This is the fourteenth, entry of Russia’s Alien Nations: The Secret Identities of Post-Socialism, an ongoing feature on All the Russias, and also the first entry of Chapter 1. It can also be found at russiasaliennations.org. You can also find all the previous entries here.

Chapter 1:

Soviet Self-Hatred:

The Rise and Fall off the Sovok

Very Nice!

Still not quite two decades old, the twenty-first century has proven itself a huge disappointment, at least from the point of view of prognostication. By now, according to a plethora of utopian schemes dating back to the nineteenth century, the world was supposed to be united, even homogenous. Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward casually predicted global unity, an assumption later confirmed in nearly every single popular science fictional representation of earth’s future. Socialists of all stripes disdained the nation state and the empire when the twentieth century began, only to throw themselves wholeheartedly into the pointless slaughter of World War One. The United Nations gave hints of a future unity that would erase the failure of the League of Nations from memory. Space flights provided external photographs of the planet earth (the “big blue marble”) that inspired a sense of common destiny. Rock stars sang “We Are the World,” Francis Fukuyama predicted the end of history, and game theory made local knowledge look quaint.

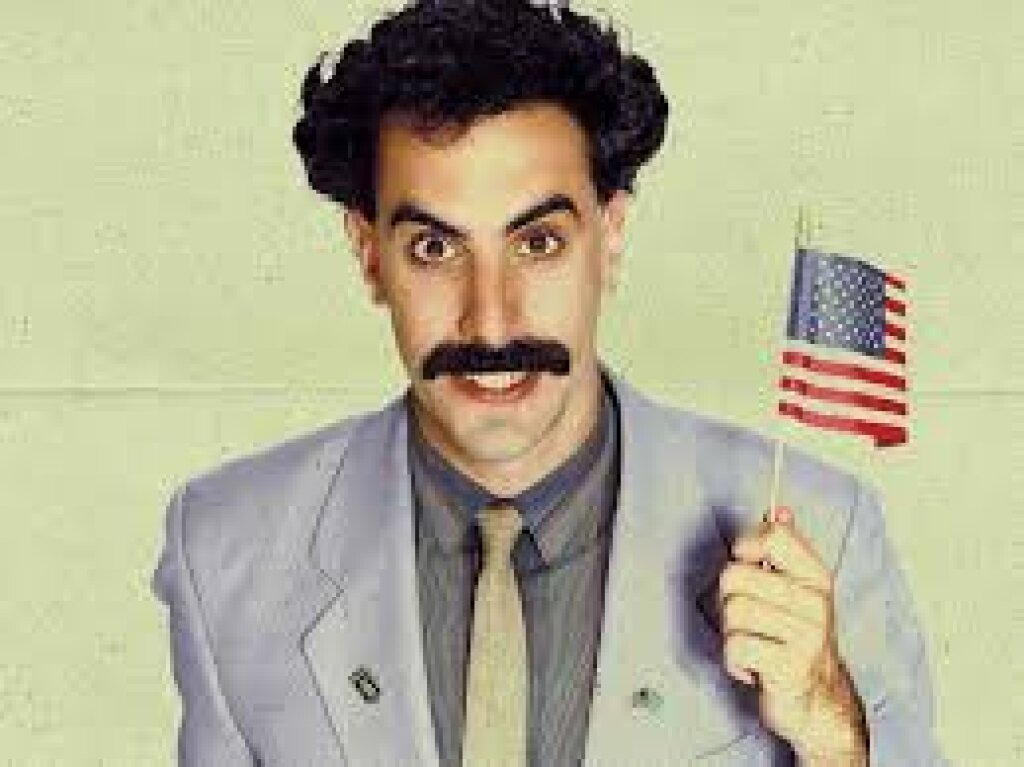

To see just how the local has taken its revenge (and to get a hint as to what this might have to do with the former Soviet Union), we need look no further than the embarrassing yokel who conquered the entertainment world: Borat Sagdiyev. Created by Sacha Baron Cohen in the mid-1990s, the Borat character was featured on his Da Ali G Show (1999-2004), before spinning off into his own movie, Borat: Cultural Learnings of American to Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2006). Based on a doctor Baron Cohen met while vacationing in Astrakhan (a phrase that sounds as unlikely as anything else to come out of the British comedian’s mouth). Borat is supposed to be a journalist from Kazakhstan traveling in Britain (and, eventually, the U.S.) in order to report to his audience back home.

