questions raised during the Q&A session concerned the ethnic and national component to Russian organized crime. Galeotti responded by saying that the ethnic dimensions of organized crime are most often highlighted in the news: Georgians and Chechens are generally associated with organized crime in contemporary Russia. The reality, however, is that Georgian organized crime gangs are actually very multiethnic, often resembling the Koza Nostra during the American bootlegging period, that had the likes of Meyer Lansky and other Jewish members working within these “Italian” criminal ranks. As for the Chechens, Galeotti stated that they are often notorious for their “implacability,” and that the “Chechen criminal” has almost become a brand name. Smaller non-Chechen gangs will often appeal to the nearest Chechen godfather, in an attempt to associate with a larger Chechen criminal group to bolster their own reputation. Part of the reason why Russian criminal organizations never had a major ethnic component, explained Galeotti, was that the state has always been conscious of the risks of ethnic crime gangs, and has made particular efforts to prevent them from truly emerging. Galeotti cited the example of the two Chechen wars, during which the Russian authorities warned Chechen criminal gangs to not collaborate with the the Chechen rebels. “Because the Russian state has always been so formidable,” the Chechen godfathers complied with the orders.