Anton Shirikov is a PhD Candidate in Political Science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He previously worked as a journalist and editor in various Russian independent media.

In October 2021, the Norwegian Nobel Committee decided to award the Nobel Peace Prize to a Russian journalist—the editor of Novaya Gazeta Dmitry Muratov. Some criticized this decision on the grounds that there were more deserving candidates, such as the jailed opposition leader Alexei Navalny. Others praised the committee for recognizing the selfless efforts and sacrifices of investigative journalists who bravely do their work in authoritarian countries. Navalny himself congratulated Muratov, saying that "the main thing that we need now and always is journalism that is not afraid to tell the truth."

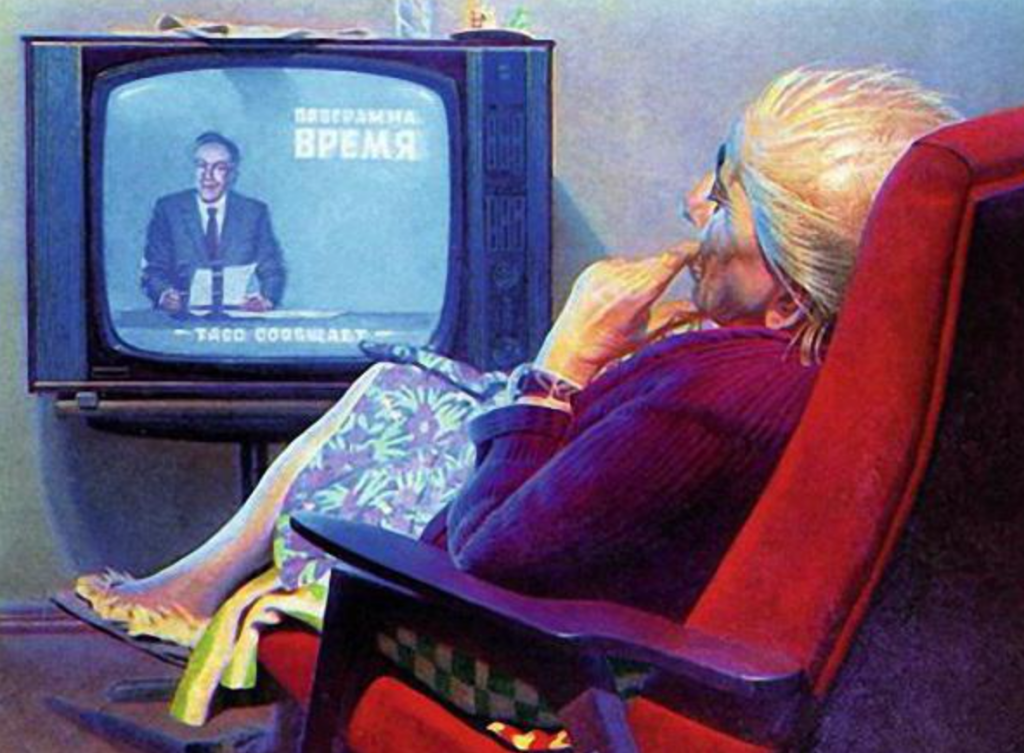

There is, however, one other problem that this debate failed to acknowledge. In countries like Russia, independent journalists are marginalized not only by governments who prosecute them but also by citizens. Most Russians do not care about the truths reported by Novaya Gazeta, Meduza, Rain, and other independent news organizations; neither can they be bothered by the Kremlin's attempts to silence these media for good. Rather, many citizens seem to be satisfied with their mainstream media, most of which are controlled by the state. More than 60 percent of Russians continue learning their news from television, which is the Kremlin's main propaganda vehicle, and about half of the respondents say that television is the most trustworthy source.

Such willingness to stick with state-run media is astounding given the flood of lies and half-truths spread by these news outlets. A typical TV broadcast is a glimpse into an alternate reality, in which Russia is the greatest country in the world, a moral and just society amidst chaos and depravity that come from the West. Russia's leader, Vladimir Putin, is portrayed in these broadcasts as a superhero who alone stands against the forces of darkness (mainly the U.S.) and yet still finds the time to reprimand lazy bureaucrats at home and to solve the problems of ordinary Russians. State media, however, would never tell you about corruption, the enormous riches of government officials, the murders of Kremlin's critics, the massive election fraud, or the country's dwindling economic fortunes.

How can Russians be okay with this web of propaganda? And why do they have so little interest in more independent and honest media? The experiments and surveys that I have conducted in the past few years suggest some answers.

The inspiration for my studies was the growing research on partisan biases, which suggested that political identities can lead citizens to strongly disagree about seemingly objective things—e.g., inflation or inauguration crowds. What if, I thought, such partisan reasoning is also at play in Russia? Maybe if you support Putin's regime, this creates a filter in your mind that distorts your understanding of media and makes you blind to the bias of propaganda.

To test this idea, I conducted an experiment, in which I asked Russians to read several news stories and to tell me whether the stories were true. The trick was that some respondents saw the stories as if they were published by Channel One, Russia-24, or other state-controlled news outlets, whereas others saw the same stories attributed to one of the independent outlets, such as Rain or Meduza. In this way, citizens' responses about the truthfulness of news stories would reflect how much they trust the respective news sources. (The study with the full description of my method and results is here.)

The experiment confirmed my expectations: Russians who approved of Vladimir Putin were more likely to believe news stories when they thought these stories were coming from one of the state-run news outlets. However, Putin supporters expressed disbelief when the same stories (supposedly) came from independent media.

In another survey, I asked Russians what they think about various state-run and independent media outlets, and the results were quite telling. Among those who strongly disapprove of Putin, almost all said that state-run TV stations such as Channel One often report false news and censor information, and that the reporting of these media is manipulated by the authorities. However, among strong Putin supporters, only a quarter admitted that state-run media lie, and only about half acknowledged that their coverage is dictated by the Kremlin. Thus, political attachments not only change what you find trustworthy—they can make you deny things that should be pretty obvious.

Such "partisanship" is not the only reason for the popularity of state media. It is easier and more fun to turn the TV on than to look for independent news outlets online. But availability or entertainment options are not enough to make the public trust the media. Such trust, even if it is limited, is rooted in the ability of state media to tell Russians what they like to hear, to support their existing political beliefs.

I am not saying, of course, that Putin supporters take every bit of propaganda at face value—people are not stupid, after all. But if you find state media more or less credible in general, you would not challenge, for example, their falsehoods about Ukraine or the West, you would be less likely to ponder on corruption, electoral fraud, or other censored issues, and there would be little sense for you to seek alternative viewpoints.

In the light of my findings, the recent attacks by the Kremlin on the remaining independent media appear not only cruel, but illogical: Russians who follow these media would not believe the regime's propaganda anyway, and the rest of the public does not care much about investigative journalism. Such a dramatic crackdown may suggest that the Kremlin is extremely concerned about its slowly declining public support, and that no amount of paranoia seems excessive in this fight.

In the Cold War era, many in the West believed that if the citizens of the Eastern Bloc could gain access to alternative news sources, the lies of propaganda would come to light, and support for communist regimes would crumble. As the Nobel Peace Prize story suggests, such beliefs are still alive today. But maybe it is time to reevaluate these ideas. Independent media are important, and we absolutely should celebrate the bravery of journalists who continue to do their work even when it might cost them their job, their health, or their lives. But their work is, sadly, not enough to counter authoritarian propaganda and disinformation. Ultimately, it seems, discovering the lie at the heart of the Kremlin's propaganda is up to citizens themselves.