Meghanne Barker is a Lecturer in the Department of Education, Practice and Society at University College London. She is the author of Throw Your Voice: Suspended Animations in Kazakhstani Childhoods (Cornell University Press, 2024).

This is Part II in a three-part series. Part I ran on 9/24 and Part III will appear tomorrow, 9/26.

Throw Your Voice a Northern Illinois University Press book published by Cornell University Press. Copyright (c) 2024 by Cornell University. Used by permission of the publisher.

GETTING LOST

A young, reddish dog—a mix of dachshund and cur—very foxlike in face, ran up and down the sidewalk and looked uneasily from side to side. Occasionally she stopped and, whining, lifting first one chilled paw and then another, tried to account to herself: How could it have happened that she got lost?

...

If she had been human, she probably would have thought: “No, it is impossible to live like this! I must shoot myself!” But she thought about nothing and only wept.

—Anton Chekhov, “Kashtanka” (1887)

Kashtanka’s puppeteer, Bolat, walks onstage at the Almaty State Puppet Theater with the short-legged, long-bodied dog in puppet form. A tall, thin young man with black hair and a close-trimmed beard, wearing blue pants with suspenders and a black shirt, Bolat narrates Chekhov’s lines to the audience, speaking about the dog as if she were not there, as if the long rods attached to her back did not render her body an extension of his. “She remembered quite well,” Bolat tells us of Kashtanka, “how she had passed the day and how, in the end, she had found herself on this strange sidewalk.”

The book chapter from which this post is drawn examines tropes of displacement—in puppetry, at Hope House, and in Kazakhstan’s history—to reveal a recurrent ambivalence surrounding such movements. The rift is painful, yet it creates the possibility of new connections and a promise of restoration. Animation has a unifying effect, while forced movement breaks social relations. These two types of displacement seem quite different. Yet, rupture is necessary for novel recombination. Projection in time and place offers hope during periods of disconnection. Reminders of the children’s lost homes reinforced their understanding of their condition in Hope House as a temporary one. Rather than dwelling on the moment of loss, they learned to anticipate the moment of recovery, and thus to understand the present as a state of waiting for a desirable future. At another scale, Kazakhstan has been the site of major rupture and loss for families, due to exile, imprisonment, and forced resettlement. The worst took place under Stalin, but Kazakhstan’s characterization as the middle of nowhere extends before and after this period. Portraying the country as empty steppe helped justify acts of exile and forced settlement. These acts led to familial separations and losses through death, making the orphaned child a salient figure. Those living with temporary loss exist in a state of waiting, a part of the self elsewhere. Shared histories of loss motivate others—of return, of healing, and of reunion.

Just outside of the capital city is the museum dedicated to ALZhIR. The women imprisoned there were guilty by association: the prison camp, which operated from the 1930s to the early 1950s, housed women whose brothers, fathers, or husbands had been accused as enemies of the people…In a letter on display at ALZhIR, a child who has been separated from his mother writes to her. The author of the letter assures his mother he is fine. He works to maintain a connection, despite their separation:

“Hello dear mamochka why did you write me letters. mamochka you don’t know where is papa. Mamochka I am studying in the second grade. Mamochka I was sick for a very long time with ringworm. Mamochka I am alive and well. Mamochka, you write that you don’t have paper. mamochka I am sending to you(?). mamochka, I miss you very much. There’s nothing more to write.”

The letter is unsigned, but the gendering of the past particles and adjectives indicates that the author is a boy. If he is in second grade, he would have been around eight years old. The first line is a puzzle, as if the child forgot to negate the writing of letters, for the mother’s reasons for writing would seem obvious, if it had happened. Later, the child mentions that the mother lacks paper, which raises the question as to how the boy knows this. Nonetheless, it seems he is sending her paper so that she might be able to reply. Rather than the parent offering a modest gift to the child (as occurred when parents visited Hope House), the child sends a small gift to his mother. It is paper that she will, presumably, return to him in the form of a letter, so his gift offers the promise of a sustained relationship via correspondence.

Despite many uncertainties, I can be sure of the letter’s addressee. She is Mamochka, “Mommy.” The boy has taken care to write her name at the beginning of every line, a kind of incantation. Barbara Johnson describes poetic authority as “the capacity to call.” Her description of the power of apostrophe, the poetic calling out to an absent party or to a personified object, is fitting here. She argues, “He doesn’t even have to say anything about X; he merely has to ‘ring’ it. In fact apostrophe can be mere sound, amplified by the laws of sound waves, ‘redoubled and redoubled’ or ‘sounding and resounding.’” The phatic (attention to channel), emotive (attention to speaker), conative (attention to addressee), and poetic (attention to form) inhere in the repetition of the name, mamochka .

Various senses work in concert to make this word appear on the page, through the visual, aural, and haptic acts of reading and writing. For a child in the second grade, writing would still be new enough to require special care. He writes with blue ink. His handwriting is fairly unsteady, and there are a few errors. Writing becomes a way of performing a “kinetic melody” of the repeated word, as the Soviet psychologist Alexander Luria described. We can imagine a hand—a small hand—gripping a pen, moving it over the paper, ringing this woman’s title, again and again, through contact between the instrument and the paper that will bear its trace.

