Jill Martiniuk is a Visiting Instructor-Digital Teaching Fellow at the University of South Florida.

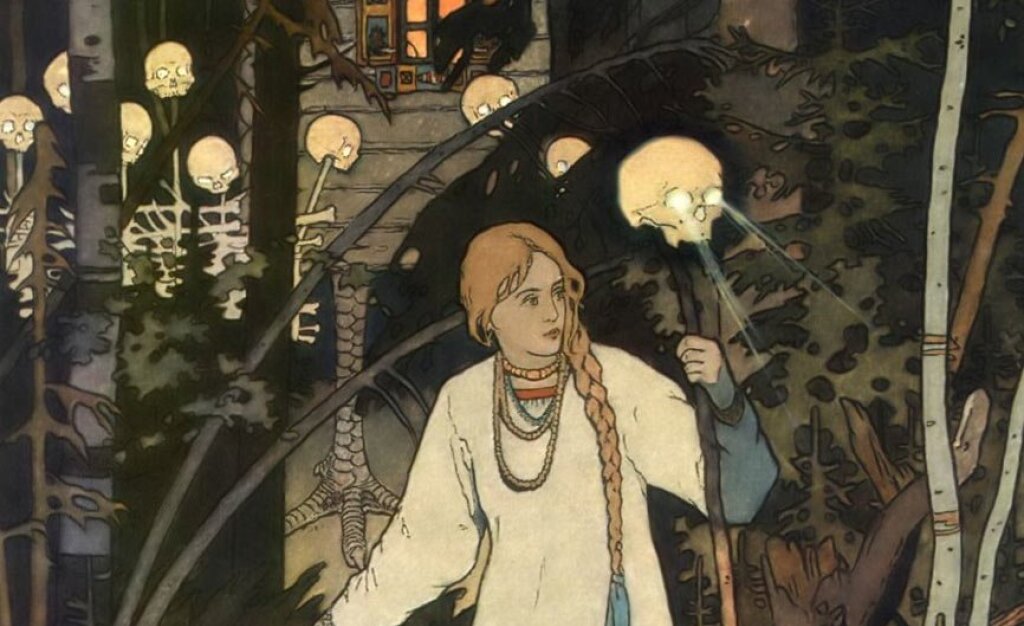

Russia's politics and culture have long captivated the attention of writers and artists living beyond her borders. The mystique and allure of images like bejeweled eggs, lost Tsarinas, and witches who live in houses on chicken legs has led to the appearance of Russian-inspired popular media in the West, including Fox Century’s 1997 animated film turned Broadway musical Anastasia and the popular FX spy drama The Americans.

Recently, Russia — or, at least, an imaginary version thereof — has become a standby among writers of American young adult and popular literature. In the past decade, both markets have demonstrated an interest in Slavic folklore, with offerings in that vein well-received by readers and critics alike. However, rarely is Russia mentioned by name in these works. Instead, texts use the characters, symbols, and motifs from Slavic folklore, often without context, to create an imagined version of Russia, albeit one that still allows the reader to identify the setting as vaguely "Slavic." With their world-building privileging their own understanding of Russian culture, these Western writers have created spaces that both resemble and depart from Russia as an existing cultural and geographical entity.

The Young Adult Market

Those who have not recently been in a physical bookstore may not be aware of the scope of the contemporary young adult market and its impact on sales and publishing decisions. While the genre is labeled “young adult,” a 2012 study by Bowker Research found that over 55% of readers of the genre were 18 years or older, with 78% of respondents reporting that the purchase was for themselves rather than a younger reader.

Though there were books marketed to children and teenagers in the earlier twentieth century, including classics like C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia and L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables, the genre exploded in the 1990s and early 2000s with the publication of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, followed quickly by Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games and Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight. In those two decades, the YA market saw a 40% increase in sales while adult market sales declined by almost the same percentage. These trends have spurred some publishers to triple their YA titles.

The folkloric motifs now found in popular and young adult literature are not limited to those of Russian origin. Recently, both markets have shown an affinity for high fantasy and folklore, with plots unfurling in alternate pasts or fantasy worlds that draw heavily on a variety of cultures. Recent works borrow from the folkloric traditions of India (S.A. Chakraborty’s Kingdom of Copper); Kashmir (Sabaa Tahir’s An Ember in the Ashes); West Africa (Tomi Adeyemi’s Children of Blood and Bone); and Argentina (Romina Garber’s 2020 Lobizona). Yet despite this diversity of sources, Russia occupies a special place in today's YA landscape, to the point that several media outlets — Russian Life, Barnes and Noble, the Young Adult Library Services Association, and the Seattle Public Library — have published dedicated pieces or listicles on the topic.

