Nam Hye Hyun is a Professor of Russian Language and Literature at Yonsei University in Seoul, Korea, specializing in morphosyntax and semantics, with additional research interests in sociolinguistics and digital linguistics.

Kapitolina Fedorova is a Professor of Russian Studies at Tallinn University School of Humanities with research interests in sociolinguistics, language contacts, border and migration studies, linguistic landscape studies, and interethnic communication.

This post derives from an eponymous 2023 article published in The Journal of Eurasian Studies.

Introduction

Language attitudes and stereotypes significantly influence social interactions, reflecting perceptions of linguistic abilities and social meanings. Despite Russia's historical multilingualism, it predominantly embraces a monolingual language ideology, marginalizing minority and migrant languages.

Officially, Russian language policy supports the equality of all native ethnic languages. Recently, however, ethnic and linguistic diversity has been perceived as a potential threat to the nation's unity. Language purism within this ideology treats any non-standard variants as corrupt, resulting in negative attitudes toward ethnic minorities and migrants.

In the article on which this post is based, we aimed to study the prevailing language ideology in modern Russia by analyzing attitudes towards non-Russian languages in both state and public discourse. We first discussed Russia's current official language policy, then used social media studies to explore collective attitudes toward non-Russian languages. By summarizing findings from these various studies, we sought to present a comprehensive view of modern Russian language policy trends and their impact on linguistic diversity and attitudes.

Language Ideologies and the Politics of Difference

Language ideologies can include essentialist and relativist perspectives. Essentialists prioritize preserving a "perfect language" tied to national identity, valuing standard languages over variations, while relativists embrace linguistic diversity, treating all language forms as socially nuanced. Monolingualism often aligns with essentialist purism, viewing linguistic diversity as a potential threat to national unity.

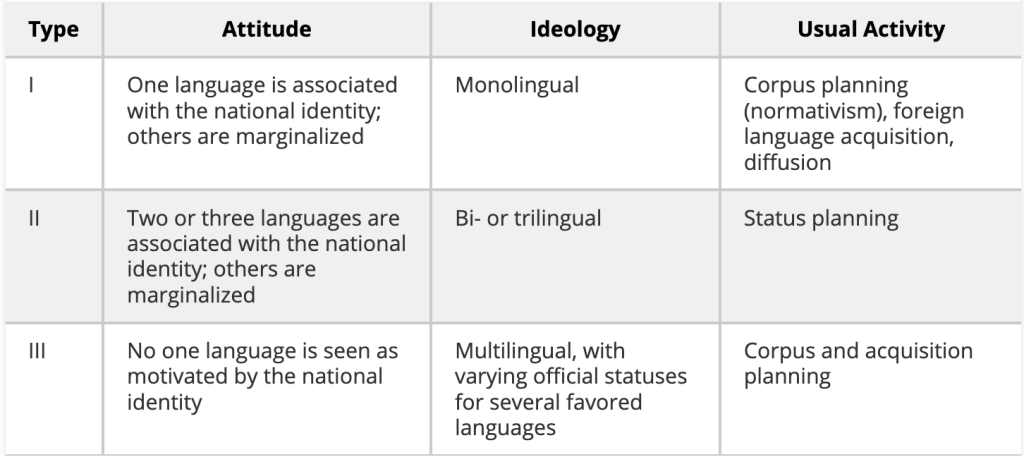

Language ideologies tend to reflect the interests of dominant communities, producing discrimination against underprivileged groups. Monolingualism and standard language ideology justify language-based discrimination, leading to underrepresentation in societal roles and inadequate linguistic support in educational and official domains. State language policy encompasses status, corpus, acquisition planning, regulating legal roles, language codification efforts, and language teaching and learning.

