The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

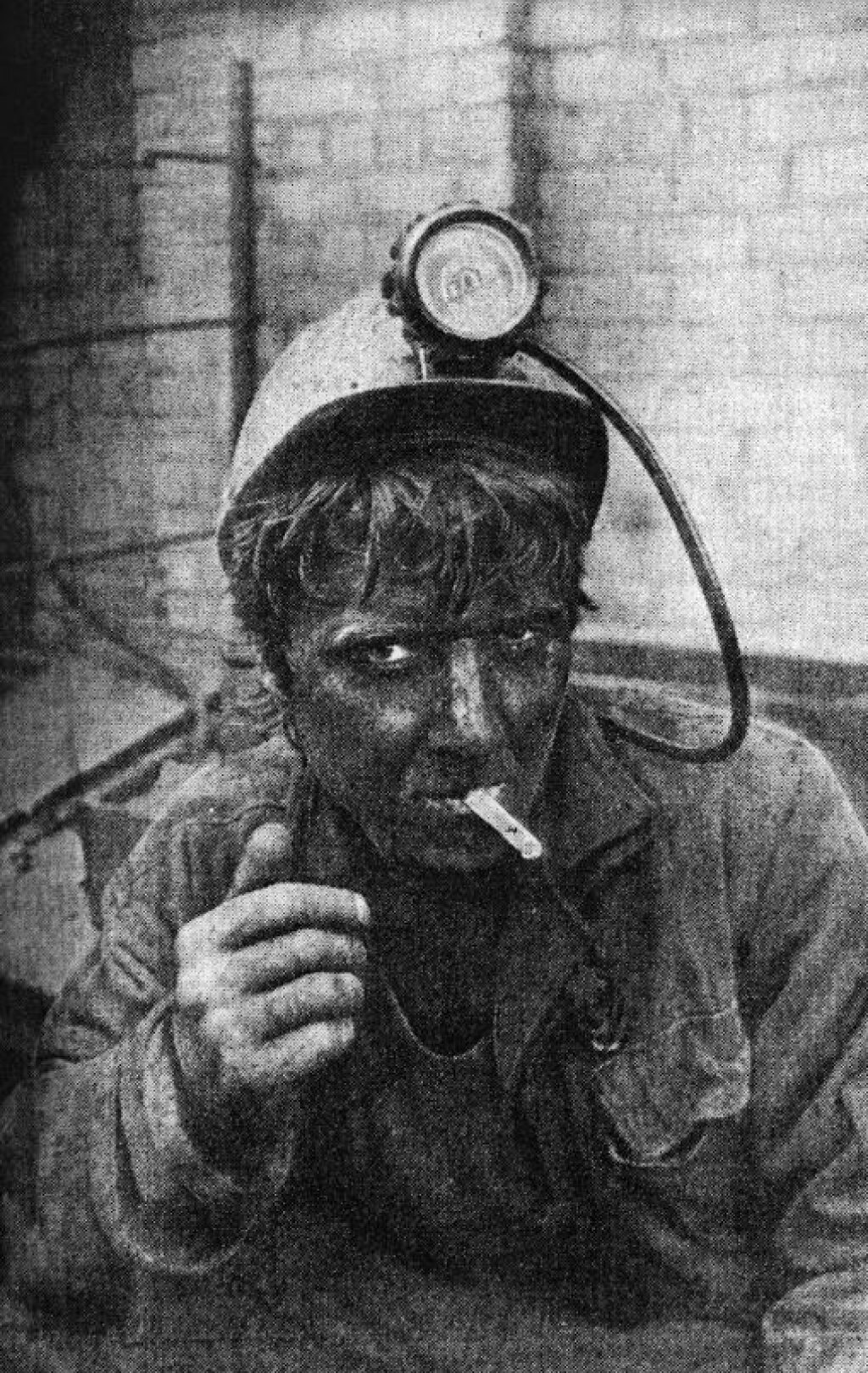

Above: Iurii Nikitin, Vzryv (Explosion),1998, 99 × 149 cm. Oil on canvas. Ukrainian National Chornobyl Museum, Kyiv. Courtesy of the Ukrainian National Chornobyl Museum.

Hanna Chuchvaha is an adjunct assistant professor at the University of Calgary. Her research focuses on several fields including print culture, women art collectors, and the art of trauma in Eastern Europe.

In 2022, Ukraine won the Eurovision song contest with the poignant composition “Stefania,” performed by the rap group Kalush. The official video for “Stefania” was filmed in Bucha, Borodyanka, Hostomel and Irpin, four Ukrainian cities that suffered from shelling and outrageous atrocities resulting from Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine. This song, which contains the elements of lullaby, is an ode to mothers protecting their children. As the description on the official Kalush Orchestra YouTube channel states, “although there is not a word about the war in the song, many people began to associate the song with Mother Ukraine.” The video first premiered on May 15, and by the end of August, had been viewed over 36 million times.

