This week, All the Russias is pleased to feature thesis profiles from graduating M.A. students in the Department of Russian and Slavic Studies. This is the first post in the series.

Rachel Angelica Engle specializes in Russian and Ukrainian art history and its relation to contemporary politics.

Above: Interior image of the Clementinum Complex, Prague

My combined interest in Ukrainian art and history led me to explore a brief segment of Ukraine’s nationalist narrative through analysis of an art collection. This research developed into my Master’s thesis, titled "Ukrainian Interwar Nationalism: The Prague Period." Through the NYU-sponsored Global Research Initiative Fellowship in Prague, I had the privilege of working with the National Library of the Czech Republic and their Collection of Art Works by Ukrainian Émigrés, which is composed of precisely 463 inventory units created by 43 members of the Ukrainian Studio of Plastic Arts in Prague.

This Studio and the art within it was bombed in 1945 in the American Air Force’s air raid over Prague. While this air raid has since been considered accidental due to Prague’s similar appearance to Dresden, it nevertheless succeeded in destroying nearly a hundred historical sites, including the Ukrainian Studio of Plastic Arts. Most of the collection was destroyed, and what remained was significantly damaged. The art that remained in satisfactory condition following the 1945 attack was sequestered into the basement of the historic Clementinum, a library comprised of several baroque-style buildings. In 1948, after the Communist takeover in the Czechoslovak coup d’état, what was left of the museum’s collection within the previously bombed structure was targeted for its political nature and either destroyed or transported to Moscow, where it was housed in undisclosed locations.

The specific assets I studied for my thesis research were rediscovered in 1998, by employees of Prague's Slavonic library. The Slavonic Library, founded in 1924, is part of the Clementinum complex, now a branch of the National Library of the Czech Republic. The Slavonic library is responsible for the processing and preservation of nearly 800,000 assets of Slavic ephemera, of which 463 were discovered by library employees in several dozen abandoned boxes and plates in the Clementinum basement.

Part of the challenge I faced when examining these works was to develop a collective and meaningful analysis while remaining conscious of the collection's arbitrary nature. The works exist cohesively, but are not intentionally grouped — in other words, the collection constitutes a unity not because of choices by a curator, but through happenstance. I sought to overcome this arbitrariness by categorizing the artworks with respect to artist, style/genre, thematic motif, and general time period. In the process, what emerged was a breakdown of the "democratic"/ "authoritarian" binary that characterizes most analyses of nationalism. Instead, I came to understand nationalism as a spectrum running between nonconformity and assimilation.

