This post is part of the Introduction to Unstuck in Time: On the Post-Soviet Uncanny, an ongoing Tuesday/Thursday summer feature on All the Russias. It can also be found on Eliot Borenstein’s website. To get email announcements about new posts, please write to eb7@nyu.edu

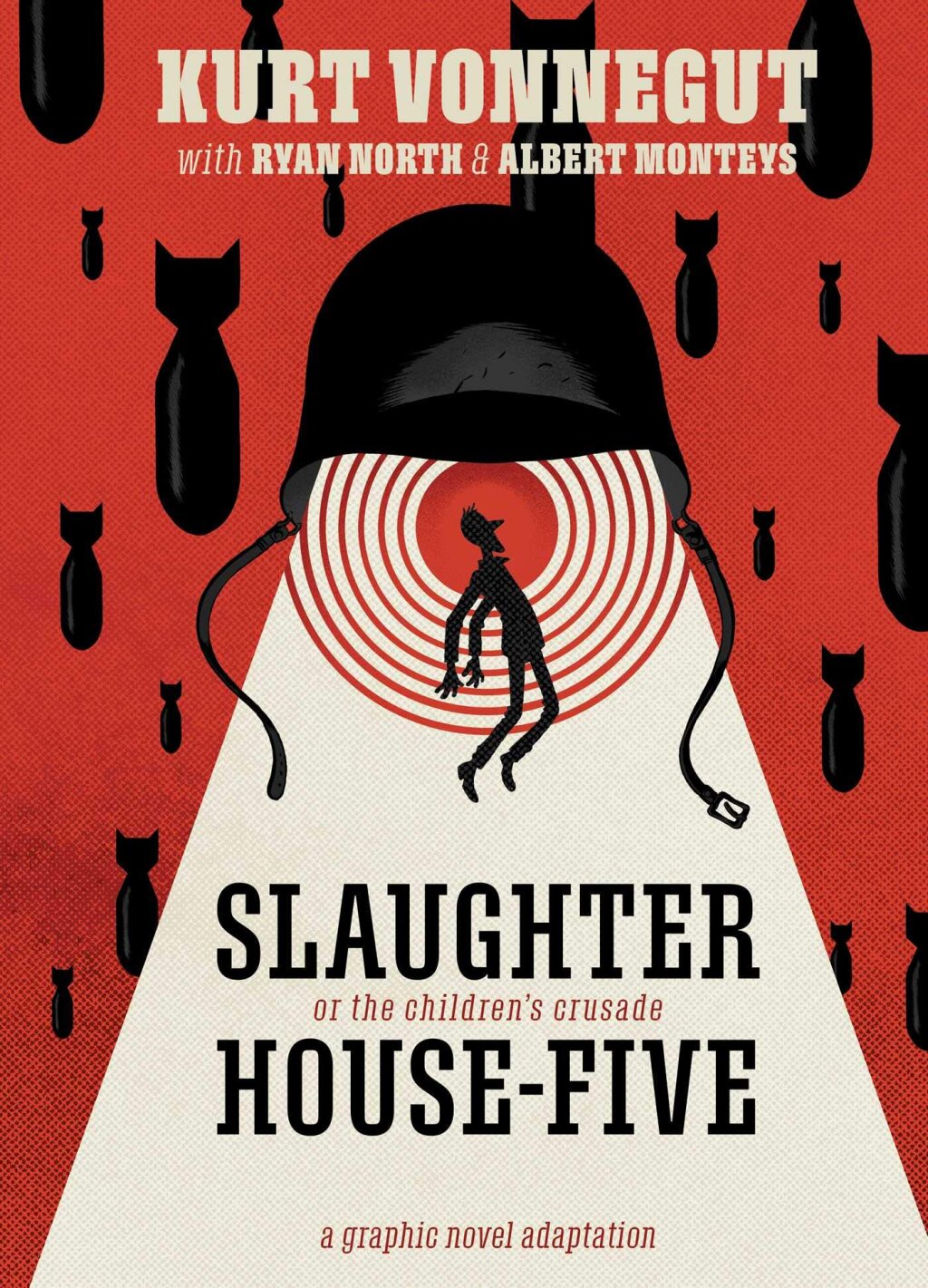

Like the book you are currently reading, Kurt Vonnegut's 1969 novel Slaughterhouse-Five contains multiple beginnings, as if the author is not quite ready to get started. According to the end of Chapter 1, the book starts in Chapter 2, with:

Listen:

Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time.