Set against the background of ruins of shelled Ukrainian cities, the video features silent portraits of women dressed in military uniforms, holding children. These women-warriors shield children lost amidst overpowering destruction. They also personify mothers who have left their families to fight against Russian aggression, a message that resonated with millions of viewers around the globe. The images of mothers with children evoke collective cultural memories and archetypes often associated with motherly protection. They combine the tropes of a universal Mother Earth and the Orthodox image of Theotokos (Mother of God), a biblical metaphor of sacrifice. They also indirectly represent trauma.

These allusions are not accidental or new. The metaphor of motherhood as both the epitome of suffering and vulnerability has a long history in Soviet and post-Soviet art. Some of the first images of motherhood associated with trauma, referring to the Virgin Mary, emerged as a response to the Civil War in Russia and Ukraine in 1918-1923 (for example, Kuz'ma Petrov-Vodkin, 1918 god v Petrograde or Petrogradskaia Madonna) and then as a response to the Second World War in the artworks of veterans and survivors (for example, Mikhail Savitski, Madona Birkenau, 1978; Partyzanskaia madona, 1967 and Partyzanskaia madona, Minskaia, 1978). These paintings depict mothers with babies and allude to icons of the Mother of God.

After the Chornobyl disaster of 1986, the most devastating anthropogenic catastrophe in Europe to date, similar depictions reappeared in the art of the witnesses to the tragedy. In many artworks, the destruction caused by invisible radiation and its subsequent trauma were again directly and indirectly explored through depictions of the maternal (for example, Mikhail Savitski, Charnobyl'skaia madona, 1989; Iurii Nikitin, Vzryv, 1998; Ivan Zhupan, Chornobyl's'ka madonna (Apokalipsys), 1996; Hauryla Vashchanka, Charnobyl'ski rekviem, 1998; Taras Polataiko, Cradle, 1995). During traumatic events, we keep returning to representations of the maternal or manifestations of motherly protection, which is often colored by childhood fears that such protection will inevitably fade.

As someone who was affected by the Chornobyl disaster personally and experienced the associated trauma, I always knew that it would stay with me forever. But I am also a historian. It was essential for me to investigate post-Chornobyl art and its meaning because the recurring metaphors of motherhood called for explanation. I explained these images in my article “Memory, Trauma, and the Maternal: Post-Apocalyptic View of the Chernobyl/Chornobyl/CharnobylNuclear Disaster” and based my analysis on Griselda Pollock and Braha Ettinger’s psychoanalyses of trauma, in which they link images of the maternal to birth and mortality.

I approached images of Chornobyl trauma from the position of a cultural historian who explains the past. At the time, I could not imagine that this trope would reappear as an image of trauma, this time in the context of the brutality of the war happening in the land of my maternal ancestors when the Russian Federation invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

The first shelling and bombing attacks of peaceful Ukrainian cities shocked the world. Reflections on war and on traumatic experiences emerged immediately. Again, they were delivered through the message of the maternal. A photograph of a woman breastfeeding her newborn baby in the Kyiv subway, taken by a journalist on February 25, 2022, became one of the first poignant images of trauma conveyed through the maternal. It later inspired the creation of a painting by Marina Solomennikova, and then an icon inspired by this work and painted by Vyacheslav Okun called Kyiv Madonna was created. This icon is now located in a church in Naples, Italy.

The whole world saw the heartbreaking photographs of women with babies in underground shelters and pregnant women evacuated from the Mariupol’ maternity hospital shelled by the Russians. Another woman, who saved her baby girl by shielding her from shelling, was called the Ukrainian Madonna by international media. Another photograph, this time of a wounded woman breastfeeding her baby, became a further visual message of tragedy and an eloquent expression of trauma. Shared by millions of users on social networks, these expressive images of trauma resonated with numerous viewers.

Of course, images of war and trauma are not limited to portrayals of motherhood. The trope of suffering and motherly protection that alludes to Theotokos and Mother Earth is just one of many expressions of tragic encounters with the war. Mothers with babies appear alongside numerous images of devastating bombing, fire, and destruction of peaceful cities; graves, naked bodies of dead people, refugees, abandoned children, and many more.

Women-warriors as both the personification of Ukraine and motherhood emerged when many women joined the fight as soldiers. These portrayals always express the idea of protection rather than fighting, which is read by the viewers as subconscious protection from trauma and emotional reconciliation—mothers do fight for their children, but they also nurture, heal, and protect them.

We live in an “age of trauma” in which ecological crises and natural disasters, mass migrations and refugee crises, and post-colonialism create collective traumatic experiences. Russia's aggression against Ukraine creates new collective memories of trauma. The visual arts help us better understand ourselves and our traumas and to rebound from them. That is why, excavated from the subconscious, the pictorial language of trauma is a universal language of cultural archetypes, understood by many. Recurring images of motherhood express the prominence of motherly protection and vulnerability, sorrow and sacrifice, the temporality of being, and the fragility of life.