Meghanne Barker is a Lecturer in the Department of Education, Practice and Society at University College London. She is the author of Throw Your Voice: Suspended Animations in Kazakhstani Childhoods (Cornell University Press, 2024).

This is Part III in a three-part series. Part I may be found here, and Part II here.

Throw Your Voice a Northern Illinois University Press book published by Cornell University Press. Copyright (c) 2024 by Cornell University. Used by permission of the publisher.

The perceived emptiness of the Kazakhstani steppe helps outsiders (and government planners) to overlook and erase evidence of those who were there before—whether natives or exiles—and of those who remain after exiles have gone home. This is a common trope of settler colonialism—figuring the land as wild, untouched, or virginal, and either ignoring the previous presence of humans or aligning them with the wilderness, waiting to be tamed. Just as histories of particular groups or places disappear, intimate memories can slip away as well. Literary analyses of Chekhov’s story of “Kashtanka” have argued that it is all about issues of memory. On her first night away from her first home, Kashtanka remembers the carpenter and his son, Fedyushka, vividly. After a month, however, “in her imagination appeared two vague figures, not quite dogs, not quite people, with physiognomies friendly, dear, yet unintelligible . . . and it seemed to her that she had somewhere sometime seen them and loved them.” As memories become more dreamlike, the faces of the first master and his son transform.

The amount that the children at Hope House recalled of their time at home with their parents was unclear. According to research on “infantile amnesia,” children’s memories of specific events (their anecdotal memory) in their first years will recede gradually. As five-year-olds, the children of Hope House might remember their first year or two with their families, but they would not be expected to keep these memories by the time they were twelve or thirteen . Moreover, within Hope House, the loss of the parents wasn’t acknowledged as a memory in the past. Caregivers instead treated children as living in an ongoing state of missing, which was then enveloped in a narrative of healing via return.

At Hope House, the children’s play frequently made use of breakage to give way to something new, revealing an ability to cope with loss and to exploit the new possibilities that rupture presents.