She was, of course, not the only mamochka at ALZhIR. According to the displays at ALZhIR, small children of the women were sent to a special orphanage, Mamkin Dom, “Mama’s House,” where they died by the thousands. They were buried in a cemetery nearby, Mamochkino kladbishche, “Mothers’ Cemetery,” named not for the inhabitants, but for the women who, when free, would presumably come to visit their children’s graves. The museums of KarLag and ALZhIR are full of stories of children and mothers. To the boy writing the letter, however, his is the one Mamochka. He is careful to interpellate her as such, no fewer than nine times in the course of his brief, but careful, epistle.

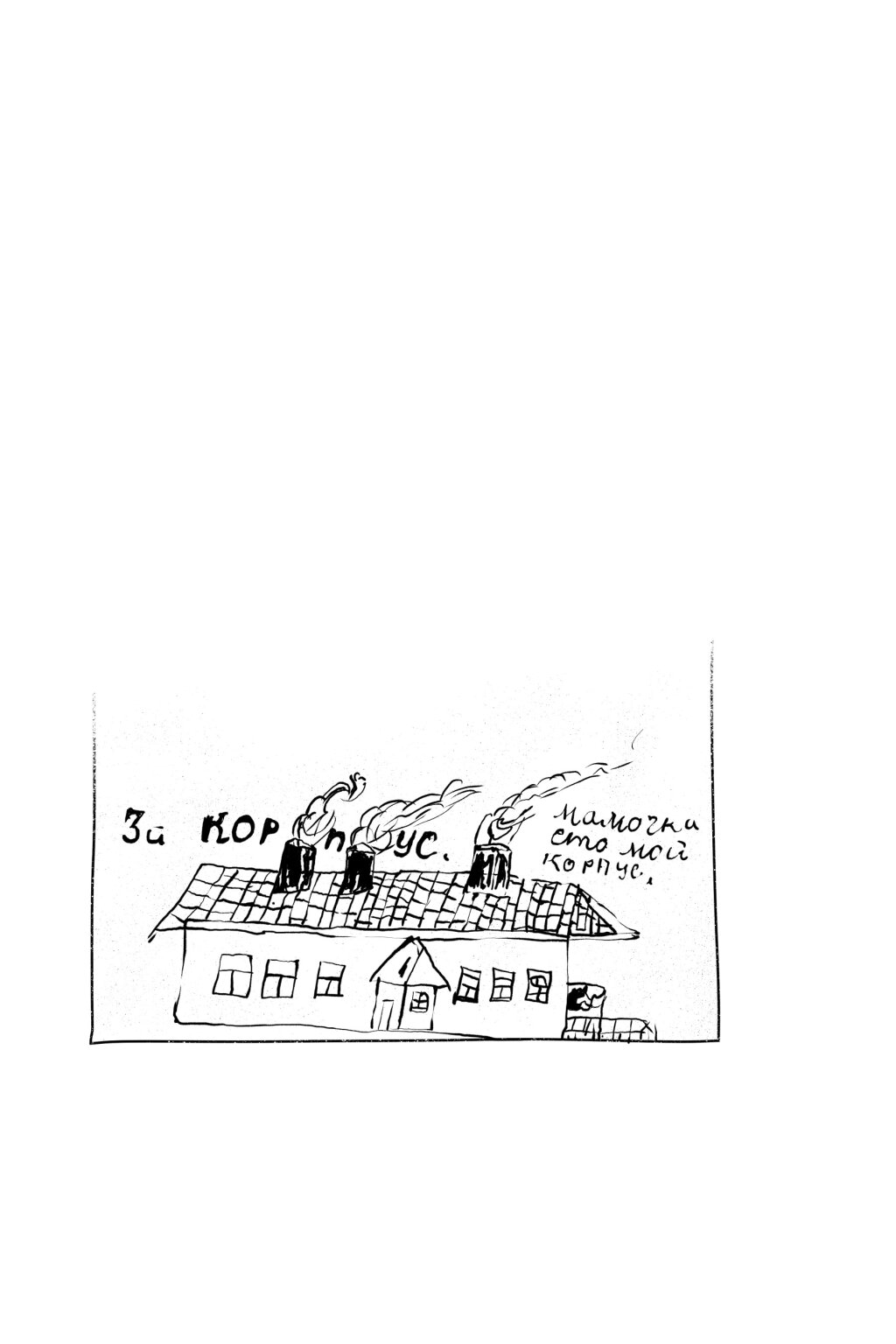

Unlike a photograph, the letter offers the mother a narrative, however compact, of suffering and rehabilitation, for the boy was sick (bolel), but is now alive (zhyv), and healthy (zdorovyĭ). At the bottom of the page, the child has drawn a long house with shingles on the roof and three chimneys with smoke coming out. Between the chimneys the child has written, in large block letters, 3i KORPUS, or “3rd building.” Just to the right of the last chimney he has written, “Mamochka this is my building” (Mamochka eto moi korpus). He doesn’t write, “This is my home.”