Americans lined up to see the film, which was number one at the box office during its first weekend. Kazakhstan's government had to tone down its initial outrage at the Central Asian nation's portrayal as the homeland of joyfully clueless urine-drinking, Jew-hating, sister-shtupping rapists. The film board of the Russian Federation recommended against the movie's distribution on Russian territory, citing the potential for inciting nationalist hatred. And, inevitably, Baron Cohen and his studio were threatened with lawsuits from a veritable rainbow coalition of offended parties: American frat boys, New York feminists, Romanian Roma, and, at least at first, the aforementioned government of Kazakhstan. Such strange international bedfellows provide a glimpse of Borat's globalist scope, uniting disparate cultures through his brash violation of the norms of multicultural etiquette, thereby, ironically enough, bringing his enemies together in an angry and offended variation on “It’s a Small World After All.”

For Americans, Borat is a familiar type, the usually (but not always) Second World yokel who has been a figure of fun since the days of the Cold War. Steve Martin’s and Dan Ackroyd’s crass, Czechoslovakian “Wild and Crazy Guys” from Saturday Night Live in the 1970s, the linguistically-challenged narrator of Jonathan Safran Foer’s relentlessly annoying Everything Is Illuminated (later portrayed by Liev Schreiber in the film of the same name), the hapless refugee in Stephen Spielberg's Terminal, the hopelessly backward natives of mud-ravaged Elbonia in the comic strip Dilbert, and the pornography-loving adolescent on That 70s Show, whose unpronounceable name is replaced by the acronym "Fez" for "foreign exchange student" (though we do learn that the first five k's in his last name are silent). Combining good-hearted buffoonery with the slightest threat of aggression, the yokel is almost always male (the women from their countries usually portrayed as peasant mothers, shrews, and whores from central casting). Most of these yokels fit a particular type: they are sexually preoccupied, prone to ostensibly hilarious malopropisms, and strangely lovable despite (or perhaps because of) their utter inappropriateness. Suddenly, the title of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward takes on a whole new meaning.

None of this is, of course, Russian or from Russia, but let me point out how quickly Slavists accepted this material as their own: in 2008, Slavic Review came out with a special cluster on Borat (including my own article, on which the text you are reading heavily draws), and Robert A. Saunders, a political scientist specializing in Russian and Central Asia, published a monograph the following year, entitled The Many Face of Sacha Baron Cohen: Politics, Parody, and the Battle over Borat. More than a decade later, and long after Baron Cohen largely discontinued the character in favor of offending other, more provocative countries, Borat still haunts the region, with Kazakh athletes at international sporting events continuing to be humiliated when, instead of their country’s actual national anthem, their hosts play, “O, Kazakhstan,” the song penned by Baron Cohen for the end credits of the movie (“Kazakhstan, Kazakhstan, you very nice place / From plains of Tarashek to northern fence of Jewtown / Come grasp mighty penis of our leader / From junction with the testes to tip of its face!”)

Borat resonates because, despite Baron Cohen’s presumably limited knowledge of the former Soviet Union and complete mischaracterization of Kazakhstan, Borat exemplifies a particular kind of Soviet and post-Soviet shame usually designated by the word “sovok": the sense that the (former) country, which once prided itself on its modernity and a utopian ideal of internationalism, had degenerated into a nest of embarrassing yokels. Borat is the ex-Soviet idiot abroad, the embarrassing reminder of Old Country backwardness, an unassimilable alien. One of the telltale moments in the film comes when Borat's southern dinner party hostess optimistically assesses the faux Kazakh's potential: "You could be Americanized someday." Two minutes later, Borat returns from the bathroom with a plastic bag containing his own feces Where can I put it, he asks her, in an exchange that is truly emblematic. With his body and its unsightly products, Borat has issued her a challenge: assimilate that!

As a figure in popular culture, the yokel is a reminder of everything the cosmopolitan wishes to leave behind: the painfully ethnic, localized, and uncivilized set of customs that used to define him, and that unsympathetic onlookers can still deploy against him at will. Despite the fact that the postwar Stalinist anti-Jewish campaign turned “cosmopolitan” into a dirty word, the citizens of the Soviet Union were supposed to represent the best of the multinational cross-fertilization that modernity facilitated. The Soviet or post-Soviet yokel turned an optimistic anthropological imagination into a site of degeneration.

Next: It’s Raining New Men