Billy has gone to sleep a senile widower and awakened on his wedding day. He has walked through a door in 1955 and come out another one in 1941. He has gone back through that door to find himself in 1963. He has seen his birth and death many times, he says, and pays random visits to all the events in between.

According to the novel, Billy Pilgrim died in 1976. Had he lived ten more years, he could have encountered his fictional heir, Jon Osterman, the physicist in Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon's Watchmen who, after being transformed into the godlike Dr. Manhattan, moved back and forth along his personal timeline in much the same way Billy did. Both Billy Pilgrim and Dr. Manhattan are jolted out of linearity by a catastrophic event: Billy in response to his experience of the bombing of Dresden, and Dr. Manhattan as his complete disintegration and self-reconstruction in a freak lab accident. In other words, they have each been displaced by trauma. Certainly Billy's frequent returns to his time in World War II resemble the flashbacks that plague veterans suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, while Dr. Manhattan's flat affect and indifference to humanity might, in a less science fictional mode, suggest a variation on shell shock.

Recognizing the risk of straining the metaphor beyond its breaking point, I nonetheless submit that the Soviet collapse loosed Russia from the bonds of linear time. Not literally, of course; as all the discussion of clocks a few pages ago demonstrates, empirical time continued to be tracked. Years followed one another in the customary sequence, and human bodies continued to age (in the cases of the most vulnerable, they probably aged precipitously). But the 1990s was a temporal derailment, one that sent pundits racing for historical precedent: the Time of Troubles, obviously, but also the Russian Civil War, the New Economic Policy, and the fall of Rome, among many others. Experienced as a time out of time, it would retroactively be cordoned off as a strictly delimited period of timelessness to which no one would wish to return. Its end, however, was not entirely a return to linear time.

Much of Russia's cultural production in the twenty-first century suggests that, even if it put an end to the Time of Troubles that preceded it, the Putin Era has not been a straightforward return to linearity. Certainly, the longstanding tendency to connect the current moment with a historical precedent has been intensified. The commemoration of the Sixtieth Anniversary of the Soviet victory in World War II seemed designed to make the Great Patriotic War feel contemporary. Where the Fiftieth anniversary in 1995 had numerous living veterans to celebrate and congratulate, the sad truth was that, with the passage of time, the commemorations would eventually be taking place in their absence. Thanks to the initiative of three journalists, the 2012 commemorations in Tomsk featured a parade of younger people displaying pictures of relatives who had served in the war. They called themselves the "Immortal Regiment," and by the next year, similar demonstrations were mounted throughout the Russian Federation.

As it happened, the spread of the "Immortal Regiment" coincided with the outbreak of war in Ukraine (the fighting in Donbas began a little more than a month before Victory Day 2014), facilitating the governments propaganda campaign to frame the fighting as a replay of World War II. [2] Ukrainian nationalists were "Banderites" (the name of the anti-Soviet Ukrainian nationalist forces who fought on the side of the Germans), as if Ukraine had somehow kept Nazis in reserve, to be awakened in an emergency by breaking their glass container. The following year (2015), Russian motorists proudly displayed bumper stickers saying "1945--we can do it again." By the time the coronavirus hit Russia in 2020, Putin's habitual invocation of Russia's historical triumphs had turned into a self-parody:

Everything passes and this will pass. Our country has gone through many serious challenges: When tormented by the Pechenegs and the Polovtsians Russia has handled them all. We will defeat this coronavirus contagion.[1]

The manipulation of Russian historical precedent for present-day political gain is rather clear-cut, as is the prominence of nostalgia in post-Soviet Russia. Indeed, the study of Russian nostalgia is something of a scholarly cottage industry, producing stellar work by Birgit Beumers, Otto Boele, Svetlana Boym, Milla Fedorova, Ilya Kukulin, Maya Nadkarni, Boris Noordenbos, Sergei Oushakine, and Olga Shevchenko, among others. Mark Lipovetsky's "post-sots" paradigm for art that uses the tropes of socialist realism without necessarily importing the ideological content, is also an important framework for understanding post-Soviet reappropriations of the past. But I propose something a bit different.

Notes

[1]“Putin Sets Off Meme Storm by Comparing Medieval Invaders to Coronavirus Quarantine,” The Moscow Times, April 9, 2020. The translation of Putin’s remarks in this article renders “Polovtsy” as “Cumans.” This is an acceptable translation, but, given all the words play involve “Polovtsian,” it is confusing. I have replaced “Cumans” with “Polovtsians” in this particular quote.

[2] See Maksim Hanukai, “Resurrection by Surrogation: Spectral Performance in Putin’s Russia.” Slavic Review 79.4 (2020): 800-824 .DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2021.6