This is Part II in a two-part series. Part I may be found here.

Fiona Bell is a literary translator and scholar of Russian literature. Her writing has appeared in Full Stop, Asymptote Journal, The LA Review of Books, and elsewhere. She is from St. Petersburg, Florida, but currently lives in New Haven, Connecticut, where she is earning a PhD in Slavic Languages and Literatures at Yale University.

The theater is another sort of therapy circle. The audience’s sympathy for the Man fills the room. We might as well be holding Styrofoam coffee cups as we listen to him. Even when he is sitting next to me, delivering his monologue to my right cheek, I notice several women in the room, including the Woman, looking at us and smiling. Their eyes follow the Man. I sense more than sympathy—there’s affinity, maybe even attraction. Are people into Pozdnyshev? How twisted. Although, abusers do tend to be charming. In No Visible Bruises, her recent book about domestic violence in the United States, Rachel Louise Snyder explains that these people must be captivating to ensnare partners in the first place. We expect abusers to be angry and taciturn. In reality, most of us would enjoy their company at a party.

It’s easy to pity the Man, too. Pity is weird. We happily extend it to strong figures but we’re stingy with the weak, with actual “victims.” Crucially, women are not immune to this way of thinking. I saw this on my train ride to Moscow. I also saw it two years ago, when Elena Mizulina, a member of the upper house of the Russian parliament, said that domestic violence “is not the main problem in families, unlike rudeness, absence of tenderness and respect, especially on the part of women.” And this strange phenomenon—women who protect their abusers—isn’t foreign to Russian thought. In his 1922 discussion of Fyodor Karamazov, the philosopher Lev Karsavin writes about how “the victim’s feeling of unjust humiliation is often replaced, unexpectedly and involuntarily, by pity for the rapist, as if he didn’t enjoy himself, but suffered, didn’t rape, but experienced violence himself.”

In the theater, it’s much harder to focus on the Woman, who is nearly always shaking and stuttering. She makes me anxious in the same way that nervous little dogs do. Even after my pseudo-victimhood in the first few minutes of the show, I find it hard to empathize with her. My pity for her is mixed with disgust.

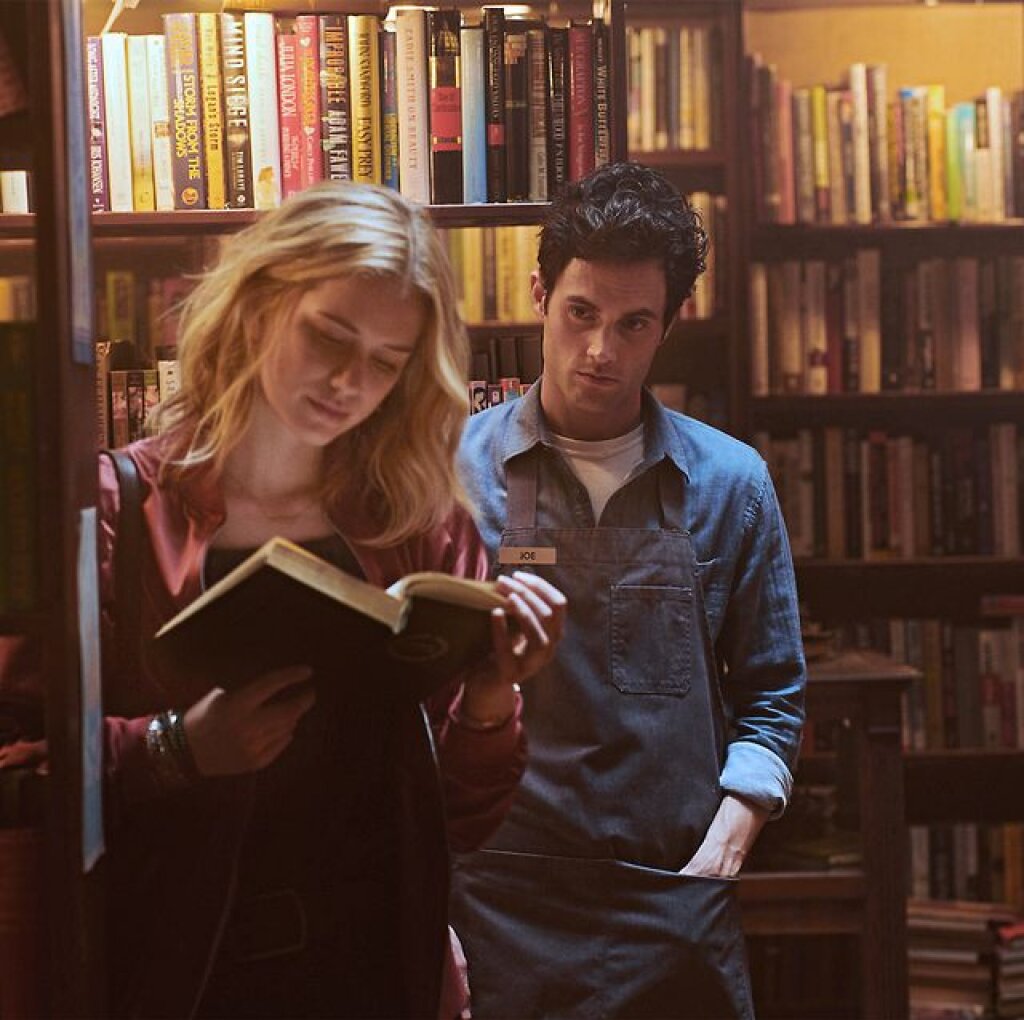

Maybe we fear the two-dimensionality, the passivity of victims. Maybe, in the abuser’s capacity for both violence and suffering, abuse and victimhood, we affirm our own complexity as human beings. Ilya Vinitsky suggested that this fascination with abusers began with Western literary depictions of Satan, from Milton to Byron. This figure is trying to take vengeance against God and the angels. In the Romantic era, he targets the woman who ruined his faith. This trope continues, of course. The examples are countless, but I keep thinking of the 2018 TV thriller You, narrated by a mild-mannered bookstore owner who becomes obsessed with a woman. His voiceovers are positively Pozhnyshevian. Our fascination with abusers—and I say “our” as a woman—is robust.