Contemporary Works Featuring Slavic Folklore

Today's young-adult and popular fiction frequently uses Slavic folklore as a theme or world-building foundation. Recent examples ones include Catherynne M. Valente's Deathless (2011), Emily A. Duncan’s Wicked Saints (2019) and its sequel Ruthless Gods (2020), Naomi Novik’s Uprooted (2015) and Spinning Silver (2018), Katherine Arden’s Winternight Trilogy (2017-2019), and Leigh Bardugo’s Grisha series (2012-2014). The popularity and literary quality of these and other books based on Slavic folklore vary, but some have found a market even beyond young adult readers. Bardugo’s Grisha was recently optioned for a TV series by Netflix, while Novik’s Uprooted was bought by Warner Brothers after a three-studio bidding war for the rights.

The key folkloric elements of these works are remarkably similar. Each features a young female protagonist with special abilities rooted in Russian folkloric or pagan beliefs. Each is set in a country at war with itself or a neighboring country. The young woman often finds herself charged with saving the country from destruction at the hands of some evil force. In accordance with what Vladimir Propp would have called the standard "morphology" of folkloric narrative, the protagonist often embarks on a hero’s journey to seek a specific person, object, or place that will offer her sufficient power or status to overcome the problem.

How Do Readers Recognize These Works as Russian Inspired?

While numerous studies have addressed Russians' views of American culture, less work has been done on the opposite set of perceptions. Works like Warren Walsh’s “What the American People Think of Russia” (1944) and the more modern America Through Russian Eyes: 1874-1926 (1988) by Olga Hasty and Susanne Fusso tend to focus on politics or current affairs, without considering how or why American authors write about Russia.

Is the "Russian" content of recent young-adult titles legible as such to the lay audience? Shoppers selecting these books are not typically seeking Russian literature per se. When the average American reader picks up a book by Dostoevsky or Tolstoy, the text's Russianness is clear from the author's name and reputation. Meanwhile, Russophone readers would likely find the names, characters, and symbols in these contemporary young adult works to be clearly influenced by Russian language and culture. For example, no Russian speaker would find it mysterious that Emily Duncan’s protagonist in Wicked Saints, Nadezhda, is usually called "Nadya." But how does the same shift read to an American audience? How is the stories’ Russianness coded into the text when Russia is not directly mentioned? How do readers interpret that Russianness when narratives are set in places named Ravka, Kalyazi, and Tranavia?

In fact, many people do read these works as Russian-inspired or at least connect them to Russian culture. We know this because, unlike literature targeting older audiences, young adult literature typically has a massive digital footprint. Online fandoms (including wikis), social-media-based book review platforms like GoodReads, and forums set up by authors' teams offer insight into the ways readers connect to the Russian content of these narratives. For example, both Leigh Bardugo’s website and the accompanying fandom site Grishaverse, make clear that readers recognize an "otherness" to some of the vocabulary in her series. On the website Bardugo dedicates to the series, there are several pages discussing the Ravkan language. On the Tongue Twister page, Bardugo speaks to the connection between the language of her imagined country and Russian:

Ravka isn’t Russia, so it didn’t make sense to simply transcribe Russian (though it would have made life easier). And even if I had, for non-speakers, Russian is an incredibly opaque language. Because we don’t share an alphabet, very few words have any resonance for a western reader. Still, the world of Shadow and Bone was clearly inspired by Russia and I didn’t want to violate the reader’s sense of place by throwing some random language into the text. My goal was to use language to reinforce the reader’s experience of the world rather than undermine it. (Tongue Twisters, n.d.)

Bardugo establishes the connection between Ravka and Russia for her reader through her website, which also includes a slideshow of images from Russian folklore that she says inspired the series.

Fan generated wiki pages like the Grishaverse shed further light on the connection between the series and Russian folk culture. In the comment section of the Grishaverse wiki, users interact with one another by posting questions and responses. One user asks, “Is Ravka a real place?" and receives the response, "No, but it is heavily influenced by Russia" (Ravka, n.d.) Other users reiterate the Russian influence on the novels' setting throughout the comment section, sparking the connection for users who may not be familiar with Russian folk culture.

Conclusion

Although the contemporary American young adult writers who set their stories in Russia or Russian-inspired lands vary in their approaches, they share some traits in common in how they imagine Russian culture. These common features enable readers of these works to make connections not only among these young-adult works, but also to Slavic folklore itself.

To the young adult writers profiled here, Russia represents an unknown—one they can reimagine or create to suit their storylines. This set of choices, while lucrative, is not unproblematic. How can these writers, some of whom have never been to Russia, do justice to anything like "authentic" "Russianness" (assuming such a thing exists)? This question will likely recur as the young adult genre continues to grow.