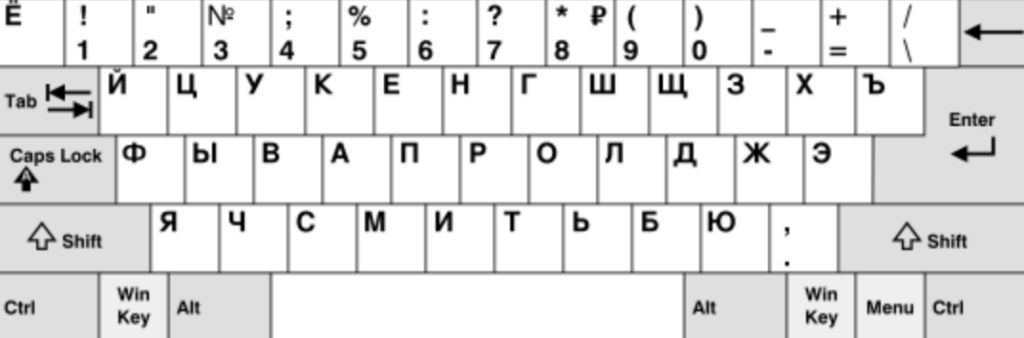

Broader ideological contexts influence all measures. In his 2004 study Language Policy, the linguist Bernard Spolsky categorizes countries' language ideologies into three types: monolingual; bi- or trilingual; and multilingual. Russia belongs to the first type, declaring only Russian as the state language and a core aspect of national identity.

Public discourse is inevitably influenced by both state discourse and state policy, but, at the same time, is capable of challenging them. In public discourse, a distinction between insiders (ethnic minorities loyal to their languages) and outsiders (Russian-speaking majority) is crucial, reflecting tensions between linguistic groups. This discourse varies in influence across governance models, with democratic societies providing more space for public discourse that would contest official policy. Separately analyzing Russian state and public discourses around non-Russian languages reveals evolving trends and differences, highlighting the impact of authoritarian tendencies on state policy as well as societal attitudes toward linguistic diversity.

Throughout Russian history, language policies have oscillated between rigid conservatism and more inclusive approaches. The October Revolution in 1917 ushered in a brief period of radical change, which soon gave way to the social, political, and cultural conservatism in the Stalinist 1930s. The post-Soviet era, meanwhile, initially embraced linguistic diversity, but later shifted towards monolingualism, particularly during Vladimir Putin's first presidency (2000-2004). This reversal is evident in changes to state discourse regarding language policy and includes issues of status, corpus, and acquisition planning, which we discuss in the section that follows.

Status, Corpus, and Acquisition Planning

In the 1990s, Russian language policies tended toward liberalism. The Law on the Languages of the Peoples of the RSFSR, adopted in October 1991, promoted regional multilingualism. However, in 2005, the Law on the State Language of the Russian Federation reinforced Russian as the sole national language and introduced the Russian Language federal program to promote and protect it.

Legal changes like these, along with official declarations, reflect a growing push for language purism. Some prominent and well-established linguists, like the rector of St. Petersburg State University, Lyudmila Verbitskaya, were even involved in campaigns to promote “correct language.” The 2005 law had already awarded the Russian language with exclusive rights, but a 2023 amendment to it prohibited public use of non-standard and foreign words. Subsequent legislation mandated using only officially sanctioned words and constructions, banning foreign loan words unless there also exists a Russian synonym.

Education reforms in Russia, too, have shifted towards monolingualism. For instance, as of 2018, students were permitted to opt out of learning non-Russian languages. The Unified State Exam, conducted solely in Russian since 2009, further solidified Russian-language dominance, disadvantaging non-native speakers and regional languages. This monolingual stance in state language policy affected foreign workers from the former Soviet Union by requiring proficiency in Russian for work permits or temporary residence permits. In sum, Russia's language policy now explicitly promotes a strongly monolingual, Russian-speaking majority.

Language Attitudes in Russian Public Discourse

Our article in The Journal of Eurasian Studies, linked at the top of the post, summarized findings from several studies on public metalinguistic discourse conducted between 2020 and 2022 in order to examine its alignment with the Russian state's official policy and ideology.

We found that, in public discourse, normative and monolingual perspectives predominate. Russian speakers commonly express negative feelings toward other languages in public settings, demand the assimilation of newcomers, prefer to ignore ethnic minority languages, and exhibit low tolerance for perceived linguistic deviations. However, this discourse is not homogeneous. Speakers of other languages actively contribute to Russian-related conversations, while issues related to the languages of indigenous peoples of the Russian Federation attract almost no attention from Russians. Both the ethnic majority and minority representatives engage in grassroots language policy and the production of a new narratives surrounding minority languages.

Despite shared monolingual and purist attitudes, diverse voices end up contributing to the public scene. Migrants increasingly participate in public discourse, challenging stereotypes about their language abilities. Furthermore, not all native Russian speakers exhibit uniform linguistic intolerance. There are advocates for multilingualism and variation, including professional linguists, human rights activists, and cosmopolitan intellectuals.

Russian language practices are diversifying, challenging monolingualism and purism. Even as state discourse aims to control all speech and suppresses diversity to enforce norms, public discourse reflects more diverse voices and seems to point toward more flexible approaches to language. The future will show which trend ultimately prevails.