This is Part I of a two-part series. Part II will follow on Wednesday, 2/5.

Natalia Koulinka is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History of Consciousness at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her recent article, “A Portrait of the Worker against the Backdrop of the Soviet Union’s Collapse,” appeared in the journal East Central Europe 46(1): May 2019.

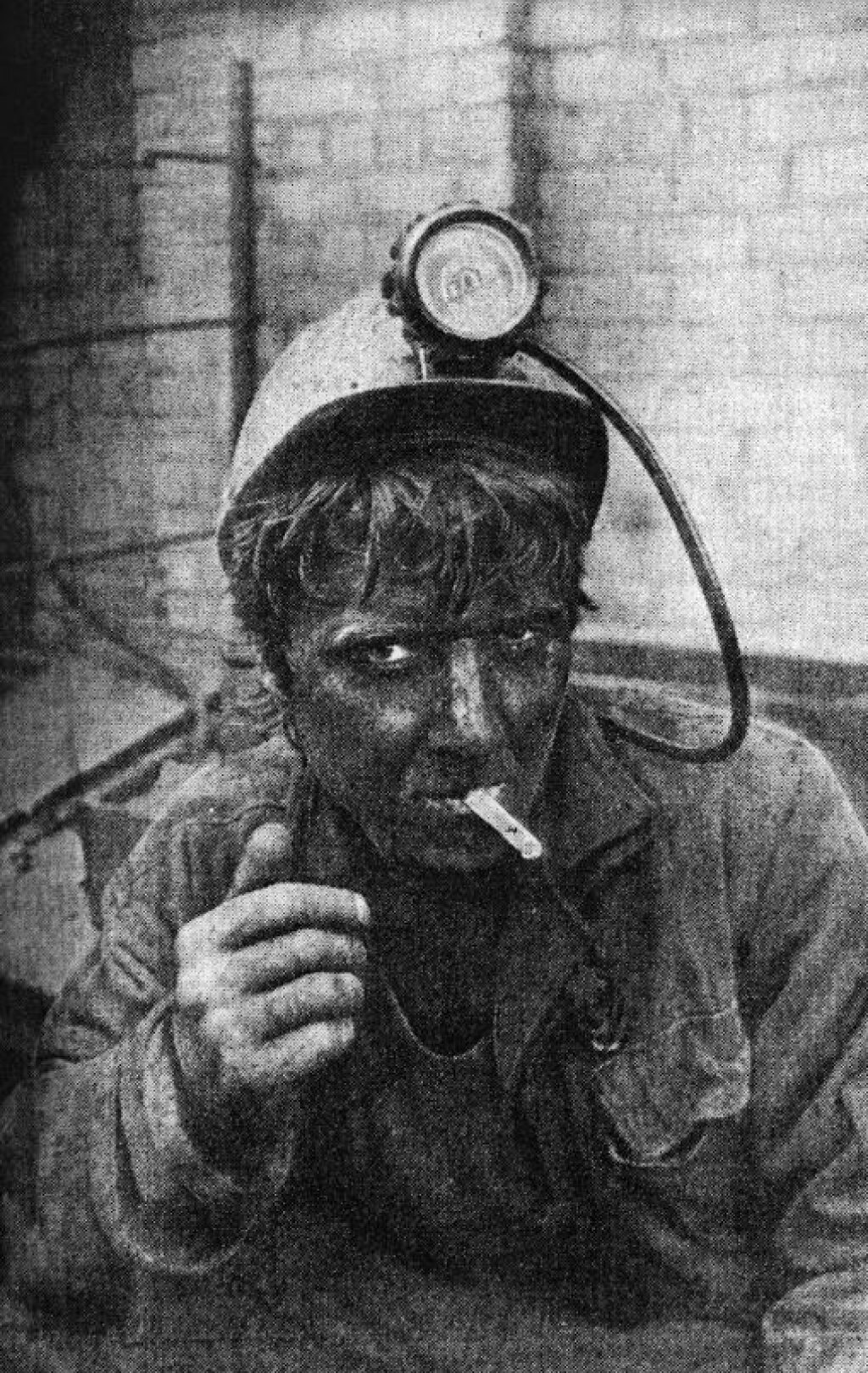

The first wave of miners’ strikes in the Soviet Union started on July 10th of 1989 in the Kuzbass. It was followed by a second wave that rose up during early March of 1991 in the Donbass. It is widely believed that the strikes contributed to the Soviet Union’s collapse when the strikers allied themselves with Boris Yeltsin — at that time president of the Russian Federation — and demanded the resignation of Mikhail Gorbachev and the Union’s government. The strikers won.