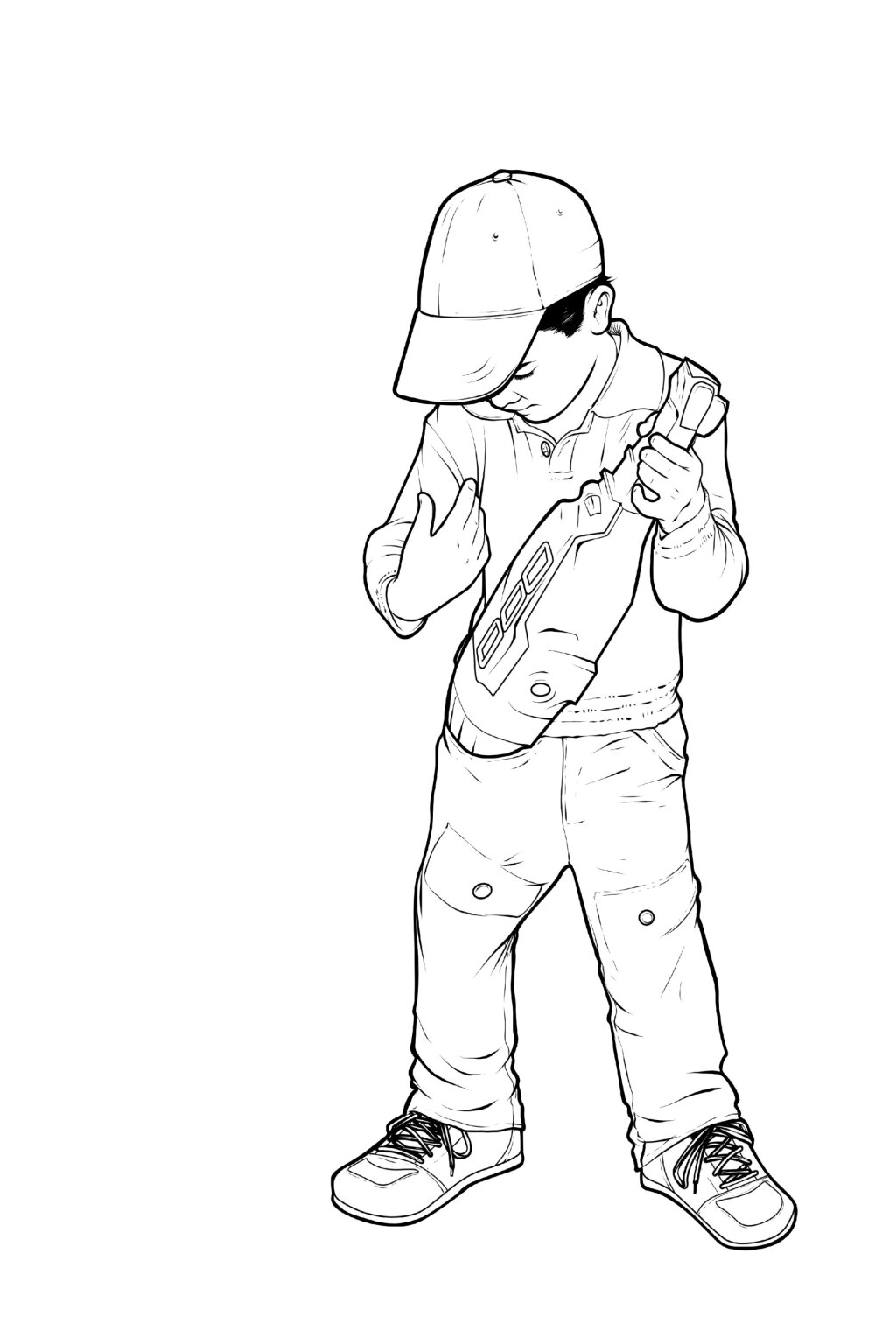

The day I filmed Nurlan giving the model sentence in class about the deferred toy his mother would promise him, he was far more outgoing on the playground than I had ever seen him before. In the video I captured outside that day, he is at first in the background. However, he quickly attracts my attention because he is holding a toy helicopter by its tail and bowing across it with a stick. The helicopter’s rotor system is missing, and he has turned it into a musical instrument—perhaps a violin, or perhaps a qobyz, a traditional Kazakh instrument praised for its sad sound… He throws down his bow and turns the helicopter to a horizontal position. He begins strumming it with his hand: it is suddenly a guitar or a dombyra. He moves the helicopter from his left hand to his right, making it vertical again, but continuing to strum. He picks the bow back up, switches from one hand to the other, the whole time singing what was nonsense to my assistant and to me: “Ala bali pa pa aha la la ua fa fa fa . . .”

Zhamilia, one of the twins, wants to play with Nurlan. The two of them go to the cupboards in the group’s outdoor playhouse to seek other instruments. Nurlan finds an object that once held other parts. Probably once a drawing board, it is now just a piece of blue plastic, with grooves in the middle where other parts have fallen off, and a small hole in the corner. Zhamilia has a miniature pinball game. Back behind the playhouse, Nurlan props one foot on a toy tractor, which he uses as a kind of footstool. He and Zhamilia hold their respective plastic rectangles vertically, in their left hands. They beat them with their right. Nurlan sings a song that is nonsense. Their teacher, Saltanat Apai, stands nearby and rehearses a text with another boy for an upcoming performance. She does not tell them to stop playing, but she leads the other boy by the hand around the corner of the playhouse. Nurlan falters in his song. The boldness he displayed earlier with the helicopter seems to have diminished, perhaps because he sensed his teacher’s annoyance at their impromptu concert in her own practice space. Zhamilia also loses her nerve, banging on her toy a couple of times but then transitioning from playing it as an instrument to playing with it as a pinball game. She watches the parts move around inside as she pushes the buttons. As Nurlan stops his own song with an “oy,” he smiles shyly. He holds the blue piece in front of his mouth and then brings it up to cover his whole face. With this, the frame of their play as fellow musicians is broken.

This loss of footing leads Nurlan to reorient to a new game. He notices a small hole in the corner of the rectangle and puts his eye up to it. He says “Meghanne Apai,” his voice high and singsongy, and he waves to me. Zhamilia rises and stands in front of Nurlan, working to reestablish his attention to their music. Nurlan looks at her through the hole, as Zhamilia again turns her toy vertical and bangs on it a few times. Nurlan lowers the blue plastic from his face and says something to Zhamilia that I cannot make out. Zhamilia drags her instrument on the ground and walks away from him, Nurlan calling to her as she leaves, “I’m like Meghanne Apai!”

“You’re like me?” I ask.

Having shifted the frame of play—albeit with the same object—he has moved from the music-making endeavor he shared with Zhamilia to a project of image making that aligns him with me. He confirms this move by switching from Kazakh to Russian to answer, “This is my camera” (eto moia kamera). I normally spoke Kazakh with the children, but Nurlan was beginning to speak a bit of Russian. He practices with me. He makes grammatical mistakes that he would not make in Kazakh. He says to me, “Snimite kamera,” by which he could either mean that he wants me to film (snimite s kameroĭ) or that he wants me to lower the camera (snimite kameru). Since I am already doing the former (filming him), I do the latter as well: I squat down to his level. He counts, in Russian—raz, dva, tri—pushes an invisible button on his blue rectangular camera, and lowers it from his face. He turns it around and points to a rectangular hollow space within his instrument. My picture is there, in that empty space, according to his game, and he shows it to me. He gets up so that I can show him the pictures I have taken of him in return. The clip ends. After Nurlan has looked at the footage of himself, he says to me, “And you’ll take this to America and show it to people and tell them, ‘This is my friend Nurlan.’” I tell him that this is what I will do, even if I will change his name.

Before, my camera blocked an easy mutuality of gaze because it came between my eyes and those of Nurlan and Zhamilia. At the same time, it oriented them toward my camera and toward me as a spectator, even as their playing together created alignment through the parallelism of their actions. Nurlan’s shift from playing with Zhamilia to mimicking me enables him to establish a mutuality of mediated gaze. This corresponds to Mazzarella’s description of constitutive resonance as “a relation of mutual becoming rather than causal determination.” Nurlan is not merely captured by me, but I am also captured by him. Nurlan’s act creates a moment of equivalence with our shared gaze and capturing, and with the photographic artifacts produced afterward which we show to each other.