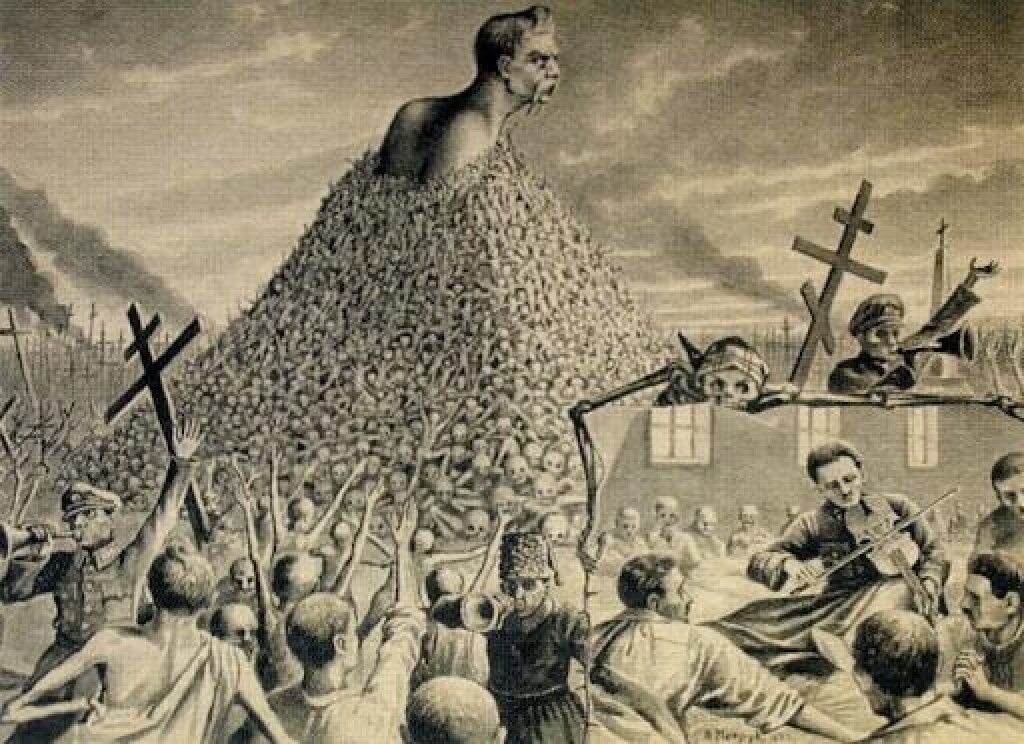

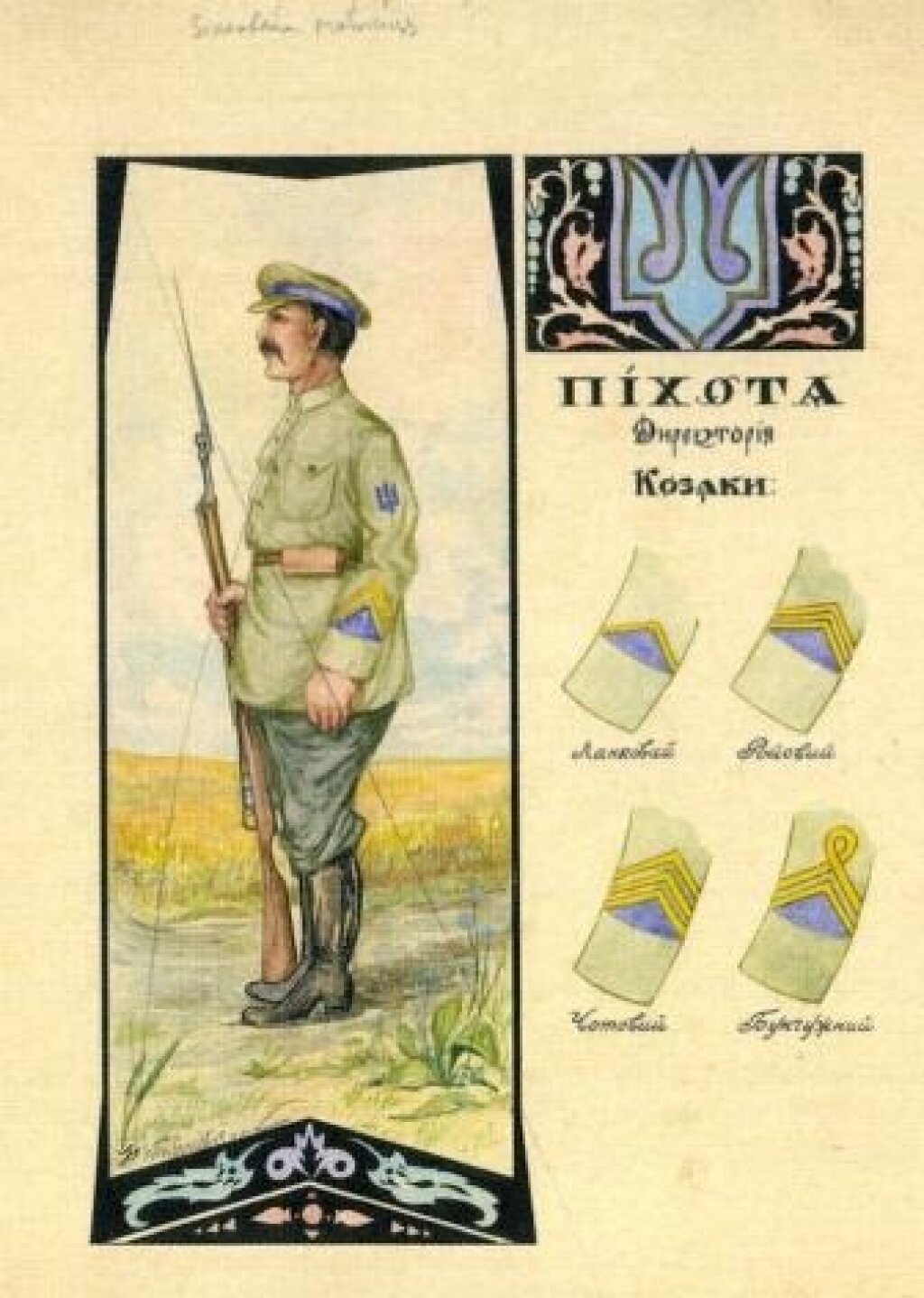

Within the Collection of Art Works by Ukrainian Émigrés, this spectrum manifested itself in an eclectic array of stylistic experimentation. As some of the stylistically diverse images from the collection demonstrate, the artists expressed their nationalist views in various ways. Some artists, such as Mykola Bytynskyj, hearkened back to literal images of Ukrainian unity and pride, while others attempted to shed light on the loss and atrocities experienced by the Ukrainian people in recent years — as in The Eternal Memory of Ostap Nyzhankivsky and Death in the Quadrangle.

Part of what makes this collection significant is the simple fact of its survival amid the violence of the Second World War and ensuing events. Its content illuminates a period of historical anomaly. The treatment of ethnic Ukrainians following the First World War was remarkably cruel in most of Eastern Europe, Czechoslovakia being a notable exception. The acknowledgement of a separate Ukrainian national identity was repeatedly suppressed in order to avoid disrupting various larger national agendas. The version of Ukrainian authoritarian nationalism that retaliated against this treatment has received extensive scholarly treatment, but this collection helps provide an alternate narrative of a less-extremist democratic nationalism that enjoyed a brief and troubled existence. The politically welcoming and socially hospitable environment of Czechoslovakia in the interwar period allowed Ukrainian émigrés to express a form of democratic nationalism through fine art. The Ukrainian Émigré collection thus serves as an example of the potential for nationalism to exist peacefully and unobtrusively under amicable conditions.