Later, however, recollections emerged in which miners questioned the results of their struggle. For instance, in 2009, Mikhail Krylov, who in 1989 co-chaired the Donetsk Strike Committee, recalled in an interview to the newspaper Segodnia [Today], “We never pursued the goal of Soviet collapse. We were against the people in power, rather than the country.” Although this change in miners’ attitude could be interpreted as nostalgia, it seems equally likely that their bitter feelings are caused by the unresolved question of why their struggle for freedom and democracy ended in massive socio-economic inequality.

I attempted to answer this question based on an analysis of miners’ demands, as well as the discursive context of the late Soviet 1980s and early 1990s. In particular, I engaged two leading All-Union periodicals — the daily Izvestiia [News] and the weekly Literaturnaia Gazeta [Literary Gazette] — focusing on articles that either reported on the strikes or discussed the socio-economic and political changes engulfing the country.

My analysis led me to three conclusions. First, the strikes of 1989 displayed some attributes of class struggle. Second, the strikes of 1991 represented a classical merging of a workers’ movement with that of the intelligentsia. At that time, unlike in the October Revolution of 1917, the intelligentsia took the side of neoliberal, market-economy values. My third conclusion relates to the discursive context of the late 1980s and early 1990s, a crucial feature of which was its amalgamation of Soviet discursive streams with new values and ideas. That intertwining added to the confusion, so typical of the time, and facilitated a series of substitutions in understanding such concepts as "democracy," "the free market," and "bureaucracy," all of which played a prominent role in contemporary discourse.

The most startling example of this confusion is a speech by a disappointed miner at a 1991 meeting in the Kuzbass. The speaker, quoted by newspaper, Izvestiia, stated:

I've worked in the mines for 35 years. Over those years, I've earned many merit badges, diplomas, and regalia, but don't have the means to retire and must continue to work. All because I, like the rest of us, don't own any property. That is why we appeal to the People’s Deputies of the Russian Federation: to do everything possible in order to eradicate historical injustices and give us back our mines, factories, plants, and land.

What strikes me most about this statement is the juxtaposition of the miner’s confidence that factories, mines, and land should belong to the laborers, on the one hand, with his call for a return to private property, on the other.

In his Hot Coal, Cold Steel (1997), Stephen Crowley finds an explanation for this confusion in the lack of any “direct experience of the market,” which left the strikers with no other option than interpreting a new situation “through the dominant [i.e. socialist] ideology.” In other words, Crowley concludes, they “reached into their cultural toolkit and pulled out mental templates that created a shortcut to understanding a market economy.” In many instances, Crowley adds, the confusion also resulted from “the uncritical use of the West as a utopia.”

The newspaper Izvestiia is a rich source of such examples. For instance, in a 1989 interview, a famous Soviet playwright compared the Soviet bureaucrat with his or her Western counterpart. He said that nowhere in the world “is there such bureaucracy — uncultured, incompetent, unprepared for managing, but overconfident in taking upon him or herself the right to decide” — as we had in the USSR. In contrast, the playwright referred to a hypothetical, honest Western bureaucrat who would immediately resign if he heard the criticism to which Soviet bureaucrats have been subjected. The playwright concluded the interview by pointing to an overall “lack of morality and culture in [Soviet] society” and connecting this problem with the high cost of the Bible in the Soviet Union. “‘We are the only country in the world,’ the playwright maintained, ‘where the Bible is sold for such a high price (in the West, one can find it in the bedside drawer of every hotel).’”

The avalanche of positive opinions published by Soviet newspapers about life in the West did not mean that they remained unquestioned, as the following example from Izvestiia illustrates. In 1989, a reader wrote to the newspaper:

In the central press (and not only there), much has been said about standards of living in the United States. However, when it comes to numbers, most observers and commentators avoid giving a straightforward answer to the question: ‘How much do things cost there?’ I tried to find relevant literature in Leningrad bookstores, but there was none … What can I conclude from the fact that a nurse earns two thousand dollars a month? How much is that? In other words, how much is their rent? What is their monthly food budget?”

Though such doubts appeared occasionally in the newspapers, it is safe to say that they tended to be perceived as the last vestiges of Soviet propaganda, not as invitations to approach newly popular ideas in more balanced ways.