And so, in the economics of pity, women still get sixty-six cents to a man’s dollar. Isaeva’s play and Nazarov’s staging are both structured on this unbalanced model of attention. The Man tells his story and the Woman barely speaks. I counted: her lines make up six percent of the script. The Man speaks directly to the audience, while the Woman delivers her lines directly to the Man. In fact, she often assumes the position of an audience member, perching on the benches next to us. When she does speak, she often says phrases that Pozdnyshev attributes to his wife—a puppet in the Man’s narrative. Kate Manne is helpful here. In the imagination of a misogynist, she says, one woman can serve as a proxy for or representation of other women. That’s why it’s important that the Woman in this play is a stranger, a blank slate. The Man is able to imagine her as his wife and punish her for his wife’s supposed crimes. Nazarov doubles down on puppetry in the moment when the woman runs away, leaving her shoe, and Man uses the shoe as a puppet for his wife.

When the shoe proves capable of fulfilling the Woman’s role—a virtuosic understudy!—I realized how lifeless the Woman had been in the first place. While the show’s acting style was basically naturalistic (with vocal behavior, movement, and speech that we see “in real life”), there were other theatrical traditions at play. When Nazarov and his actors talk about their characters as “archetypes,” the “quintessence” of the sexes, for me he invokes a sort of non-naturalistic masked theater tradition. Incidentally, this is what Kate Manne is arguing: the misogynist recognizes the woman as human, but only insofar as she wears the mask of care, love, and kindness. Once she takes off that mask, he retaliates.

But the real feat of this play is its ending. The Woman, perhaps in puppet mode, performs a vocalise of the first movement of Beethoven’s “Kreutzer Sonata.” They kiss, then the Man pushes her away. He uses extra benches to build a platform. It looks like a bed. He sits her down on the bed and starts removing her clothes. She looks behind her, where the audience is sitting, once over each shoulder, as if to say, “Wow, can you believe this is finally happening for me?” When the Man settles onto her, though, she starts resisting, screaming, and crying. Her head hangs upside-down off the “bed” and she looks again at the audience. She mutters, “killed his…” “I hate you,” “I’m not scared.” She directs all this to the audience and finally says, “all of you, you, you, you” while pointing her finger at them.

As she mutters, the Man says, “I realized what I’d done.” This is Pozdnyshev’s phrase to his interlocutor after he narrates the murder of his wife. In raping this stranger, the Man repeats and represents his earlier murder of his wife. This scene is more progressive than the rest because it equates rape to murder, acknowledging the violence of sexual violence. In this scene, too, the Woman addresses the audience for the first time. It’s as though the entire production has taken place in the mind of the Man until this moment, when it becomes truly omniscient.

It’s also a reversal of what we’d expect in a rape culture. Usually the Woman would be shamed but, even during the act, she shames the onlookers. For the entire show up until this point, the bystander effect has been in full swing. Now, for the first and last time, the spectators are asked to take responsibility for the violence against the Woman. (Not that anyone spoke out or stopped the Man—we all knew the rules, after all.)

After the rape, the Woman comforts the Man (recall Karsavin here). Then they take up their former positions: him muttering incoherently and she reading her prayer book and looking in her compact mirror. The end of the play looks like the beginning. In the casualness, I see Nazarov’s project again. This age-old battle between Man and Woman is bound to repeat itself. It’s hardly worth notice. Everything runs on a circular track. (And the actors, too, will perform this violence again tomorrow—at a matinee and in the evening.) But there’s also something radical about depicting the banality of sexual violence. Rape, a regular occurrence, is one in a series of violent acts against women in our society, a society that dissuades viewers/bystanders from taking notice of these acts or their victims.

I used to think that theater made it impossible to ignore living human bodies. This was its medial superpower. Although readers of Tolstoy’s Kreutzer Sonata have no access to the wife’s perspective, I thought, at least theater spectators see the body and hear the voice of the Woman. But it’s not that simple. The Woman is actually quite easy to ignore. In the end, when she wags her finger at us, we seize up and feel a rush of guilt. But then we leave the theater—just as Tolstoy’s narrator and I left our conversation partners when we disembarked our trains.

Violence is everywhere on Moscow’s stages. And, though little has been written about it, domestic violence has become a common subject in the New Russian Drama movement. It’s no wonder why: in 2017 the Russian Duma voted to decriminalize domestic violence. In 2018, the three Khachaturyan sisters came under investigation for killing their sexually abusive father. In response, documentary theater artists responded with two new plays: Elena Pavlova’s Сестры по крови and Teatr.doc’s Три сестры, which were staged in the same year. In the 2019 issue of Theater magazine, Natalia Zaitseva recounted the proliferation of plays on these topics, including her own, Абьюз.

Despite all this interesting activity, it’s The Kreutzer Sonata, this conservative adaptation of a classic, that’s haunting me. And I think this suggests an important consideration in contemporary theater studies. The Moscow theater scene is dominated by adaptations of canonical literature. Even if we wanted to, we can’t leave the nineteenth century behind. And there’s nothing more interesting, I think, than the way contemporary theater makers reckon with nineteenth-century ideas about domestic violence, the ways they repurpose them within and for a society that is beginning to witness what has long been in plain sight.